How philosophy blends physics with the idea of free will

- People feel like they have free will but often have trouble understanding how they can have it in a deterministic universe.

- Several models of free will exist which try to incorporate physics into our understanding of our experience.

- Even if physics could rule out free will, there would still be philosophical questions.

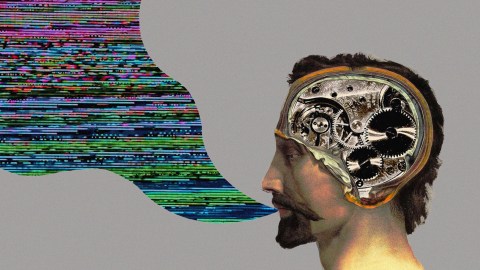

Most people with a scientific worldview agree with the idea of causal determinism, the notion that everything is subject to the laws of physics, and anything that happens is the result of these laws acting on how things exist in the world or existed in a prior moment. However, it can be challenging to figure out how this idea meshes with the notion of free will.

After all, if everything else is subject to causal determinism, how can we not be? How can our decisions be somehow exempt? Many people argue that we obviously are also part of a clockwork universe and that physics kills off free will.

But is this saying too much? Can we really treat free will as the subject of physics alone? Today, we’ll consider some stances on free will and how they relate to physics alongside some philosophers’ ideas on if we can outsource our views on the human experience to science.

Some philosophers have taken the argument of casual determinism mentioned above and used it to say that there is no room for free will at all. This stance, called “hard determinism,” maintains that all of our actions are causally necessary and dictated by physics in the same way as a billiard ball’s movement.

The Baron d’Holbach, a French philosopher, explained the stance:

“In short, the actions of man are never free; they are always the necessary consequence of his temperament, of the received ideas and of the notions, either true or false, which he has formed to himself of happiness; of his opinions, strengthened by example, by education, and by daily experience.”

While physics and philosophy have both advanced since the enlightenment era, hard determinism still has supporters.

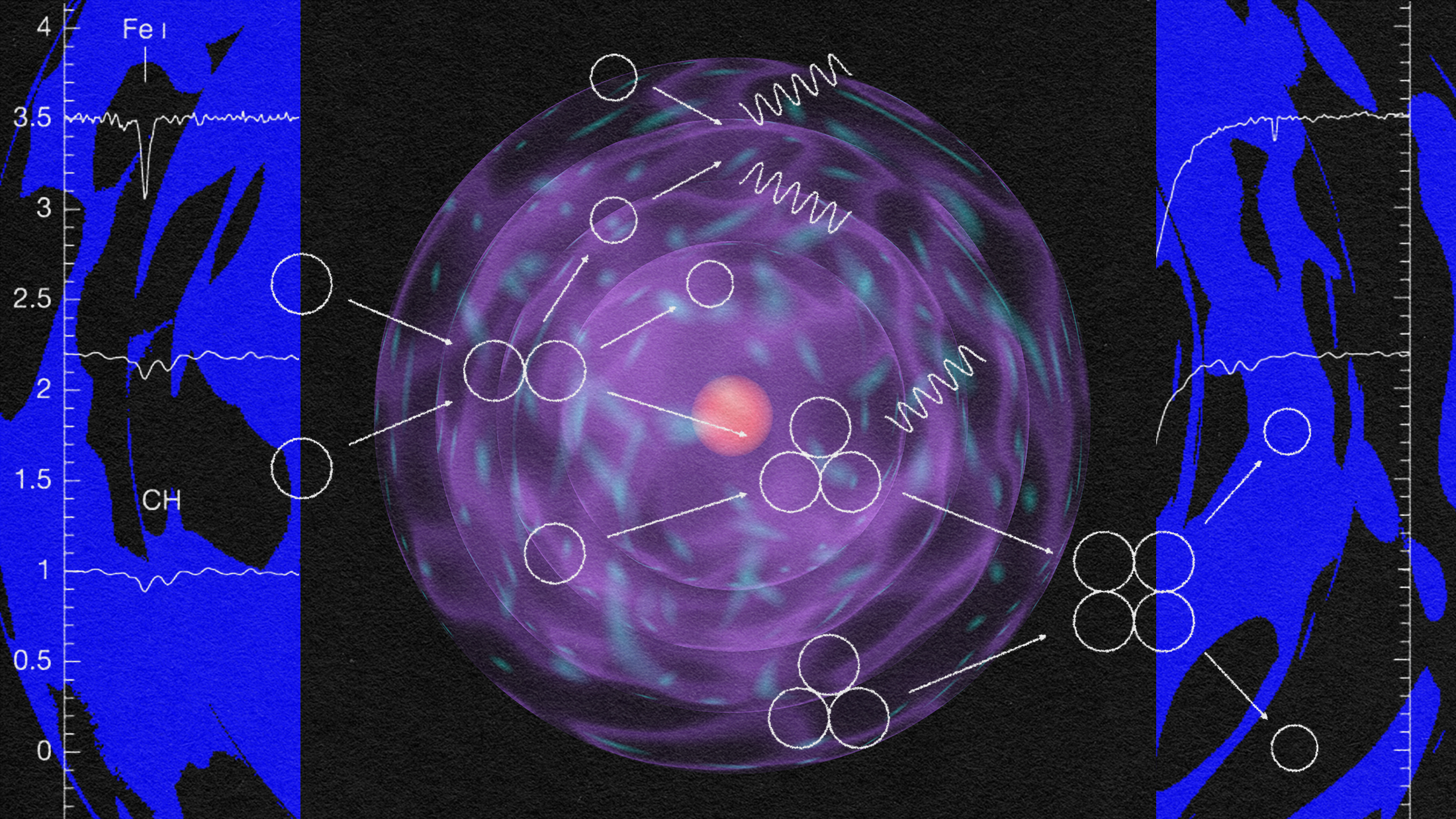

As some of you are probably thinking right now, quantum physics, with its uncertainties, probabilities, and general strangeness, might offer a way out of the determinism of classical physics. This idea, sometimes called “indeterminism,” occurred to more than a few philosophers too, and variations of it date back to ancient Greece.

This stance holds that not every event has an apparent cause. Some events might be random, for example. Proponents of the perspective suggest that some of our brain functions might have random elements, perhaps caused by the fluctuations seen in quantum mechanics, that cause our choices to not be fully predetermined. Others suggest that only part of our decision-making process is subject to causality, with a portion of it under what amounts to the control of the individual.

There are issues with this stance being used to counter determinism. One of them is that having choices made randomly rather than by strict causation doesn’t seem to be the kind of free will people think about. From a physical standpoint, brain activity may involve some quantum mechanics, but not all of it. Many thinkers incorporate indeterminism into parts of their models of free will, but don’t fully rely on the idea.

Also called “compatibilism,” this view agrees with causal determinism but also holds that this is compatible with some kind of free will. This can take on many forms and sometimes operates by varying how “free” that will actually is.

John Stuart Mill argued that causality did mean that people will act in certain ways based on circumstance, character, and desires, but that we have some control over these things. Therefore, we have some capacity to change what we would do in a future situation, even if we are determined to act in a certain way in response to a particular stimulus.

Daniel Dennett goes in another direction, suggesting a two-stage model of decision-making involving some indeterminism. In the first stage of making a decision, the brain produces a series of considerations, not all of which are necessarily subject to determinism, to take into account. What considerations are created and not immediately rejected is subject to some level of indeterminism and agent control, though it could be unconscious. In the second step, these considerations are used to help make a decision based on a more deterministic reasoning process.

In these stances, your decisions are still affected by prior events like the metaphorical billiard balls moving on a table, but you have some control over how the table is laid out. This means you could, given enough time and understanding, have a fair amount of control over how the balls end up moving.

Critics of stances like this often argue that the free will the agent is left with by these decision-making models is hardly any different from what they’d have under a hard deterministic one.

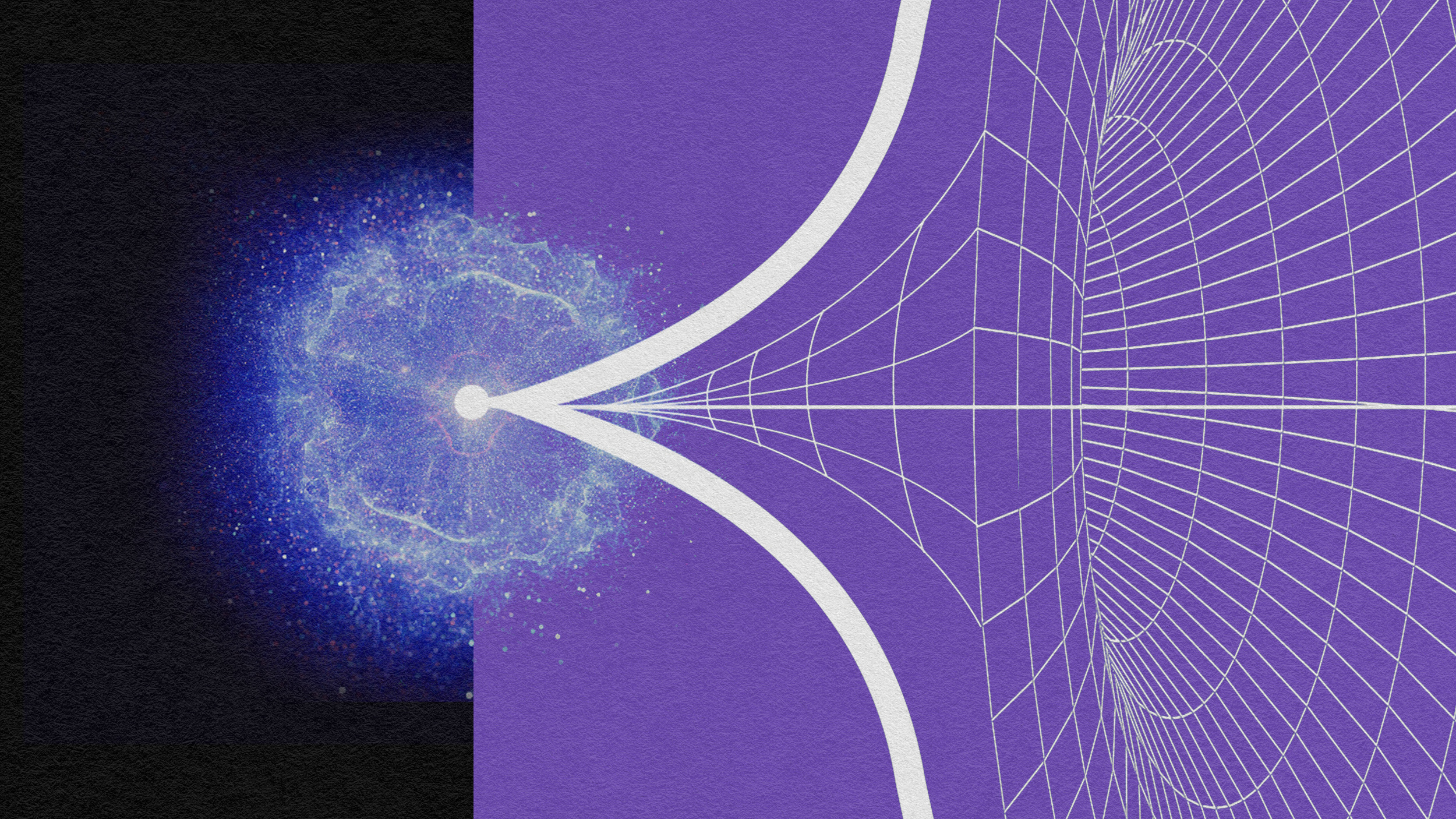

This is the stance with the premium free will people tend to talk about—the idea that you are in full control of your decisions all the time and that casual determinism doesn’t apply to your decision-making process. It is “incompatibilist” in that it maintains that free will is not compatible with a deterministic universe.

People holding this view often take either an “agent-casual” or “event-causal” position. In an agent-casual stance, decision-makers, known as “agents,” can make decisions that are not caused by a previous action in the same way that physical events are. They are essentially the “prime movers” of event chains that start with their decisions rather than any external cause.

Event-casual stances maintain that some elements of the decision-making process are physically indeterminate and that at least some of the factors that go into the final choice are shaped by the agent. The most famous living proponent of such a stance is Robert Kane and his “effort of will” model.

In brief, his model supposes an agent can be thought responsible for an action if they helped create the causes that led to it. He argues that people occasionally take “self-forming action” (SFA) that helps shape their character and grant them this responsibility. SFAs happen when the decisions we make would be subject to indeterminism, perhaps a case when two choices are both highly likely- with one being what we want and one being what we think is right, and willpower is needed to cause a choice to be taken.

At that point, unable to quickly choose, we apply willpower to make a decision that influences our overall character. Not only was that decision freely chosen, but any later, potentially more causally-determined actions, we take rely at least somewhat on a character trait that we created through that previous choice. Therefore, we at least partially influenced them.

Critics of this stance include Daniel Dennett, who points out that SFAs could be so rare as to leave some people without any real free will at all.

No, the question of free will is much larger than if cause and effect exist and apply to our decisions. Even if that one were fully answered, other questions immediately pop up.

Is the agency left to us, if any, after we learn how much of our decision-making is determined by outside factors enough for us to say that we are free? How much moral responsibility do people have under each proposed understanding of free will? Is free will just the ability to choose otherwise, or do we just have to be responsible for the actions we make, even if we are limited to one choice?

Physics can inform the debate over these questions but cannot end it unless it comes up with an equation for what freedom is.

Modern debates outside of philosophy departments tend to ignore the differences in the above stances in a way that tends to reduce everything to determinism. This was highlighted by neuroscientist Bobby Azarian in a recent Twitter thread, where he notes there is often a tendency to conflate hard determinism with naturalism—the idea that natural laws, as opposed to supernatural ones, can explain everything in the universe. .

Lastly, we might wonder if physics is the right department to hand it over to. Daniel Dennett awards evolutionary biology the responsibility for generating consciousness and free will.

He points out that while physics has always been the same for life on Earth, both consciousness and free will seem to have evolved recently and could be an evolutionary advantage of sorts—not being bound to deterministic decision making could be an excellent tool for staying alive. He considers them to be emergent properties we have and considers efforts to reduce us to our parts, which do function deterministically, to be unsound.

How to balance our understanding of causal determinism and our subjective experience of seeming to have free will is a problem philosophers and scientists have been discussing for the better part of two thousand years. It is one they’ll likely keep going over for a while. While it isn’t time to outsource free will to physics, it is possible to incorporate the findings of modern science into our philosophy.

Of course, we might only do that because we’re determined to do so, but that’s another problem.