Three thinkers on when we should call out harmful speech

Photo by Michelle Ding on Unsplash

- Modern debates over free speech rage on the internet, but what do experts say?

- Some think it is easy to go too far in limiting public debate by offending parties, others argue limits are part of normal discourse.

- While the debate isn’t settled, these thinkers can give you some starting points for your next discussion.

If you’ve been online in the past few weeks, you’ve probably come across at least one person discussing free speech. The debate over if it is threatened, who has it, who needs it, what it is, and what form it should take goes back long before the days of social media and the 24-hour news cycle.

Recently, the debate over what limits are being put on public discourse is the center of attention, with a great deal of focus placed on the question of what conversations are worth having. Some, including the signers of the famous Harper’s Letter, fear that free speech is threatened. Their detractors fear this is a front to keep the traditionally marginalized from expressing their concerns. Previous controversies have centered around who gets to speak at what institutions and if the withdraw of an invitation to speak, or the denial of it to begin with, is a kind of censorship.

But, are any of these concerns valid? What do experts on argumentation have to say about these issues? Today, we’ll consider three experts’ stances on when speech can be harmful, when people shouldn’t be given a platform, and when we should grit our teeth and suffer their opinion.

Dr. Hugh Breakey of Griffith University lays out his case in the essay “‘That’s Unhelpful, Harmful and Offensive!’ Epistemic and Ethical Concerns with Meta-argument Allegations.”

Breakey argues that “meta-arguments,” statements that focus on external features of an argument rather than an argument’s soundness, can be used to critique arguments by pointing out the harm that an argument might cause.

As an example, imagine that somebody tells an armed mob without evidence that grocers are the cause of a crippling food shortage. Pointing out that this argument might cause harm provides an ethical good (the speaker might not make the argument now that they know harm may come of it) and an epistemic good (the argument might be improved or abandoned if the weakness of it is pointed out). While meta-arguments aren’t good or bad by themselves, this example shows how they can be used positively.

However, other times critiques that seem clear to one party in an argument can seem groundless to others. In these cases, meta-arguments can derail discussion rather than clarify it. Worse, it can be impossible to get back on track after these allegations are made.

Big Think reached out to Dr. Breakey, who offered this elaboration on his position:

“When we call out what someone says in an argument as offensive, harmful or unhelpful, it can feel like we are applying an impartial standard. We’re setting down sensible, objective rules within which constructive civil debate can occur. But the reality is that our judgments about such matters are likely to be as controversial and contestable—and, unfortunately, influenced by emotional and cognitive biases—as our views on the original topic of the debate. Reasonable people can disagree on the risks of harm created by speech, the ethical weight that should be given to those harms, where the moral responsibility for those harms properly lies, and how these factors relate to the importance of freely discussing the original topic of the debate. These are all complicated and difficult questions, and will be answered differently by people with different political views and life experiences. As a result, we need to exercise great caution in leveling allegations of harm and offence during an argument. Otherwise, the very differences that led to the original debate—and that make that debate worthwhile—will be used to foreclose it.”

Given these concerns, the essay ends with a call for “argumentational tolerance” that is weary of using meta-argumentative allegations in general, but is open to using them when the speech in question is obviously harmful, such as instances of hate speech or calls to violence.

Should we defend the free speech of everyone — extremists included? | Michael Shermer | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

Another stance is taken by Professor Neil Levy of The Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, in their essay “Why no-platforming is sometimes a justifiable position.”

They agree with many others that free speech is valuable and that good-faith arguments are generally good. However, they find the idea of deplatforming for meta-argumentative reasons more compelling than others might.

In Dr. Levy’s essay, they ask you to imagine that a university has invited a speaker who rejects climate change’s existence to speak on that topic. While that position is bunk, the very act of being invited to speak by a prestigious university grants credence to what the speaker has to say, which cannot easily be refuted by other, better arguments.

Things like being invited to speak by a prestigious school or having seemingly valid credentials can be “higher-order” evidence in favor of their position. Higher-order evidence, Dr. Levy explains, influences how we evaluate arguments. Higher-order evidence in favor of our position can make us more confident in it, while opposing evidence can lead us to moderate our stances.

However, Dr. Levy points out the difficulty of countering higher-order evidence, or the legitimacy it confers, by rational argument alone. They further out the usefulness of attacking the credibility of the speaker’s bunk arguments by focusing not on the argument but on the higher-order evidence’s validity. Here, ad-hominem attacks and meta- argumentative critiques of their speaking at all can remove the higher-order evidence. Deplatforming, often critiqued as the suppression of speech, can also be useful, as it prevents a person from being granted the legitimacy that a speaking invitation can bring.

There is a difference between this position and that of Dr. Breakey. Dr. Levy is more concerned with matters of fact rather than debates over what constitutes acceptable discourse. However, this stance is clearly more open to the idea of using meta-argumental allegations to keep speech non-harmful and productive than other common positions are.

Why being politically correct is using free speech well | Martin Amiswww.youtube.com

Lastly, we have the stance described by the University of Illinois Professor Nicholas Grossman in an essay titled “Free Speech Defenders Don’t Understand the Critique Against Them.”

Professor Grossman considers the current debate around “free speech” and suggests that the debate is really over what we consider socially acceptable these days—a discussion which we’ve had before and will have again.

As he points out, most people would agree that there is nothing wrong with deciding that Holocaust denial is odious. Furthermore, they would likely also agree that private actors can (and should) use their capacities to limit the space available for a Holocaust denier to speak in. Most people would also hardly shed a tear if the denier faced social consequences for their speech. However, not everybody agrees on giving the same treatment to J.K. Rowling in light of her statements concerning transgender individuals.

Professor Grossman argues that our current discussions are really about where the line of “acceptability” is. Are people, like Rowling, crossing that line when they imply transgender women are not women? If so, what social consequences should they face, if any? What else might be on the other side of that line now? How do we know? The line has moved before, consider how common the public use of racial slurs was in the past, is the idea of moving the line now any different?

They agree with Dr. Breakey in thinking that these are big questions without easy answers. However, Professor Grossman suggests that, in determining what speech is socially acceptable, these discussions can, and must, take place for debate to move forward. In contrast, Dr. Breakey suggests that these concerns can derail other debates if not used properly.

Should you defend the free speech rights of neo-Nazis? | Nadine Strossen | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

Perhaps the most obvious take away is that all three of these thinkers agree that certain speakers, notably those inciting violence or those deliberately trying to cause harm using racial slurs, can (and perhaps should) be challenged. It suggests a semblance of agreement exists around the idea that some speech does harm and that this legitimizes certain follow up actions to prevent the speech.

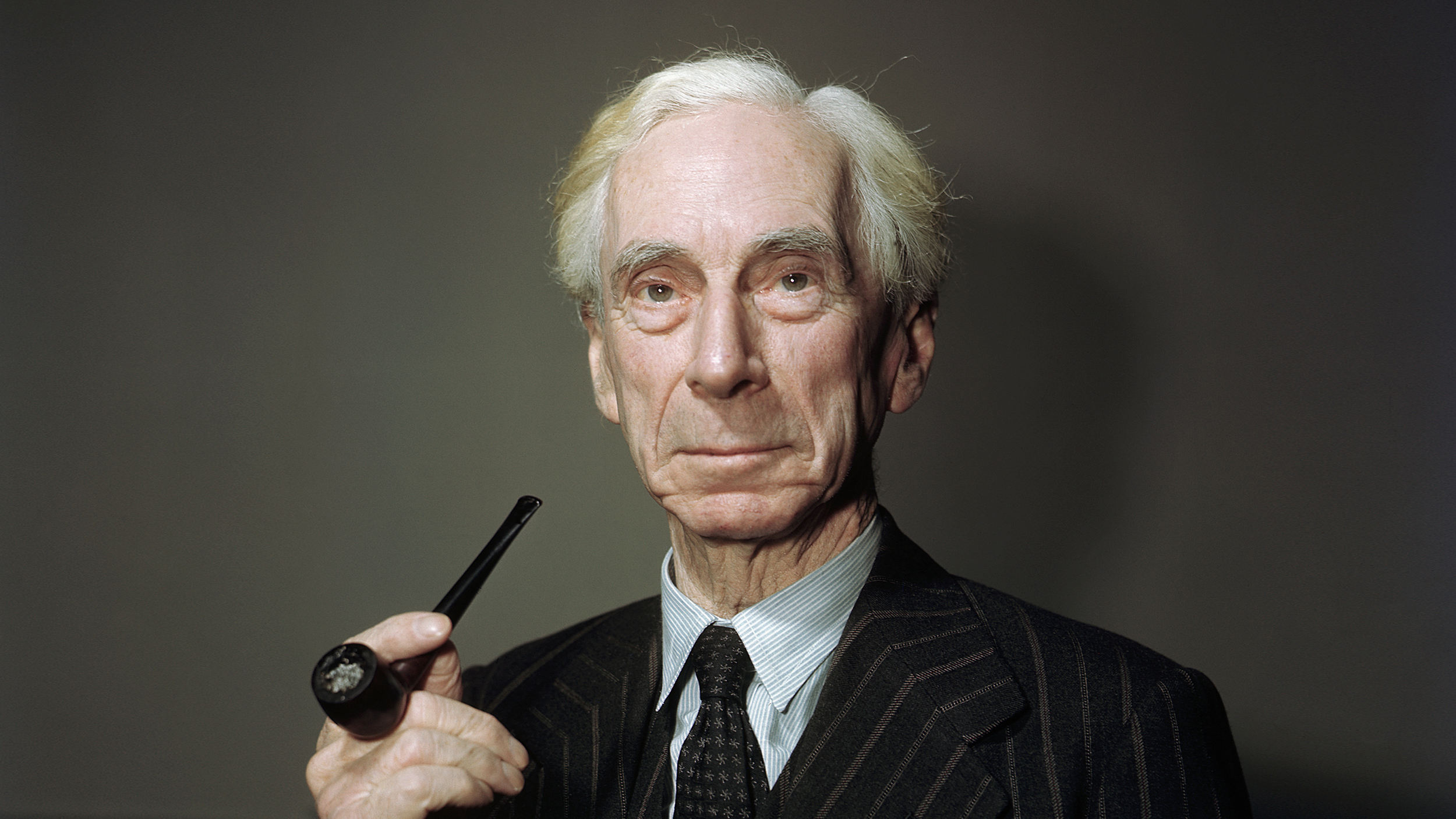

This idea is nothing new; even John Stuart Mill agreed with the idea of censoring speech that could cause immediate violence.

The three thinkers considered here also all agree on the importance of open debate in general. None of them are suggesting that you should be arrested for giving an unpopular opinion. They all argue in favor of using reasoned, respectful debate to advance our understanding of various issues.

However, they disagree on how easy it is to know what is respectful debate and what is speech worthy of critique, deplatforming, and social consequence, and what to do when that line is crossed. While the three do seem to be concerned with slightly different scales, Professor Grossman focuses on societal debates while Dr. Levy focuses on institutional level problems, the differences endure, and each stance can be applied at various scales.

Despite this lack of agreement, they all provide strong arguments for their position and a launchpad for further debate. Though, we might need to already agree on a few points before that debate can even happen.