A group of Chicago tourists returned from China carrying a novel influenza virus. Virulent and transmitted through human contact, the disease quickly spread across the country. Hospitals were overrun with patients. Medical supply chains failed. First responders and their families soon became the second wave of victims. And the U.S. federal government, lacking both funding and a plan, floundered in its response.

All told, the disease infected 110 million Americans — more than 580,000 died.

Sound familiar? If not for a few noticeably off details, this story could be a recounting of the COVID-19 pandemic. But it’s actually a summary of Crimson Contagion, a simulation exercise run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2019.

The exercise aimed to measure the federal government’s capacity to respond to a viral pandemic, and its findings showed that the U.S. was woefully unprepared. It lacked sufficient funding, production capacity, and clarity on the roles of different agencies. Nor were these frailties unanticipated; they stood in line with two decades of similar analyses.

The risk was clear: When a pandemic hit, not if, the government would be unable to muster the U.S. health system to meet the threat.

The government’s response to HHS’s warnings and recommendations? Nothing. A year prior, the White House had dismantled a National Security Council directorate for pandemic preparedness. Nothing substantial replaced it.

It’s an anecdote that wouldn’t be newsworthy if not for the timing. A few months after the report, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Then-President Donald Trump would later claim coronavirus “blindsided the world.”

Risky business

Retired U.S. Army General Stanley McChrystal opens his book Risk: A User’s Guide (co-authored with Anna Butrico) with the story of Crimson Contagion because it points to an important fact: We are lousy at assessing risk.

Whether as nations, organizations, or individuals, we tend to overestimate our vulnerability to improbable threats, underestimate the likelihood of credible ones, and assume we have far less agency than we do.

“In retrospect, Crimson Contagion was a diagnosis whose illness went untreated,” McChrystal writes. “The simulation accurately predicted our unpreparedness, and the subsequent outbreak of COVID-19 revealed failures across a range of factors that were ultimately in our control — factors we must learn to understand and influence if we are to effectively manage risk.”

And the pandemic was hardly a solitary misjudgment. As McChrystal noted in an interview with Big Think+, the last few decades have seen several high-profile risks come to realization. The 9/11 attacks and the Great Recession are two prominent examples.

Not a prediction. Just predictable.

Of course, it’s easy to look to the past and argue that any disaster could have been averted had only this or that person gone with plan B instead of plan A. Such backward forecasting isn’t McChrystal’s project, though. Misfortune happens, and some risks are inescapable.

His point is that none of these threats “blindsided the world.” The risks were known in advance. Precedent alone forewarned their potential as history has been plagued by not only pandemics but terrorist attacks and unregulated bubbles that went pop.

Yet, those in charge of managing these risks took a blasé attitude to the system’s vulnerabilities instead of proactively controlling what they could. Had they done so, yesterday’s leaders might have reduced the damage done.

“If you go across any number of crises that come, in many cases those risks were actually very predictable — not in an exact time or form — but in the fact that they would arise,” McChrystal said.

Credit: Shobhit Gosain / Wikimedia Commons

The risk equation

To help people better think about risk, McChrystal has created a simple equation: Threat × Vulnerability = Risk.

This equation isn’t meant to be an exact science. McChrystal doesn’t advocate for calculating risk to the nth decimal before taking action. Rather, his aim is to provide a shorthand for adjusting our attitude toward risk. He wants us to better conceive of and anticipate risk by assessing the relationship between the external threat and our internal vulnerability.

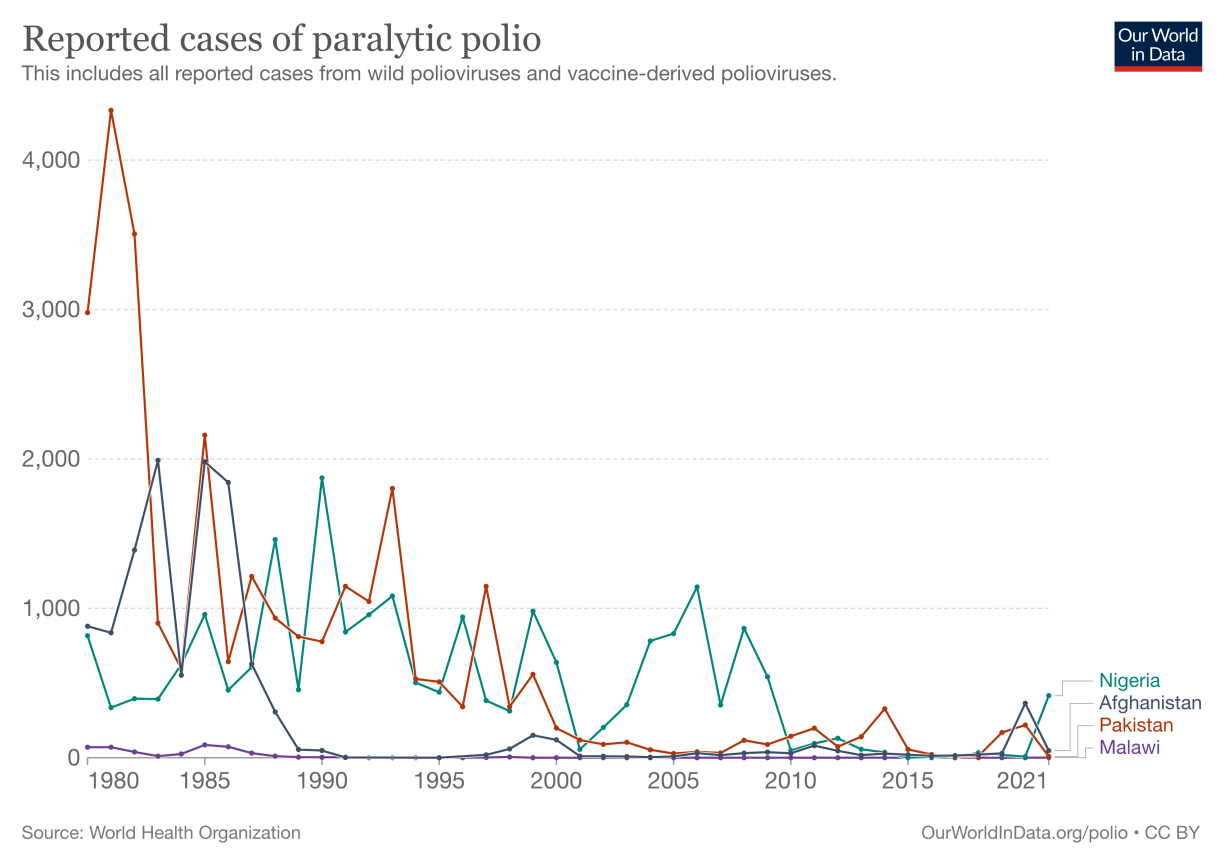

Polio offers an applicable example. This frightful disease can cause fatal paralysis if it affects the muscles used for breathing. It’s also very threatening due to its high infection rate, especially for children in poor or marginalized communities where medical resources are sparse. Because polio is so threatening and children so vulnerable, the risk for such communities multiplies.

However, people aren’t without recourse. The polio vaccine is 99-100% effective, and while there’s no cure, the vaccine can prevent infection in children who receive a full four-dose regimen.

Using McChrystal’s equation, we see that no matter how threatening polio may be, the risk is effectively zero as long as the vulnerability remains so low. (Any number multiplied by zero is zero, after all.) And the last few decades have witnessed that calculation play out in real-time.

The World Health Organization, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, and their partners have set out to immunize children across the world. Thanks to such efforts, polio cases worldwide have shrunk from an estimated 350,000 in the early 1980s to a reported 33 in 2016. Today, the risk of polio in much of the world is zero, and the number of communities that remain vulnerable is shrinking.In time, hopefully, polio will join smallpox as a disease that no longer threatens anyone.

A defense-oriented mindset

While ‘risk zero’ isn’t always a possibility, we can still reduce risk by managing those variables within our control.

“So, what do we have control over? Our vulnerabilities,” McChrystal said. “Not complete control, but we have a lot of agency there. We can make ourselves stronger. We can make ourselves more able to withstand threats that arise.”

This was the HHS’s hope with Crimson Contagion.

Novel diseases are an external threat that we will never dominate. They spring up as evolution does its thing, and some microbe will eventually find humans a fitting host. We will always be at risk, but any step taken to reduce vulnerability simultaneously reduces that risk and, if we’re thoughtful, the fallout.

Had the federal government taken the HHS’s recommendations, it would have shored up production capacity, clarified the roles of federal agencies, and developed communication channels between those agencies and the public. None of which would have prevented the pandemic, but any one of which may have helped us navigate it with less confusion, waste, and loss of life.

If you strengthen your risk immune system, when the unexpected happens — which you should expect — you’re going to be more resilient.

– Gen. Stanley McChrystal

Strengthening our risk immune systems

By changing our attitude toward risk, we can begin the work of strengthening what McChrystal calls our “risk immune system.” Like a body’s natural immune system, a risk immune system can’t eliminate external threats. But once it detects them, it can assess, respond to, and learn about them to limit vulnerabilities and the risk of future exposure.

Like its bodily counterpart, the risk immune system is only as strong as the habits and routines that maintain it. In place of exercise and diet, McChrystal recommends strengthening a risk immune system through what he calls “risk control factors.”

In his book, he recognizes and discusses ten such factors: communication, narrative, structure, technology, diversity, bias, action, timing, adaptability, and leadership. Each one of these scales from assessing personal risk up to the risks faced by organizations and societies. For this article, we’ll preview biases and assumptions.

Biases and assumptions are rooted in our experiences and knowledge. While unavoidable, left unexamined, they can degrade our risk immune system by affecting our judgment. That’s because, as McChrystal writes, they have the power to “refract facts and realities in a way that can prevent the accurate identification, assessment, and mitigation of risks.”

Thinking about risk

Some historic examples of assumptions leading to people exposing themselves or others to unnecessary risks:

- Many banks, investors, and even the SEC failed to perform their due diligence in questioning Bernie Madoff’s investments. They assumed past performance guaranteed future credibility. In reality, Madoff was running a multi-million dollar Ponzi scheme.

- Multi-level marketing companies, such as Amway, use “imperfect disclosure” during recruitment pitches to prey on people’s biases by focusing on outlier successes instead of typical cases. Once they’ve joined, people often have difficulty leaving thanks to the inertia bias — the tendency to stick to a chosen course of action.

- Many people have chosen not to be vaccinated against COVID-19 because of the extremely rare side effects, such as inflammation of the heart muscles (myocarditis). They may assume that inaction is less risky, yet myocarditis and a host of other risks are much more severe in those infected with COVID-19.

These show that while external threats exist, the risk multiplies only after a poorly considered action on our part. As McChrystal said, “It all comes back to the idea that the greatest risk to us is us.” McChrystal said. “[But] if you strengthen your risk immune system, when the unexpected happens — which you should expect — you’re going to be more resilient.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Stanley McChrystal’s expert class for your organization, request a demo.