How Thinking in a Foreign Language Reduces Superstitious Belief

Superstition is everywhere in our modern lives. Each Friday the 13th, nearly a billion dollars in business is avoided because people are afraid that it will be bad luck to do it that day. In the United Kingdom, traffic accidents increase dramatically on the same day, despite less traffic overall. Even for those of us who consider ourselves rational people, the effects of superstition can still hinder us. We know we have nothing to fear, but fear it anyway.

A new study shows us a way to bypass that part of our mind that worries about black cats and broken mirrors: speak in another language.

In one part of the study, Italian volunteers who were proficient in the German or English languages were asked to read about an event associated with bad luck, such as a breaking a mirror or walking under a ladder. They were then asked to rate how the event in the story made them feel, and how strongly it affected them.

While the scenario invoked negative feelings in nearly all of the subjects, the ones who read it in a foreign language noted a reduced level of negative feeling compared to those who read it in their native tongue.

The study was repeated with other languages to see if the effect also existed for events with a positive connotation, such as finding a four-leaf clover. Similar results were found, with the same reduction in the intensity of mood changes for those who read it in a foreign language. The effect held for all demographics studied, and the authors took steps to assure the readers would not misunderstand the texts and give false positives.

This study suggests that tendencies to “magical thinking” can be reduced by presenting and processing information in a second language. While it does not remove these tendencies, as the subjects still showed both positive and negative responses to certain phenomena, it was starkly reduced in every case. It supports the findings of previous studies that suggest memories are partly tied to the language they are made in, and adds evidence to the hypothesis that the part of the brain that processes information in a second language is more rational than the part that works in our native language.

Weird. What else happens to me if I do my thinking in a foreign language?

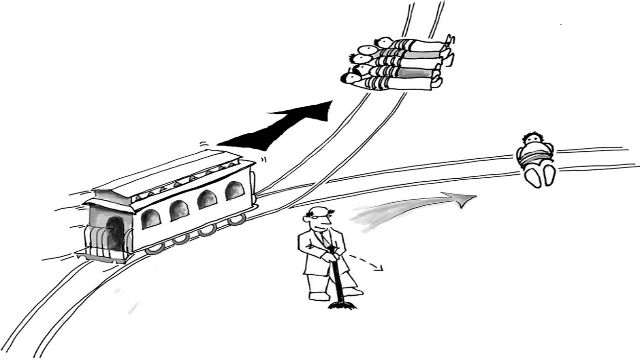

The authors of this study point out that other research has shown that people will make different choices when speaking a second language than when speaking in their native tongue. They are more willing to sacrifice a stranger to save five other people, will spend more time discussing embarrassing topics, are more tolerant of harmful behaviors, and more permissive of helpful behavior that has dubious motives. In all, they are more rational.

But, why would the choice of language have such an effect on behavior?

The authors of the study suggest that the part of our brains that processes our native language is more intuitive and less rational than the parts that focus on new languages. This idea, that our linguistic choices can have such an effect on our rationality, can be a little off-putting for those of us who like to suppose ourselves as rational people.

So, what can I do with this information?

The findings could have implications for language study and the neuroscience of how our brains process language. It might also be used to advantage in diplomacy and business, with negotiators selecting a language that will most benefit their rationality. It also means that next time you see a black cat crossing your path, you might do better to disregard it in a second language than try to shrug it off in your first.