People tend to bandy around the term “scientific consensus” a lot, particularly when talking about climate change. When 97% of the scientific community agrees that climate change is a real thing, you have to wonder about the remaining 3%. Are they being true skeptics, or are they holding out for ulterior motives? Philip Kitcher blows the “skeptics” idea out of the water; the scientific consensus that human beings have been making the world hotter has been agreed upon for close to 100 years, and climate scientists who disagree are disagreeing with the fundamentals of science itself. Kitcher goes on to predict what havoc future generations might have to face if we don’t look hard in the mirror about climate change. We shouldn’t wait until lizards start living at the north and south poles to change our human behaviors—we should be the change today. Philip Kitcher is the co-author of The Seasons Alter:How to Save Our Planet in Six Acts.

So the sciences are always revisable. It’s quite astonishing when we look back into the past how different the views, the quite well-defended views and quite successful views of people in the past were from the views that we have today.

So science does change a lot. Now some people see in that grounds for doubt, but I like many other philosophers would want to say that no, what we see here is a considerable progression. It’s the ideas of the older generation get developed, extended, and refined in our newer views. And so it seems to me that what the essence of science is, is that it’s never final. Although it’s perfectly reasonable for the scientists at any given time to treat what they’ve got very strong evidence for as if it were the final truth because they know from reflecting on the historical development of the sciences that’s a very good way of getting to the views that will eventually supersede the views that they now have. So you can think about it if you like as a process in which taking very seriously the ideas that you now have after they’ve been subjected to all sorts of rigorous testing and rigorous reflection and then trying to build on those leads you to better and better views that give you more and more predictive power, control over the natural world and more success in the ways in which you want to intervene in various aspects of the world.

A lot of people are worried about various claims that get made. I mean in the case of climate science what seems to me to be the case is that people quite naturally hear the climate science consensus as a very powerful warning, something that might incline them to change their views and change the ways in which they live. And they want to know perfectly reasonably whether the evidence is sufficiently strong so that they should perhaps sacrifice things that they’re used to enjoying and used to doing. So I think there’s a reasonable form of skepticism here. But any analogy with a sort of 'yesterday it was this, today it’s that, tomorrow it’s going to be something else' approach to this seems to be completely unfounded. Climate science is built on views about the atmosphere that have been developed very successfully and in a very rigorous way from the nineteenth century to the present. There isn’t any doubt about the mechanisms of the greenhouse effect. There isn’t really any doubt about the evidence behind the consensus that says that we have contributed enormously to the warming effects that are now becoming apparent not only in the present but also from the record of the earth’s average temperature. So all of that is as well founded as other things that people take for granted that science tells them like that water is H2O. Like the law of falling bodies. Like the fact that the earth is round and so on and so forth. There’s no more reason to be skeptical about the basic consensus of climate science than there is about any of those other things.

Now when it comes to making very specific predictions about where particular catastrophes are likely to come in the next decades that’s extraordinarily difficult. And on that all we can do is to try to simulate the earth’s climate and how it’s changing and to arrive at good predictions for the future. And where we get a lot of overlap in various ways of trying to figure out the dynamics of the earth’s climate then we can be reasonably sure that that’s something that is likely to happen. So some of the forecasts about the future – rising sea levels, much more frequent heatwaves, much bigger storms, really very serious dangers for the habitability of some parts of the world, droughts – all of that sort of stuff in general is very, very well supported by the evidence. Can we say for sure how many heatwaves there are going to be within the continental United States between 2050 and 2060. No, we can’t. What we can say is that there’s a really high probability of a lot of difficult disastrous events that are going to challenge future generations unless we deal with it.

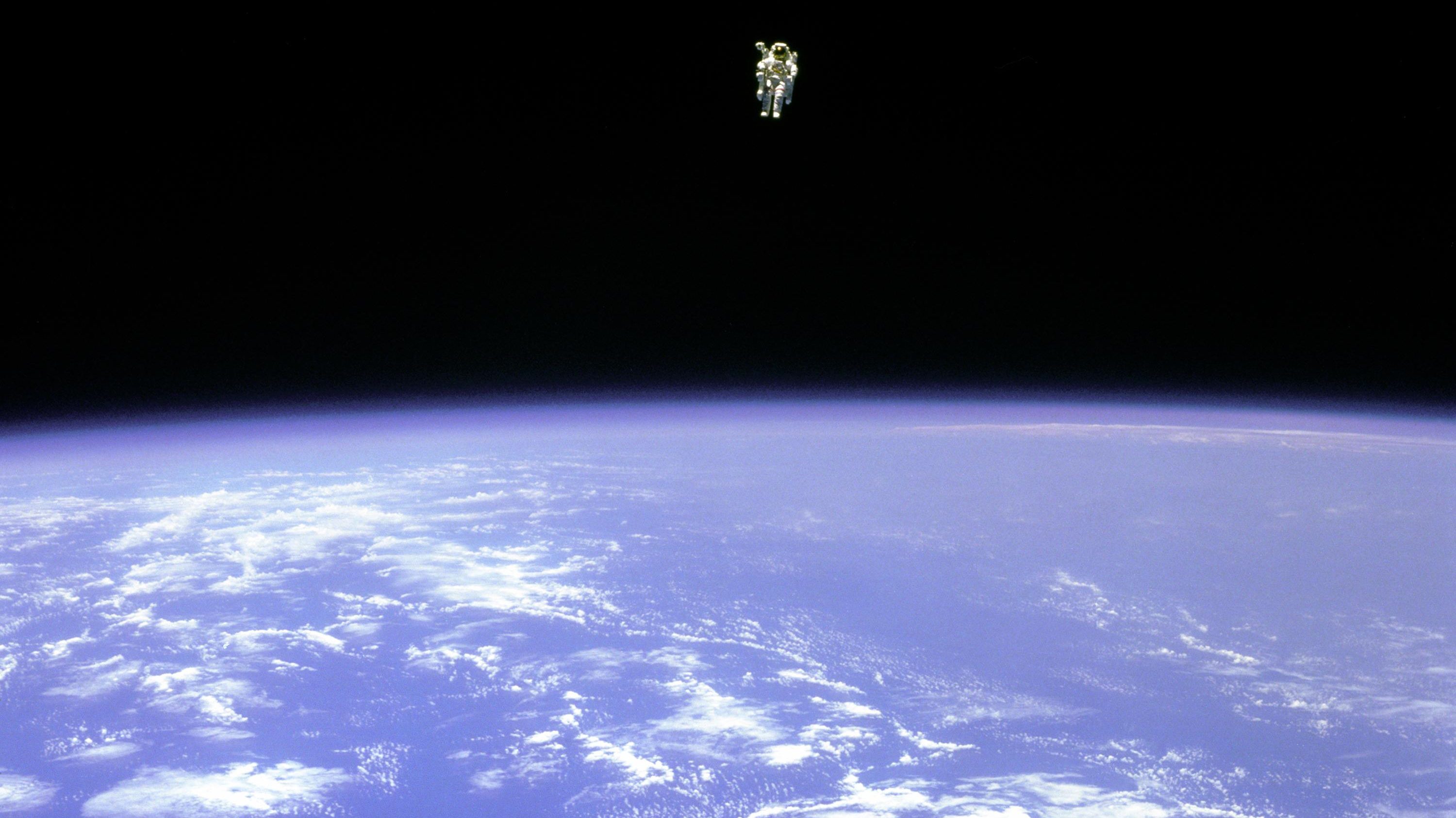

And we can’t say, for example, how much the temperature of the earth is going to rise by 2100 but one thing that’s really important to understand here is that 2100 isn’t some magical moment. I mean it’s not really going to matter that much if the temperature rises say four or five degrees Celsius if that comes in 2100 or whether it comes in 2120 or whether it comes in 2150 or whether it comes in 2200. That’s going to be a real disaster for human beings on our planet because five degrees Celsius above preindustrial temperatures is a world in which there’s no ice whatsoever and in which you’ve got reptiles that are able to live within both polar circles. It’s that hot.

That would be a world in which lots of the earth’s surface had become quite uninhabitable for us. So we’ve got to do something about it. And the evidence for that seems to be extremely strong. So I think the reasonable skepticism with which I began, the idea that, you know, people if they have to change their ways want to know whether there’s a good reason for it. That’s perfectly understandable. But if they looked at the climate science seriously and the evidence for it they would see what the tremendous risks to the future are.