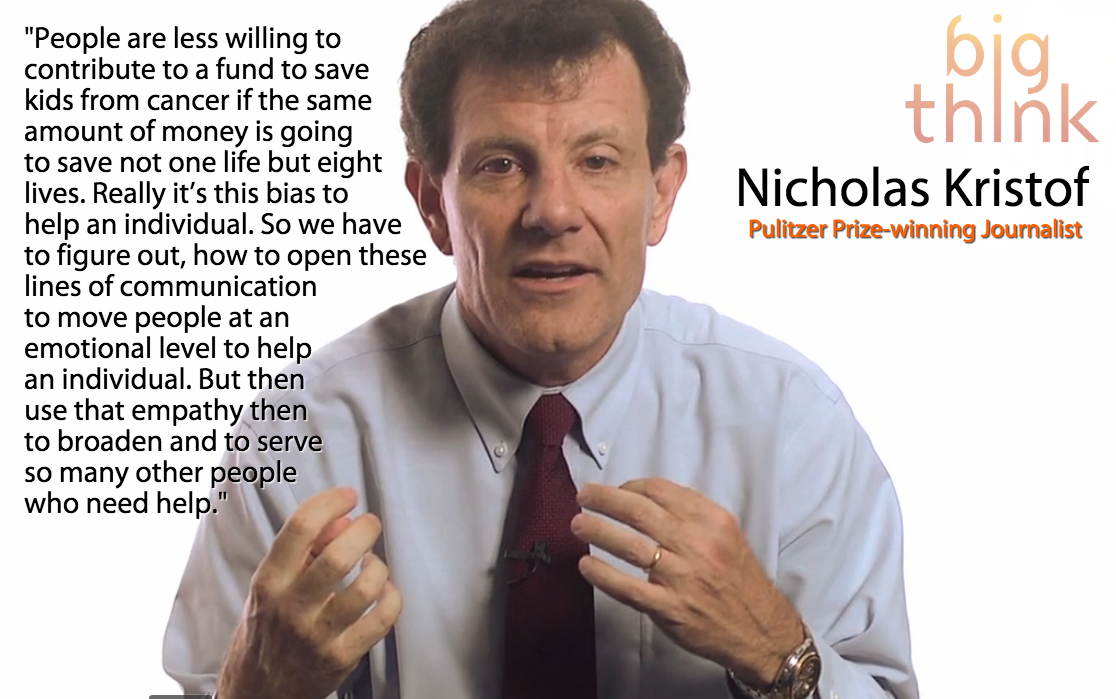

Pulitzer Prize winning author Nicholas Kristof describes research on what provokes charitable giving. Counter-intuitively, the plight of a single individual is more effective for fundraising than that of a group. Kristof is the co-author of A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity.

Nicholas Kristof: I have a new book out, A Path Appears, which is essentially about how to make a difference. And it addresses all those people who have this yearning to have an impact on the world, to find a measure of fulfillment but don’t really know how to go about that. And in working on the book my wife and partner in this effort, Sheryl WuDunn, one of the things we looked at is the kind of connections that link us to a cause and make us want to give, that make us want to participate in something. You know this arose for me, this research arose when I was writing for my column for The New York Times about Darfur back in 2004. And I was going to villages that had been burned out, talking to people who were survivors of massacres and it was frustrating me that I couldn’t get people to pay more attention to this. Meanwhile at that very same time here in New York City there was a red tailed hawk called Pale Male that had been kicked out of its nest in Central Park and New York was all up in arms about this homeless hawk. And I thought how is it that I can’t generate as much passion about hundreds of thousands of people being slaughtered as people feel for this hawk.

And that led me to this area of research, particularly by a guy called Paul Slovic. And it turns out that our engagement with a cause – it’s not about numbers, it’s not about classes of victims. It’s really about two things. First if all its emotional and it’s with individuals that we have evolved, we are hardwired to feel a certain amount of empathy and connection but with one other person whom we see and we can relate to. Not with 100,000 people half a world away. And the other thing is that we want to feel like we’re having an impact so we want some kind of a positive arc. We want to see a different being made. And so when aid organizations talk about five million people at risk and make it sound terribly depressing, they’re precisely hitting the buttons that turn people off. One of the things that really struck me was there have been experiments that ask people to do some math equations, solve some math problems first. And it turns out that if you do that, if you exercise the more rational parts of your brain then you’re less empathetic, you’re less likely to contribute. Those of us who care about these issues – we need to figure out how to do a better job of storytelling about individuals and showing that there is a possibility of hope.

Some of the research about our preference for helping individuals over classes of people comes from experiments where people were asked to contribute in some cases to this child, the one that was used was Rokia, a girl from West Africa versus a large group of people, millions of people suffering malnutrition in Africa. And of course everybody wanted to contribute to Rokia, to that girl. They wanted to help that girl. They didn’t really care about millions of people being malnourished. But what was striking is that, you know, even though we, I think, intellectually know that, you know, one death is tragedy and a million deaths is a statistic. That the point at which we begin to be numbed is when that number when N equals two. The moment you added not just Rokia but had a boy next to her and said you can help these two hungry kids, then people were less likely to contribute than if it was just Rokia. Likewise people are less willing to contribute to a fund to save kids from cancer if the same amount of money is going to save not one life but eight lives. Really it’s this bias to help an individual. So we have to figure out, I mean obviously the needs are vast and so we have to figure out how to open these lines of communication to move people at an emotional level to help an individual. But then use that empathy then to broaden and to serve so many other people who need help.

Directed / Produced by Jonathan Fowler, Elizabeth Rodd, and Dillon Fitton