Imagine this: Your family doctor prescribes you a course of antibiotics for what seems like an innocuous sinus infection.

And since some antibiotics also can cause stomach issues, your doctor suggests taking probiotics to keep those side effects to a minimum. Two weeks later, your sinus infection is all cleared up, but your stomach issues continue. A week later, two weeks later, three weeks later, still no better, and you’re losing weight. Everything just goes right through you.

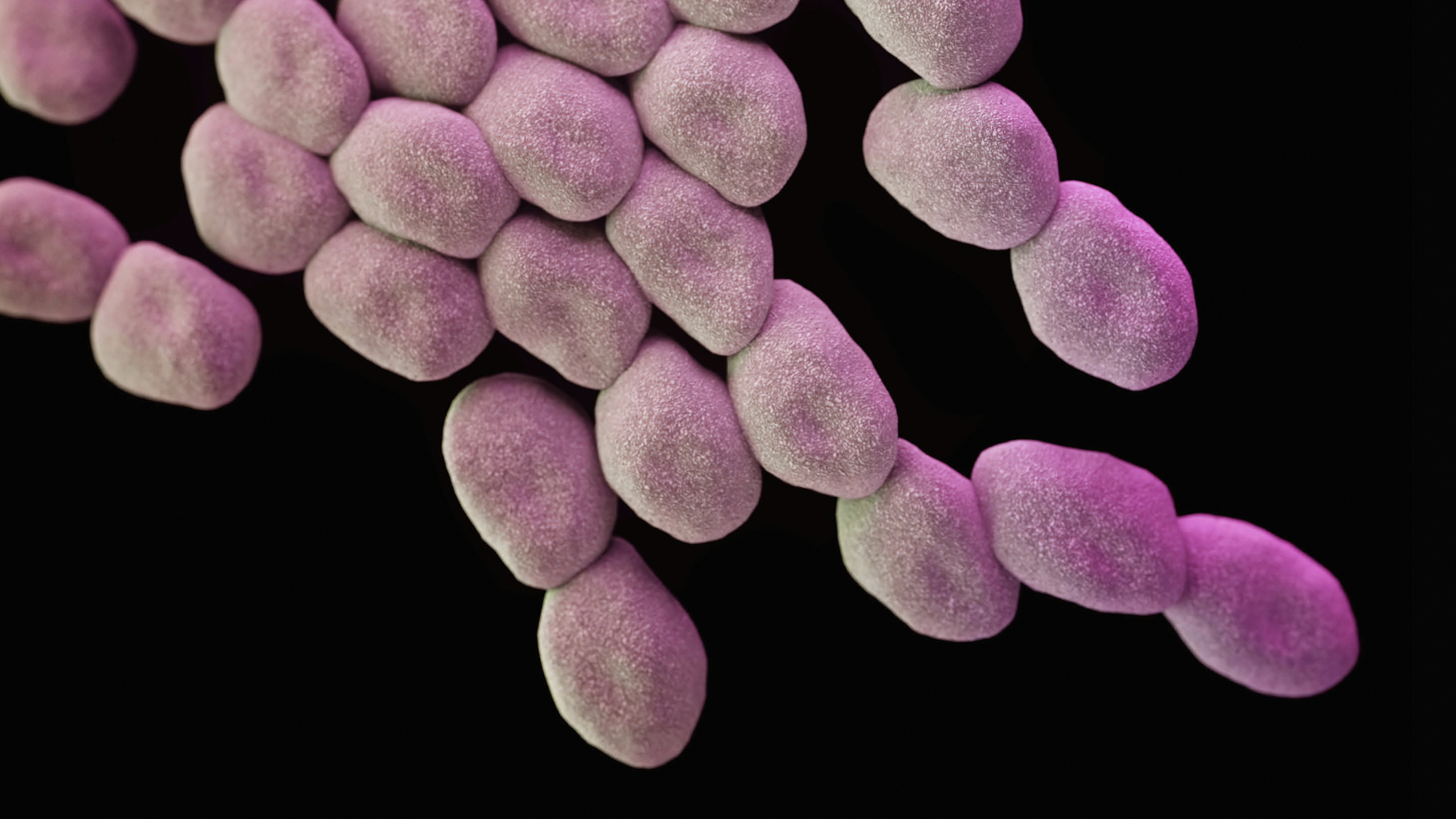

You return to your doctor only to you learn the bad news: You’ve got Clostridioides difficile, also known as C. diff, a bacterium that causes diarrhea and colitis.

C. diff affects about half a million people in the U.S. each year, and many of them—including 1 in 11 people over age 65—die from it. Treatment usually consists, ironically, of another round of a different type of antibiotic.

But in recent years, scientists have found another way to treat C. diff—through a type of microbial therapy called “fecal transplantation.” It sounds gross, but for those living with C. diff, it’s essentially a lifesaver. The procedure has about an 80 percent success rate, and has cured tens of thousands of patients.Mark Smith has been at the forefront of researching and implementing this type of treatment, partly motivated by the struggles of a family member.

Smith, who has a PhD in microbiology, has devoted much of his adult life to treating and curing C. diff, partly by founding two companies—OpenBiome and Finch Laboratories. The former is basically a non-profit “stool bank” that collects life-giving samples from donors, and the latter is a research and development company working on making the treatment available to all who need it—including in pill form.

At Finch, where Smith is CEO, the mission is “to harness the microbiome to transform human health.” ORBITER caught up with Smith to learn more about the treatment, and the hope it’s bringing to the many who live with C. diff.

ORBITER: Were you a science geek as a kid?

Mark Smith: No, not at all. I thought high school biology was boring because it seemed like it was just about memorizing a bunch of facts. I wasn’t planning to go into the sciences; my interests were primarily in environmental policy and economics. But in college I took a biology class because some friends said it was really interesting. And I totally fell in love with it. It changed my plans, and I decided to major in biology. I ended up going to MIT to get a Ph.D. in microbiology.

Let’s talk about the human microbiome. Our bodies are made up of trillions of cells, and each of those cells are a part of us. But the microbiome is made up of bacteria and organisms that live inside us. So is the microbiome part of me or not?

It’s a distinctive property of your being. Think of your metabolism, which helps determine if you’ll gain weight quickly when you eat certain foods, or it might even affect your moods. Those things depend on the microbes that live within us.

So, it’s hard to address the philosophical question about our identity. Is it our identity just a biological entity, our genome? Or are we made up of properties that are fundamentally dynamic to our bodies? In recent years, we’ve even learned that our genome is not immutable. Epigenetics can determine which genes are turned on or off, which result in heritable changes. And your microbiome can pick up new bacteria as a result of the places you visit and the food you eat, which also results in changes.

All to say, I very much think the microbiome is a big part of who I am, and it’s very dynamic and it’s something that we can change. It’s part of our identity as humans.

I understand we begin acquiring those microbes even before birth.

In the womb, we’re in almost a sterile environment. But during the birth process, we’re exposed to very many microbes, a complex milieu of bacteria and lots of other things. That begins in the birth canal, which includes healthy doses of feces. That’s not something that we usually talk about, but those feces—both from the mother and the baby—are important for feeding the infant gut with appropriate microbes.

The human gut has good and bad bacteria.

It’s such an important part of the birth process that we’ve learned that infants born via C-section miss out on a lot of those important microbes, resulting in a very different composition of the microbiome early in infancy. C-section births turn out to be associated with a lot of diseases later in life, because your immune system is essentially being trained by the bacteria you’re exposed to during early childhood.

The classical way of thinking about the immune system is that its job is identifying friend or foe. If you can’t expose it to the right microbes at the right time, that has a lot of implications for the accuracy of your immune system to determine potential threats. Specifically, your immune system becomes overly active.

Today, there’s a suite of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases that didn’t exist a hundred years ago, and these have become some of the biggest drivers of morbidity and mortality in Western society—things that are still rare in developing countries. It turns out that these are closely associated with changes in your microbiomes.

We’ve been able to drive down the incidence of a variety of infectious diseases through vaccination efforts, better public health, and the deployment of broad-spectrum antibiotics. But during the same time period, all these other diseases have cropped up, like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease. Even diseases like multiple sclerosis have become much more common that were very rare historically. Our genome hasn’t changed during that period, right? So something about the environment has.

Well, since you brought up feces . . . A big part of your company’s research is in the field of fecal transplantation. That sounds pretty gross. Please explain it.

The basic concept is that you can transfer the microbial community from a healthy individual to someone who is missing some of those key microbes. I started researching this in my PhD program, trying to figure out if the microbes were driving the disease or if they’re just associated with the disease. Fecal transplantation actually lets you test for causality. You can go in and basically re-engineer somebody’s microbiome, and see if you’re able to change their clinical phenotype. And you can do this with remarkable efficacy.

I’ve spent the last decade of my life trying to figure out how fecal transplants work, and trying to make them more widely available for patients, so we can help people. Hopefully we can move beyond human donors and identify the specific bacterial agents that are so important to this process. And then we can isolate those and then just give those to people in the future.

We’re basically trying to reverse engineer fecal matter. We’re trying to figure out ways to eliminate the need for human donors and be able to grow these bacterial communities in large-scale fermenters in the future—similar to the way we use traditional probiotics now.

Until then, what’s the transplantation process like?

From a stool sample of a healthy person, we pull out the bacterial fraction that is used for the therapy, and there are a number of ways to deliver it to the patient. The most common is via colonoscopy.

But we’re developing a pill that basically consists of this bacterial community that’s been freeze-dried and put into a capsule that is formulated in such a way that it survives the stomach and releases its payload in the gut. That pill should replace the need for a colonoscopy; it’s a really simple intervention.

We’re studying this in clinical trials right now throughout North America. And it has not yet let anybody down.

Talk some more about C. difficile. And does this procedure cure it or just treat it?

It’s safe to say it’s been curative for many patients.It’s kind of interesting how I ended up going from researching the microbiome to running a stool bank—definitely not what I expected to do after MIT! (laughs). But my fiancée’s cousin actually had C. diff while I was at MIT, and at the time there were very few people in the country that were doing fecal transplants. It was just this weird fringe medicine at the time; there was evidence that it worked, but no one really understood how or why it worked.

He was sick for about a year and a half. He failed seven rounds of Vancomycin—a standard antibiotic used to treat these infections. I went to meet her family for the first time at Thanksgiving, and her cousin is like, “Hey can I get a fecal transplant?” He had read all the primary literature, because he was so desperate to find something that worked, and he knew I had been researching it too. He ended up doing a treatment at home with a friend as a donor, and it worked for him.

Treatment at home? I’m afraid to ask . . .

It’s pretty unpleasant. He got a stool sample from his friend, put it in a blender, then put it through a coffee filter, and then put that liquid into an enema. And it worked. And that’s part of why I’m doing what I’m doing today.

There are half a million people a year in the United States that have C. diff, but at the time, fecal transplant treatments hadn’t been approved by the FDA, and no one was manufacturing it. So every patient had to find their own donor and get them screened. And then they have to go into the hospital, a highly regulated environment, and find a doctor willing to do this via colonoscopy. That’s kind of a tough ask. And then, it wasn’t clear who would pay for it. There are a lot of logistical barriers to actually making this available.

I figured this is similar to blood banking, right? Yeah, if you got in a car crash on your way home, you wouldn’t have to phone a friend to get blood, wait for a couple weeks to see if they were an okay donor, and then scour the country to find a doctor who could do this weird therapy. No, you just go in you get a unit of blood immediately and it would save your life. So we said there’s no reason we can’t do the same thing for stool, and so we did it.

It took a while to work out the logistics—the manufacturing process, how we’re going to screen the donors, how we’re going to work with the FDA. In 2013, the FDA basically said for patients that have failed all standard-of-care treatments, you can go ahead and get them treated with this therapy, without requiring the long and costly process for approving a new drug. So we said, great, we can go help out patients out right away. So we started this organization, OpenBiome, to fill that that need.

In 2013, we treated six patients. The first patient we treated had been sick over a year, so it was super exciting, because we had changed their lives. It’s pretty common for people to be sick for over a year, and a lot of them die, about 30,000 a year.

Does C. diff start when a person takes a course of antibiotics for something else?

Yes, it’s almost always associated with antibiotics. But once you have C. diff, it becomes its own separate story. Many healthy people actually have C. diff, but it’s usually out-competed and displaced by the bacteria that live inside of your gut. But when you take antibiotics, you can eliminate those bacteria. Then C. diff comes in sort of like a weed and takes over the community before the normal bacteria are able to re-establish themselves. So, if you haven’t taken antibiotics, it’s very unlikely you would get C. diff. But if you still have diarrhea a couple weeks after finishing a course of antibiotics, it’s a good idea to get tested just in case.

What’s it like for a patient to have C. diff?

Most people are relatively stable while they’re on antibiotics. But as soon as they go off antibiotics they get they get sick again—ten bowel movements a day, bloody stool, you can’t leave your house without wearing a diaper, enormous weight loss. One patient who got a fecal transplant from us told us she lost about 40 pounds and was down to about 80 pounds. It’s a terrible, terrible disease.

Back then, I convinced MIT to give me some space to run this manufacturing process, and we treated our first few patients. I went to somebody on the board and asked about getting a research grant. The model was that we would charge hospitals for every patient we help them treat, and we could grow the business from there. We got the grant, and we treated 1,800 patients in 2014 and 8,000 patients the next year. At this point, OpenBiome has treated about 47,000 patients and built a network of 1,200 hospitals in every state in the country.

The second patient we treated had to fly from Michigan to California for her treatment, because there were no local providers. But today, 98 percent of the U.S. population is within a two-hour drive of an FMT (Fecal Microbiota Transplantation) provider. When you have like terrible disease, getting on a plane is not a good thing for you or anybody else on the plane. So I’m really happy that now there’s almost universal access for these patients.

We’re still working on ways to scale this up further and make it more accessible to patients, and ultimately try to figure out how it works and develop these next-generation therapies that can hopefully improve on this and make the logistics a little bit easier.

How much does this procedure cost? And does insurance cover it?

A lot of C. diff patients end up in the hospital, which is quite costly. A recent study in Europe looked at the treatment costs for those patients who received fecal transplants and those that didn’t, and the upshot was that they saved about $25,000 per patient that gets the fecal transplant, mostly through avoided hospitalization costs. The cost of the procedure is $1,500 for the material, plus the colonoscopy, which is usually between $3,000 and $5,000. So the biggest piece of the cost is actually the procedure, and that’s one of the things we hope to get rid of by developing the capsule, so you don’t have to have the colonoscopy.

And does insurance cover it?

Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. One of the challenges is that it’s not an FDA-approved therapy yet, but we’re working on that. And once it’s FDA approved, it’ll be much easier for insurance companies to cover the costs.

What else is Finch working on?

In other diseases like ulcerative colitis, not every donor works, and we don’t know why. So we’re trying to figure out why, and we’re isolating the bacteria that seems to be driving efficacy in the patients. We also have a study on autism, which also turns out to be strongly associated with exposure to certain microbes.

Check out this explainer video about “poop transplants.” And no, it’s not gross.

______________

(Editor’s note: Shortly after we interviewed Smith, news broke about a patient—not one of Finch’s or OpenBiome’s—who died from a tainted fecal transplant, resulting in an FDA warning. In an email, Smith noted that the tragedy resulted from substandard screening; indeed, the victim received a transplant that included a strain of the E. coli virus. Finch and OpenBiome, which already do rigorous screening, released a statement here.)

The post Straight to the Gut appeared first on ORBITER.