Who was the most influential philosopher ever?

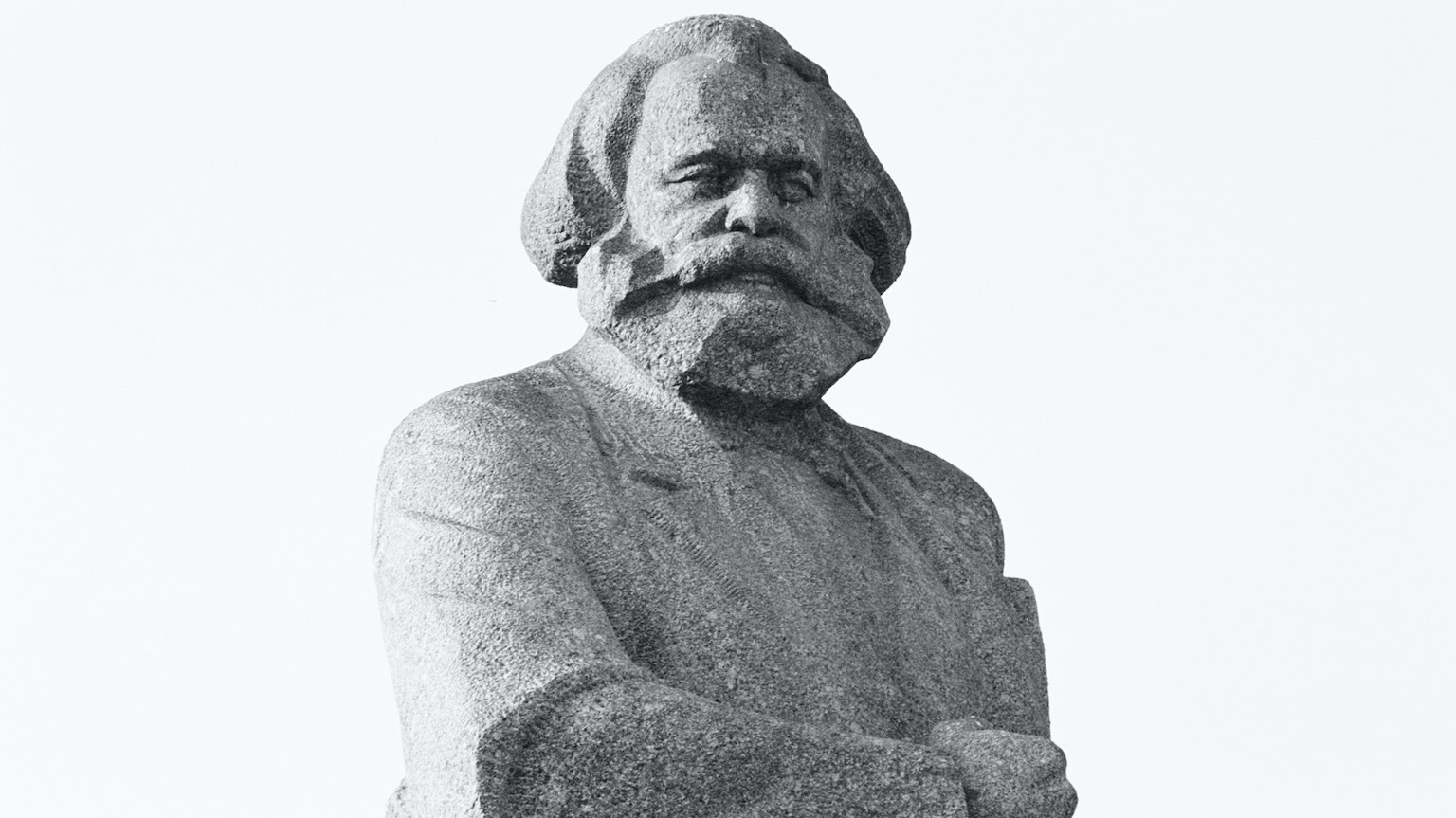

- Karl Marx defined a way of seeing history that focused on grand, sweeping socioeconomic change.

- Via Lenin, Mao, and Stalin, Marx became one of the most influential philosophers of all time, which is exactly what he set out to do.

- Few thinkers are as controversial as Marx, yet few people have actually read his ideas. Many more mistakenly confuse his ideas with what later thinkers said about them.

There is great insight to be found in philosophy, not to mention a lot of fun. By contemplating ideas and the world around us, we can uncover truths about ourselves or the universe that transform how we see and interact with everything around us. But, it is also fair to say that the hours spent and libraries written debating if other people have minds, whether the world is a simulation, or just what we would do if we lived in Nazi Germany are abstract concerns. Much of this philosophy is easily left behind in lecture halls and dorm rooms.

But that sells short the huge and transformative power of ideas. Behind everything we all do, the very reason we get out of bed, is an idea or purpose. It might be some religious or existential belief, an ethical red line, or a deeply entrenched political loyalty, but we each live by and sometimes for some ideology. Inscribed on Karl Marx’s grave are the words “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” And few people changed it as much as he did. Like him or loathe him, people ought to read Marx to see why his ideas had such a huge impact. (As it so happens, Karl Marx was ranked as the most influential scholar ever, out of a group of 35,000.)

A new way of seeing history

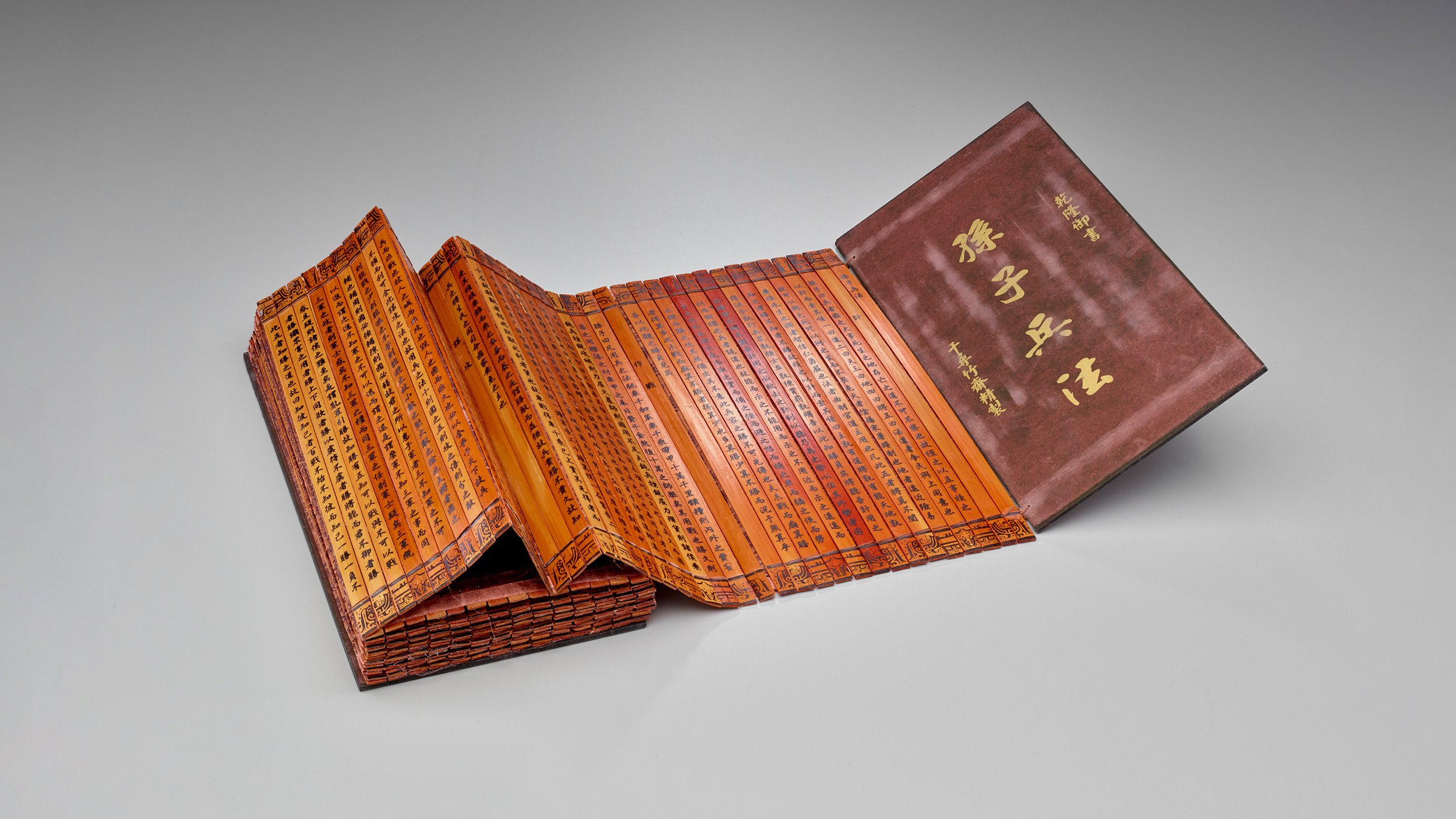

While historians and philosophers before him (such as the North African, Ibn Khaldun) had done sociological, grand-sweep analyses of history, no one did it with the systematic rigor of Karl Marx. He inherited from Hegel the idea of a “dialectic,” which maintains that the progress of history is marked first by a “thesis” (one position, technology, ideology, etc.), an “antithesis” (a contrasting or oppositional position), and the interaction of the two, which creates a “synthesis” (a better, fuller, and more advanced compromise position). But Marx purged Hegel of his more quasi-religious spiritual elements and instead saw history in entirely atheistic “material dialectic.” For Marx, every moment in history, from the dawn of mankind to the brave new worlds of the future, could be explained (even predicted) in material, especially economic, language.

We live with this, today. Gone are the “great man theories” of history. Individuals even as grand as presidents, popes, and conquerors are only a sideshow against wider sociological and economic factors. Every time we talk about the “root causes” of gun crime, poverty, antisocial behavior, or gang culture, it is a subtle nod to Marx. When James Carville, strategist for Clinton’s successful 1992 campaign, coined the phrase, “It’s the economy, stupid,” he was revising a point Marx made. Less certain is the notion that when Jessie J sang the lyrics, “It’s all about the money, money, money,” she was providing a wider commentary about dialectical materialism.

When life throws you Marx, make Leninade

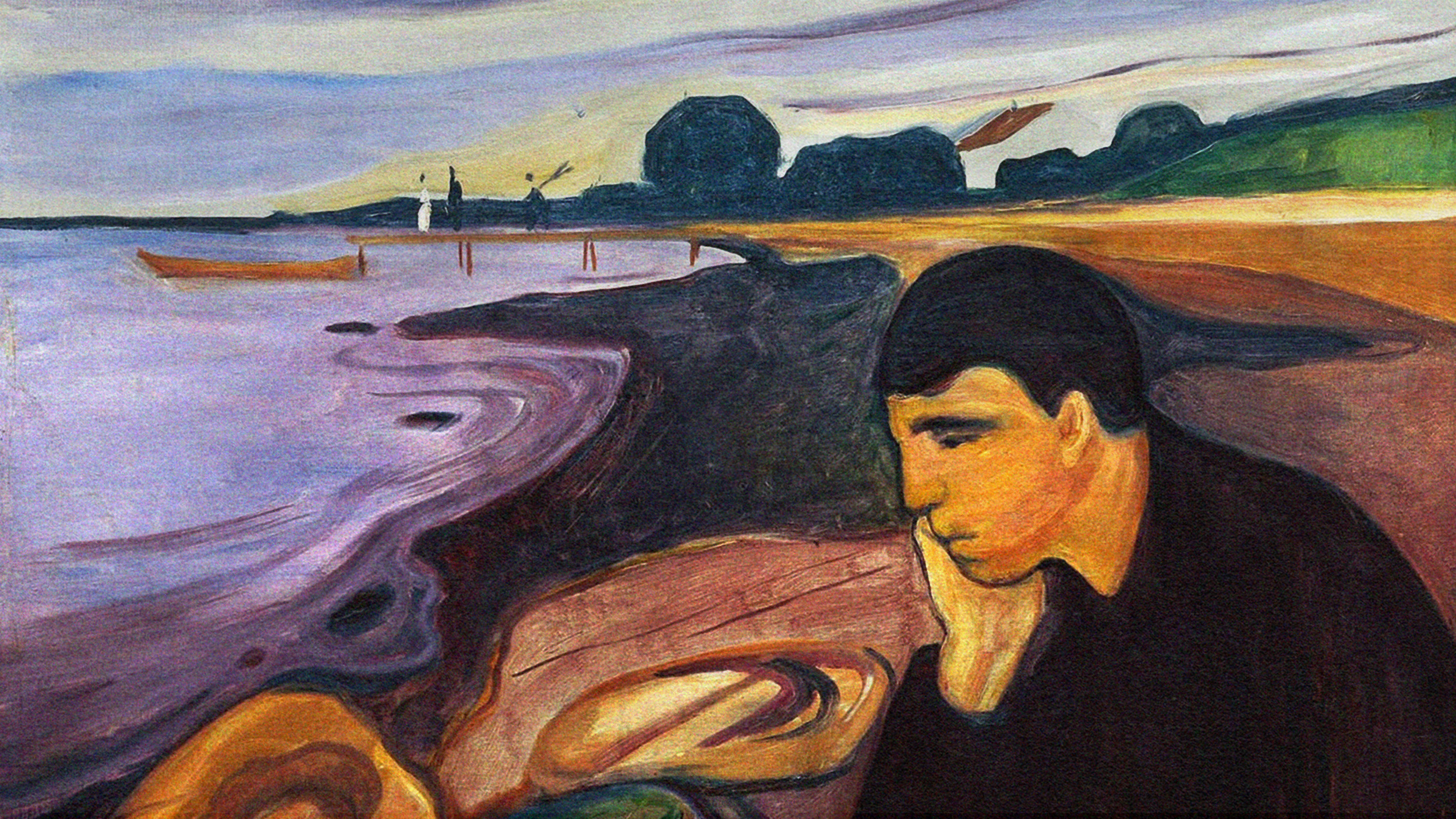

The biggest influence Karl Marx has today comes from his examination of capitalism and his account of communism. Marx framed capitalism within its historical period and saw it as only the current stage in human progress or a step along his dialectic. He called out a lot of capitalism’s issues — such as great inequalities — and presented compelling cases about why it leaves many so unhappy, such as a sense of alienation from the jobs we have and the companies we work for.

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.

Karl Marx’s Epitaph

The problem with Marx, as The Economist wrote in 2017, is that “his solution was far worse than the disease.” And so, he got a lot wrong. His Communist Manifesto also lacked the scientific predictive power Marx thought, not least because capitalism stubbornly sticks around. Yet, this dense and often hard to understand piece of philosophy inspired communist revolutions all around the world — ironically, precisely where Marx thought that they would not occur. (He thought they would happen in advanced stage capitalist countries like Britain and not pseudo-feudal societies like Tsarist Russia.)

And, in that, lies Marx’s huge legacy. Via Lenin and Stalin, Marx’s ideas worked their way into what became the USSR. Via Mao it became the Chinese Communist Party. Revolutions and revolutionaries around the world, from Vietnam and Cuba to Yugoslavia and Cambodia, were inspired by what they read in Das Kapital. By the mid-20th century, just over a third of the world was run by governments that called themselves (genuinely or not) “Marxist.” Today, generations of capitalism’s discontents still turn again and again to what they read in Marx. So much of our modern political debate uses or challenges what Marx wrote, and the old lines of the Cold War still define geopolitics today.

Don’t bring Marx up at Christmas

Karl Marx is one of the most controversial thinkers in the world. His works are challenging, original, and littered with information and erudition. But they also lend themselves to a fanaticism and self-assurance that borders on the religious or maniacal at times. Most people wrongly think Marxism is the same as Leninism, Maoism, the Cold War, or even the broader idea of “socialism,” but very few people have actually read what Marx wrote — including those who adulate or denounce him. But it is hard for anyone to dismiss his huge legacy or impact, even if you see that as horrific rather than utopian.

While other political philosophers like Adam Smith, Thomas Hobbes, or Plato no doubt had huge impact, they cannot be so easily pointed to as a direct cause or motivating factor for global change (although Smith comes closest). And while it is true that Engels was responsible for bankrolling Marx’s work and served as a close friend and intellectual collaborator, he did not produce the compelling and transformative works of Karl Marx.

On the question of influence, Marx gets full marks.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.