Paradoxical philosophy: Why kids who know about Santa’s nice list cannot be on it

- Santa keeps a list of all the good and bad children. He gives presents to those who behave well and nothing (or maybe coal) to those who don’t.

- The problem is that if children do good things only because they want presents, then it strips that action of moral worth. Knowing about the list removes you from it.

- The issue is similar to that for monotheistic religions: Is doing something “because God is watching” actually that praiseworthy?

Two friends, Nick and Chris, are playing in the sandpit. They are building castles, digging holes, and doing all the things young kids should. But in the corner sits Natalie. She is all alone and looks sad. Nick feels badly for her and so decides to invite her over to play with them. He is a kind soul and wants Natalie to be happy. Just as Nick stands up to do his good deed, Chris says:

“Hey, Nick, I’ve got an idea. It’s Christmas next week. Let’s invite Natalie to play with us, so Santa puts us on the good list!”

“Err, okay,” Nick says. And so, they invite Natalie over to play.

So, who is the good boy? Nick, who wanted to be kind because it’s kind, or Chris, because he wanted to get the new Paw Patrol Mission Cruiser? Or does it matter?

This is the problem of Santa’s Naughty or Nice list, and it has surprisingly philosophical implications.

The wrong motivations

Let’s assume Santa knows every good and bad action a child does (ignoring his violation of privacy laws, for now). He tallies the scores, and using his highly enigmatic formula, decides who gets presents and who gets a lump of dusty coal. The question is whether an action can ever really be “good” if it is only done for the sake of material reward — to get a huge stack of presents. Can a child do anything, especially in December, without having at least one eye on Santa’s list?

The issue is whether our motivations make an action right or wrong. If Chris only ever acts morally because he wants to get on Santa’s good list, is this a truly good act? Intuitively, we want to say that such rampant self-interest rather diminishes an action’s moral worth. A good deed done for the sheer sake of being kind or loving or generous is better than one for which we are compensated.

For German philosopher Immanuel Kant, actions can only be called moral if they are “categorical” in this way — that is to say, they were done for their own sake. “Hypothetical” actions, like “if I do this, I’ll get a reward” are not bad per se, but depend too much on slippery fortunes. We must use our reason, as this is uniform and stable: Everyone can do good deeds, so everyone can be moral.

But is this realistic or even possible? Hume believed that reason could never motivate us to action. Reason can tell us how to do something, like how to get from A to B, but it cannot motivate us to actually start the journey to B. We need “passions,” like a desire for presents, to make us do anything. After all, biologically and psychologically, why do we do anything at all if it isn’t from the wanting of getting something from it — even if it is just praise or a lovely serotonin spike?

He knows when you’re sleeping, he knows when you’re awake

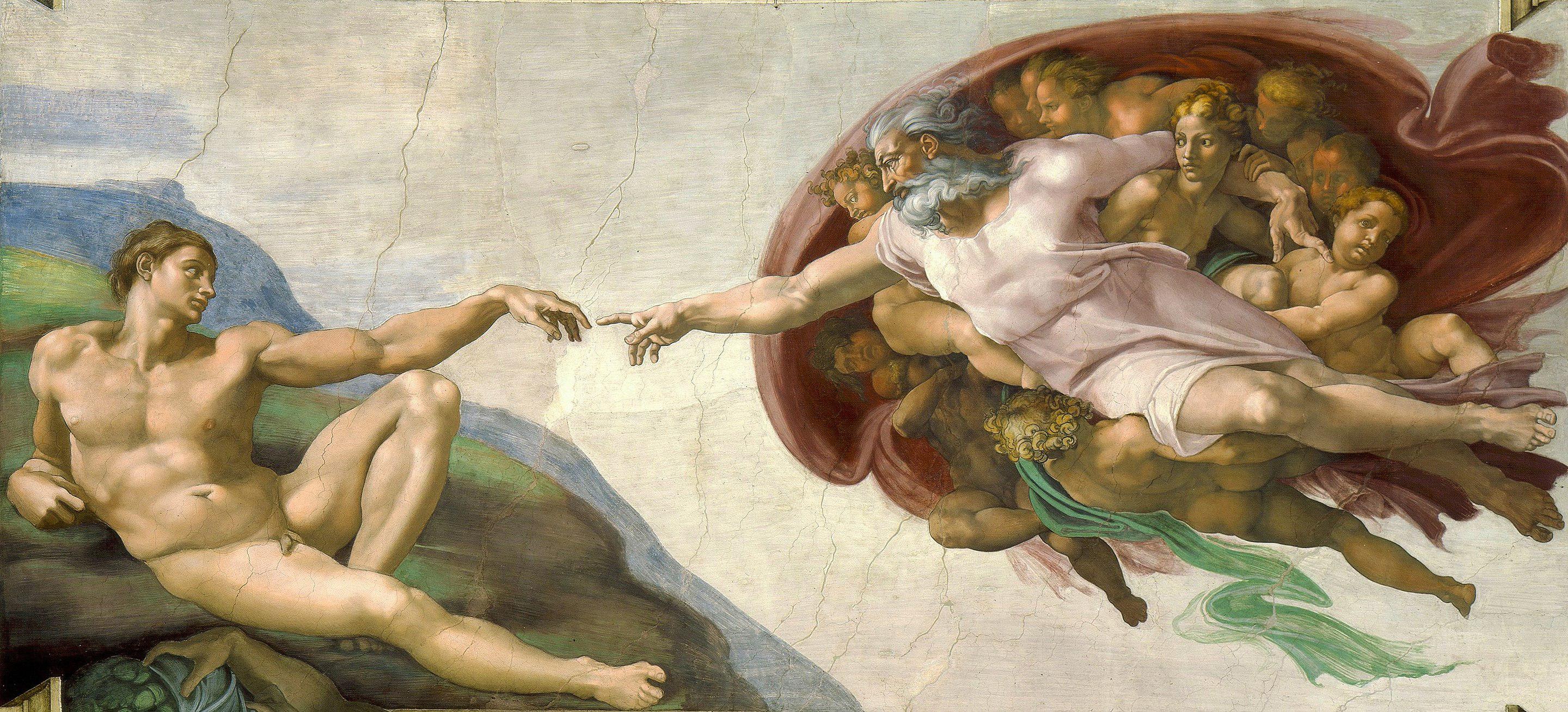

And, Santa isn’t the only bearded man in the sky watching and judging us. In the three major monotheistic religions of the world, you have an all-seeing God watching your every good and bad deed. For Muslims, Christians, and Jews, to be religious is to have at least half a mind constantly vigilant to the fact that there is a deity not only watching what you’re doing but what you’re thinking, as well.

In Catholic theology, there is also the idea of “imperfect contrition” or “attrition.” This is where the penitent is only confessing or avoiding sin from fear of hell, or want of heaven, rather than from genuine remorse. This is not enough to make the worshipper sinful — it is still an acceptable path toward piety — but it is seen as a less praiseworthy motivation.

To many atheists, the idea of only doing good because “God is watching” is pretty distasteful. Does it mean to say that if God were to take a holiday, we can all kill, steal, and abuse as much as we wanted? Did you only give me this birthday gift because it is a step on the stairway to heaven? Isn’t morality something that should be done for its own sake, not because of God’s saying so?

The paradox of Santa’s nice list

So, there is a problem with Santa’s naughty or nice List, which goes like this:

1. Santa will give gifts only to children on his good list — that is, those who do good deeds.

2. A deed cannot be good if it is self-interested and/or done for material reward (like gifts).

3. A child who knows about Santa’s list will act from self-interest.

Therefore, any child who knows about Santa’s list cannot be on it.

So, if you want to be kind to the children in your life this year, don’t tell them about Santa’s list. Tell them that Santa’s not watching or that he’ll give presents to everyone. And, if you know anyone who is being kind just because they want presents, it is not too late to wrap that piece of coal.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.