Keats explains how a thought experiment in which he attempts to genetically engineer God allowed him to create a situation in which science and religion become compatible. The experiment further opened up an exploration of where the two seemingly irreconcilable elements can be made to merge.

Jonathon Keats: Science and religion both have very particular ideas about how the world works. Ideas that potentially are not totally compatible, but that are overlapping. Science claims to be a system that can discover absolutely anything that is totally comprehensive. Religion also claims a comprehensiveness that is based in reality where God, whatever that deity may be, is absolutely real, maybe even more real than anything or anyone else.

So I got to thinking that perhaps these two systems needed to find a way to talk to each other or at least to cross paths. And to do that, I took as the basis of a sort of a thought experiment, central beliefs from each of the two systems that seemed, on the surface, to be completely incompatible. Namely, I took God to be as literally real as you and I, as a building, a dog, a cat anything else. And I took science at its word that it could learn everything about everything about anything that was real, anything that had any substance in the world. To do that, I decided that I would attempt to scientifically figure out where on the phylogenetic tree, which is the master map of all the species on Earth, where you might put God. What species is God? That was a question that I asked myself. And then I had to find a way to address it scientifically. So science has many different ways in which you can pursue such a question.

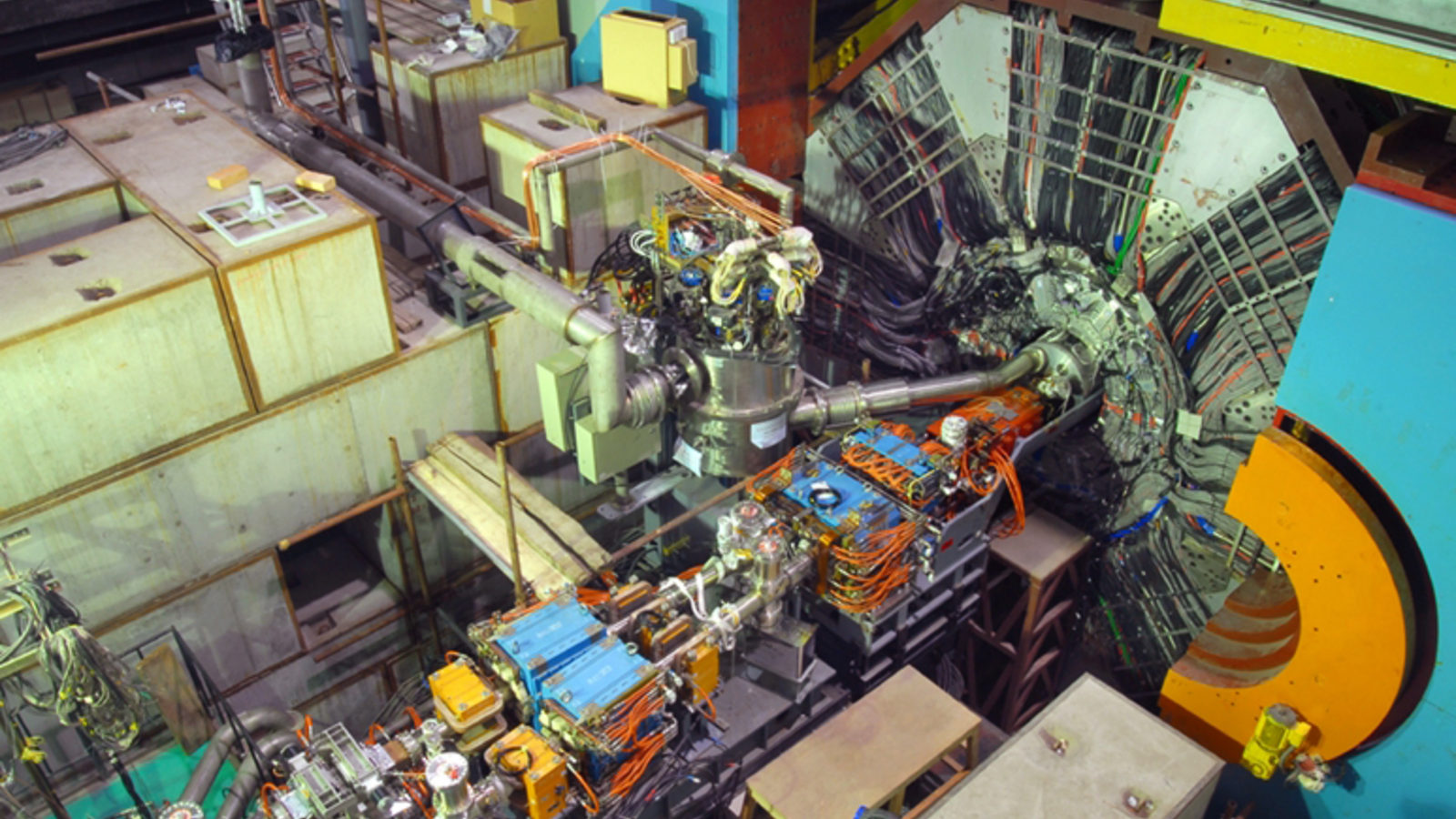

Probably the most obvious would be to obtain DNA for God, but I couldn't get my hands on that. So another possibility I realized was to attempt to genetically engineer God in a laboratory. And so I found collaborators at UC Berkeley and several other institutions who are willing to help me through that process using something known as Continuous in Vitro Evolution. Which essentially is an accelerated and directed version of natural selection in which you apply environmental pressures on a given population of an organism in such a way that you favor certain random mutations over others and you sort of force Darwin's hand. You put evolution in one direction versus another. It works very well, for instance, if we're talking about bacteria making them better able to absorb oil spills, for instance. But nobody had ever tried this in terms of attempting to genetically engineer God. So I set up my experiment and saw where it went.

I took two different candidate species, two species that were based on the best source material that I could find, the Bible for instance and various other religious tracks that, on the one hand, tell us that God came first and on the other hand that told us that God created man in his image. So it seemed that I should look to the earliest extant species, which are cyanobacteria, on the one hand, and I should like to humans on the other. Well humans are very difficult to work with in the laboratory over multiple generations so I worked with essentially a surrogate that was more or less the same when you look at the whole phylogenetic tree, which are fruit flies. So over the course of seven days and nights, the standard biblical period of time, I used Continues in Vitro Evolution in which my environmental pressure was prayer. I figured that since people are always praying to God, maybe there is some way in which God metabolizes worship. So I took leading prayers for each of the major monotheistic religions and as a control group I used exclusively talk radio. So over seven days and nights I ran the experiment. And then I looked for one of the qualities that is often associated with godliness as a way of measuring these two different species against each other in terms of their incipient godliness. That is that God is supposed to be omnipresent, which essentially sounds to me like rampant population growth. So I did population growth studies on both cyanobacteria and fruit flies, statistically adjusted according to their replication rate and various other factors in order to keep this absolutely scientifically on the up and up. And finally was able to publish my research, in which I discover, according to these two very preliminary pilot studies, that God is more closely related, phylogenetically speaking, to bacteria then to us. This is just the basis, of course, for many future experiments that I hope others will undertake having read this research and having figured out far better or certainly different methodologies for pursuing this sort of question.

Science and religion are considered by many, especially those who are adherents of one or the other, to be incompatible systems, systems that are irreconcilable and therefore that those who are the other side have to be converted. I don't think that that's necessarily the case. And so I was interested in this project, in this thought experiment in trying to figure out whether there is a way in which these incompatible systems could coexist in a way that they could each inform the other and could result in a broader understanding. Perhaps one that was more tolerant, certainly one that was more encompassing of beliefs that come over vast periods of time, are highly developed, and are essential to the way in which our world works. So I looked to both science and religion for certain core qualities. Religion tells us certain things about the nature of the universe. Science tells us certain ways to explore the universe. So what happens if we take the scientific method and we apply it to the religious realm that tells us certain baseline facts? We end up, I think, in an interesting place. One in which the scientific method doesn't any longer seem to be so absolutely all-encompassing.

That is to say that perhaps science can be a little bit less arrogant. On the other hand, I think that religion is shown through a process such as this to maybe take a little bit too much on faith. Is there a way in which the received wisdom of religion cannot be so rapidly and so uncritically received? So I'm not interested in converting anyone from one system to another. But rather in finding a way in which each system, by way of delving into the other and learning from the other, can become a better stronger system. A more satisfying and satisfactory one and one also that is capable of coexisting with the other in a way that is at peace because we're never going to convert everyone if we haven't already from science to religion or vice versa. So we need to find ways in which these systems can communicate with each other with due respect for what makes each system its own. The God Project is an attempt at achieving that. By no means perfect, but I think more broadly suggestive of a way in which any two or three or potentially more systems can potentially be brought into some sort of tentative alignment. And also can be strengthened through that process. You can't get through life, even through the day without coming upon incompatible systems.

Simply is the way of the world when the world comes complex as ours is that systems are not worked out to work together. There often is a lot of thought that goes into each system, but they don't naturally communicate because they probably come from different places and they serve different purposes. Yet you need to be able to negotiate all of this in terms of trying to resolve some sort of a personal problem or in terms of trying to take on some new venture in the workplace. These systems are in place and they can't be changed; they can't be supplanted, but have to be worked with. So I think that as I try to do, in the case of the God Project, I think that you can take systems for what they are and you can find ways in which, on the surface, they are incompatible. And you can put them together and try out combinations until you find some way that doesn't necessarily make them consistent with each other, but at least find some sort of a common ground, some sort of a peace that can be reached where each one of them can be true to itself and is not threatened. And yet both of them or all of them can work together in a way that symbiotically, in a way that collectively, they lead to something that is stronger for you and is more broadly, is more broadly applicable to everybody else.