The holiness of reality

For Julian Huxley, science was spiritual. The biologist, brother of the novelist Aldous Huxley and grandson of “Darwin’s Bulldog” Thomas Henry Huxley, thought evolutionary ideas hinted at humanity’s destiny: to safeguard the future of life on Earth and, by learning more about ourselves and the universe, expand the possibilities of humanity’s potential.

Rejecting the idea of the supernatural gave him enormous “spiritual relief,” he wrote in his 1927 book Religion Without Revelation. Understanding reality scientifically was a religious endeavor. Part of what it meant to be spiritual, he wrote, was:

the contemplation of our own selves and human nature, the miracle of its existence as a product of natural evolution, the amazing fact that a man is a mere portion of the common and universal substance of the world, but so organized as to be able to know truth, will the control of nature, aspire to goodness, and experience unutterable beauty.

Scientists today are finding Huxley was on to something. In a new paper, researchers found that, for some people, scientific ideas stir spiritual feelings of wonder and connection, which, they say, can offer psychological benefits similar to religious spirituality, like an increased sense of well-being and life satisfaction. And, on top of that, when scientific ideas inform people’s sense of spirituality, they come away with a better understanding of science. “Although science and religion differ in many ways,” the researchers write, their findings across three studies indicate that those human enterprises “share a capacity for spirituality through feelings of awe, coherence, and meaning in life.”

Spirituality of science reflects an attitude toward science not captured by belief or interest in science.

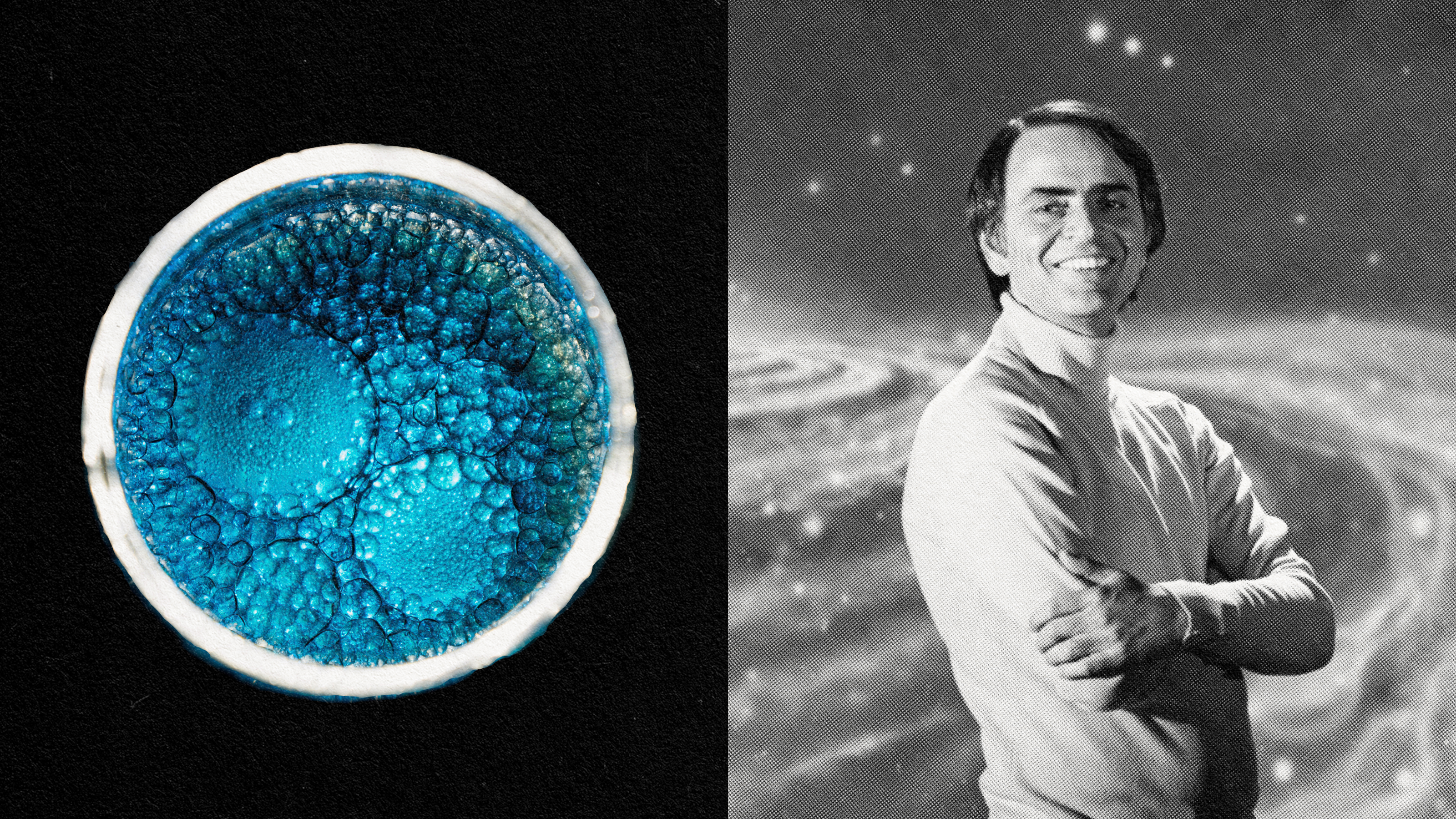

Jesse Preston, a psychologist at the University of Warwick, where she studies the nature of belief and what makes beliefs meaningful, led the research alongside a couple colleagues. What motivated the study, the researchers write, was their sense that psychologists were overlooking the spiritual side of science, focusing more on scientific understanding and trust in science. Of course, scientists have long attested to the cosmic feelings of significance science can spark in their lives. Einstein thought the highest religious feeling arises from recognizing the lawful harmony of the world. Preston and her colleagues offer a more contemporaryexample, from astronomer Carl Sagan: “When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual.”

In their first study, the researchers introduced a scale to measure people’s levels of scientific spirituality. They had 500 participants, roughly the same amount of men and women in their mid-30s, answer 10 survey questions, on a scale of 1 to 7 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) that gauge people’s degree of transcendent emotion, meaning, and connection through science. The resulting scale assesses the “spiritual relationship to science along three themes,” the researchers write—emotional elevation (“thinking about science brings me deep joy”), meaning (“there is an order to science that transcends human thinking”), and connection (“all things are connected through science”).

The scale strongly correlated with other science attitudes the researchers measured, like “interest in science” and “belief in science.” But only the spirituality of science scale, the researchers found, showed positive relationships with feelings of awe and spirituality. “This divergence suggests that spirituality of science reflects a unique attitude toward science that is not captured by belief or interest in science,” they write, “but which is characterized by its unique associations with awe and spirituality.”

Their second study, involving a similarly sized batch of participants who identified as atheist or agnostic, assessed people’s levels of well-being and life satisfaction. The results, they write, “illustrate the important psychological benefits of using science as a source of spirituality, beyond just belief in science.” A third smaller study found that participants’ levels of scientific spirituality predicted correct responses to questions about scientific subjects such as black holes. The idea is that spirituality of science “may promote science learning through stronger engagement with the material,” the researchers write.

“The majesty of grand scientific theories and their implications for understanding the nature of ourselves and the universe,” the researchers conclude, may be “particularly adept in eliciting the sense of coherence underlying spirituality.”

Or, as Julian Huxley put it, finding “holiness in reality.”

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.