She discovered Jurassic dinosaur fossils that challenged Bible-based creationism

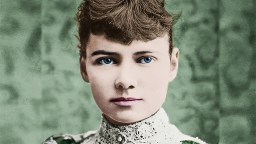

Portrait of Mary Anning. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Mary Anning was a British fossil collector, dealer, and paleontologist (before there was paleontology). Her studies challenged the Bible-based view of creation, and her gender and status challenged what a scientists should be. The fossils she found proved that there was something before man, which upset the established narrative of the history of life on Earth. The British Journal for the History of Science describes her as “the greatest fossilist the world ever knew.”

Anning would roam the limestone cliffs in Dorset, England. This is where she made many fossil discoveries, including the first ichthyosaur skeleton. This creature must have looked quite strange, its skull was four feet long and its jaw was the shape of a pair of needle-nose pliers.

Her discoveries would introduce a world of firsts to the scientific community, including the first two plesiosaur skeletons ever found, the first pterosaur skeleton located outside Germany, and fish fossils. She would collect fossils that became dislodged after mudslides and retrieve them before they were swallowed by the sea’s tides. This work could be quite dangerous. In 1833, the landslide that took her dog’s life nearly took her own.

It’s important to note that during the early 1800s, most people in Britain maintained a literal interpretation of the creation story, believing the Earth was only a few thousand years old. But these new creatures buried beneath our feet made scientists consider there may have been an entirely different world before our own.

Her fossils became the evidence of a new idea in science: extinction. French anatomist Georges Cuvier had argued this after analyzing mammoth fossils, but many explained his idea away, saying these creatures still existed somewhere else on Earth. Extinction would imply God’s creation was imperfect. However, Anning’s findings were evidence towards Cuvier’s hypothesis—that whole species have disappeared in Earth’s history.

Duria Antiquior is a watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche depicting what life could have looked like in ancient Dorset. This representation of prehistoric life was influenced by the fossils Anning found, and proceeds from the sale of the painting were donated to her efforts.

During her life, Anning received little recognition for her work. She lived in a time when women couldn’t vote or attend university. As a woman of low social status, she had trouble receiving the respect of her peers and even getting credit for her finds in the scientific community.

Lady Harriet Sivester, the widow of the former Recorder of the City of London, thought it was “divine favour” that such a young woman could posses such knowledge in the sciences, indeed, even more than “anyone else in this kingdom.”

“She says the world has used her ill … these men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal of publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages,” wrote Anna Pinney, a woman who accompanied Anning when she would go in search for fossils along the cliffs.

However, history has not forgotten Mary Anning, and we remember her legacy of field research and the impact it’s had on understanding life on our planet.

***

Big Think is proud to partner with the 92nd Street Y to bring you this series on female genius as part of its 7 Days of Genius Festival.