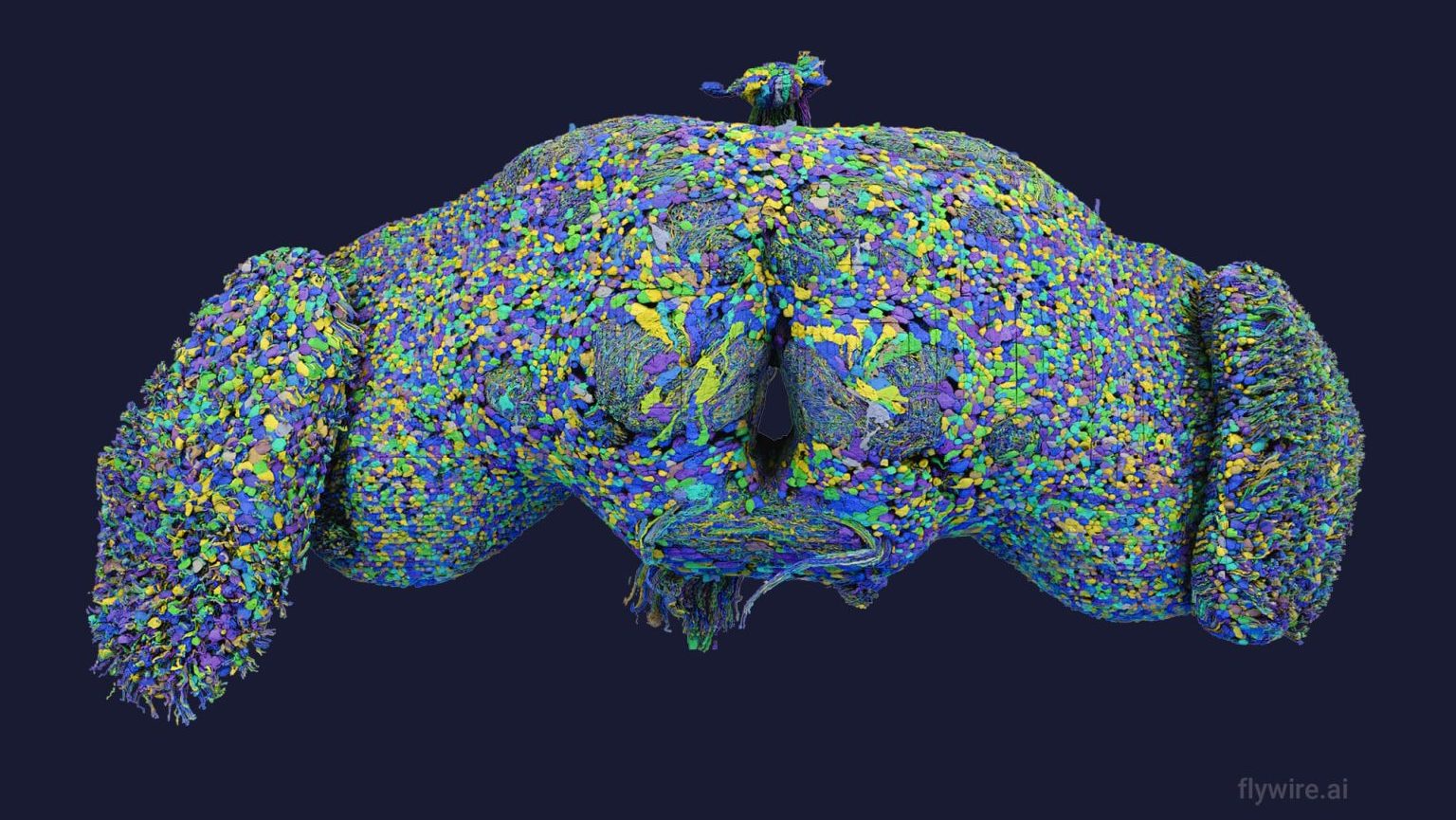

Animal studies allow neuroscientists to study the brain at the level of individual neurons, unlike human brain-imaging studies.

Question: Why study animal brains to learn more about our own brains?

Joseph LeDoux: I think that brain imaging is not a very good way to test subtle distinctions in a sense because, especially... well, if you look at what the... what you can learn from a brain image, it’s like trying to find out something about New York City by studying New York State. In other words, it’s a very big representation and there’s a lot going on within those big blobs that you see on a brain image.

And that’s why animal research is so important because we can go in and study individual cells and individual synapses on those cells, which is like, again, that’s a tiny part of New York City if you’re looking at the entire map of New York State. And so you need to be able to get to that point of resolution

Question: Can we really apply what we learn from animal brains to our own?

Joseph LeDoux: Throughout the history of psychology there’s been a struggle between what can we learn about psychological states in humans and animals, what can we learn about psychological states by studying conscious states in people and unconscious states, and so forth. There is always a struggle between animal/human, conscious/unconscious. And the behaviorists got rid of that because they said we can’t study consciousness because it’s not a objective thing that you can measure. So they said that what we should do is to just study observable behavior. So they got rid of consciousness. Then the cognitive revolution came along and brought the mind back to psychology, but it didn’t bring back the mind that the behaviorists got rid of, it brought back the mind as an information processing device.

So when I got interested in emotion in the '70s, emotion was still being thought of in terms of subjective conscious experiences, whereas other aspects of psychology, like perception and memory, were thought of as information processing functions. So you could learn a lot about the way the brain processes the redness of a sunset without actually knowing how it experiences the redness of the sunset.

But in the study of emotion, that kind of leap had not been made, and so people were still thinking of emotion as the conscious feeling of, say, of being afraid, as opposed to the information processing that goes on when you detect danger. So all animals have to be able to detect danger and respond to danger in order to stay alive, including humans. And so my approach was to say, "Well, let’s forget about consciousness, it kind of gets in the way of studying what we want to study, which is how the brain processes information about emotional situations." So I decided to study how the brain detects danger and response to danger independent of any conscious experience that the rat has or doesn’t have.

So I remain completely agnostic about whether the rat experiences fear and instead focus totally on how rats and humans detect and respond to the danger. Learn about new dangers and use that information in adaptive ways. So that leaves a big hole in terms of what we can learn in rats, but it’s been an interesting time in research. We’ve learned a lot about how the brain detects and responds to danger. We’ve put together a pretty comprehensive understanding of that whole system.

So we haven’t explained what the humanists want to know about when they talk about emotions, but we’ve learned a lot about what goes on in an emotional situation in terms of how the brain processes information.

Recorded on September 16, 2010

Interviewed by Max Miller