Does lack of exercise lead to dementia?

In 2013, the RAND Corporation decided to assign a monetary cost to dementia in the United States. The resulting study revealed that we’ve acquired a remarkable burden, paying between $157 billion to $215 billion annually, mostly by providing institutional and home-based care. The report also stated that these costs could more than double by 2040 if current trends continue.

That’s just the financial cost. For anyone who’s watched a family member or loved one battle dementia, the emotional toll is an even greater price to pay. The last time I saw my grandmother she was referring to me by my sister’s name. Soon after that, she was put in a facility; within weeks the nurses asked my family not to visit as it was too distressing—on the faculty. Calming her down after a visit was apparently too much work.

As with many incurable diseases, our elders are being sent away to die lonely and confused. This is not necessarily the family’s fault, as home care can be prohibitively expensive. Perhaps we don’t recognize that, barring a tragic accident, we too will be elders, faced with the dilemma our parents and grandparents are now confronting. This is where the whole ‘do unto others’ thing should be kicking in.

101-year-old Man Kaur from India celebrates after competing in the 100m sprint in the 100+ age category at the World Masters Games at Trusts Arena in Auckland on April 24, 2017. (Photo by Michael Bradley/AFP/Getty Images)

Yet we’re terribly short-sighted animals, focused more on immediate gratification than aging sustainably. Preventive practices may or may not help you stave off dementia; there is a certain level of faith required when it comes to realizing their potential benefit.

But there are things we do know. Recently, scientists have established links between sugar, high blood sugar levels, and alcoholism with dementia. In one way or another, all three of these studies are related to too much sugar being a primary cause of dementia.

Cutting down on sugar is one preventive measure for decreasing your risk for dementia. But there are other proactive means for improving memory skills and strengthening cognition now that also buffer against possible issues down the road. Abandon sugar, but put certain nutrients in. Learning a new language and musical instrument are powerful means for further education. Reading certainly does not hurt.

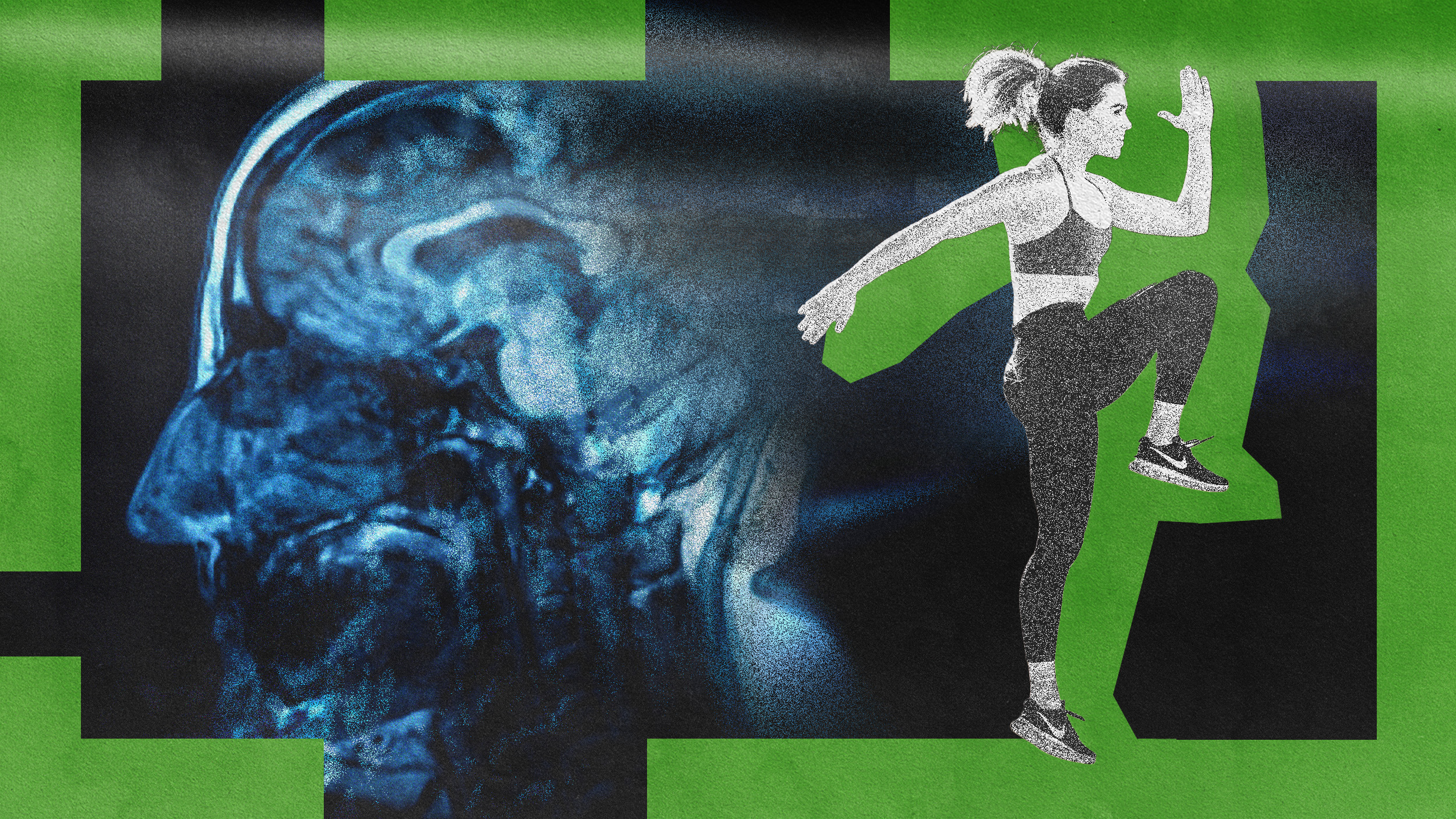

Brain training exercises have been clinically shown to reduce the risk of dementia by 30 percent. Being social helps you stay alert. Relying less on smartphone maps and orienting yourself spatially by learning various routes (as well as getting lost, on occasion) keeps your hippocampus engaged. And then, of course, there’s exercise.

Levels of the essential nutrient, choline, rise with an increased loss of nerve cells—a marker of Alzheimer’s disease. Last year, researchers at Goethe University Frankfurt had senior volunteers (aged 65-85) ride a stationary bicycle three times a week for thirty minutes over a twelve-week period; the control group did not exercise. The exercising group experienced stabilized choline levels, while the control saw an increase in this metabolite.

Another study from 2013 stresses the importance of cardiovascular exercise. Art Kramer, a neuroscientist who directs the University of Illinois’s Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, directed one group of older adults to exercise moderately for 45 minutes, three times a week. The control group ended up losing 1.5 percent of brain volume, while the exercising group increased brain volume by 2 percent. This increased volume resulted in better memory scores.

While varying levels of dementia affect over half of adults 85 and over, epidemiologist Bryan James told NPR that it’s not an inevitable aspect of aging. “It’s simply not pre-destined for all human beings. Lots of people live into their 90s and even 100s with no symptoms of dementia.”

Cardiovascular exercise has been studied on a number of occasions, but that’s not the only form that’s helpful. Besides keeping osteoporosis at bay and keeping spines and muscles strong and healthy, weight training is also beneficial for preventing dementia. One hundred Australian volunteers, all between 55 and 86 years of age, were part of a weight training study. The lifting group, which involved two workouts a week for six months, scored significantly higher than the control group, which only performed stretching exercises during that period. Unfortunately for hardcore fans of yoga, the control group experienced cognitive decline.

An elderly man practices tai chi on the frozen lake of Hou Hai in Beijing on January 23, 2018. (Photo by Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty Images)

Our body was designed by nature to engage with the environment at every stage of life. It makes sense that if we stopped moving our bodies, our brains would suffer. The successful navigation of your environment requires physical and cognitive engagement. Unfortunately, we’ve created societies that remove the physical element from our daily struggles. It would be foolish to think we wouldn’t suffer mental consequences.

In my role as a fitness instructor, I’m often asked what age people should begin various types of training. My answer is always the same: right now. I’ve watched too many people just start (or “get back in”) to a fitness routine in their fifties and sixties. While better than never, incorporating a variety of exercise formats—cardiovascular, weight training, restorative and regenerative practices like yoga, meditation, Feldenkrais, and fascia release—should be a lifelong habit. Given all we know about the myriad benefits of movement on our brains and bodies, there really is no excuse.

—

Derek Beres is the author of Whole Motion and creator of Clarity: Anxiety Reduction for Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles, he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.