4 philosophical answers to the meaning of life

- Finding meaning in the face of what can feel like a meaningless universe is a daunting challenge.

- Many philosophical thinkers spent their careers finding a path to a meaningful life.

- While philosophers may disagree on the solution to the problem, they all offer interesting routes to a more meaningful existence.

A common question posed to philosophers and hermit gurus is, “What is the meaning of life?” It’s an important question. Having a sense of purpose in life is associated with positive health outcomes; conversely, not having one can leave a person feeling listless and lost. Friedrich Nietzsche even feared that a lack of meaning would plunge the world toward nihilism, a transition he believed would prove disastrous.

Several philosophers have proposed answers to the age-old question. Here, we will consider four. The list is not exhaustive, however, as many thinkers from many different schools have considered the problem and proposed potential solutions.

Existentialism

Existentialism is an approach to philosophy that focuses on the questions of human existence, including how to live a meaningful life in the face of a meaningless universe. Many thinkers and writers are associated with the movement, including Nietzsche, Simone de Beauvoir, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. But perhaps the most prominent of the 20th-century existentialists was Jean-Paul Sartre.

In Existentialism Is a Humanism, Sartre lays out the fundamentals of the philosophy. He explains, “Man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world — and defines himself afterwards.” In other words, for humans, existence precedes essence. Humans have to decide what it means to be human through their actions and thereby give their lives meaning.

Those choices also define humanity as a whole. As such, Sartre argues that some variation of the categorical imperative — the moral rule that states you should only act in a way that everyone could logically act in — is a vital part of decision-making. Those afraid of existentialists choosing values that would ruin society might also breathe a little easier with this knowledge.

Absurdism

Absurdism is a philosophy created by Sartre’s one-time friend and later intellectual rival Albert Camus. It is based on the idea that existence is fundamentally absurd and cannot be fully understood through reason. It is related to, but not the same as, existentialism.

Camus argues that absurdity arises when humans try to impose order and meaning on an inherently irrational and meaningless world. However, the irrationality of the world and the inevitability of the end of our time in it always come together to mock our best attempts at meaning. This is the struggle we all face.

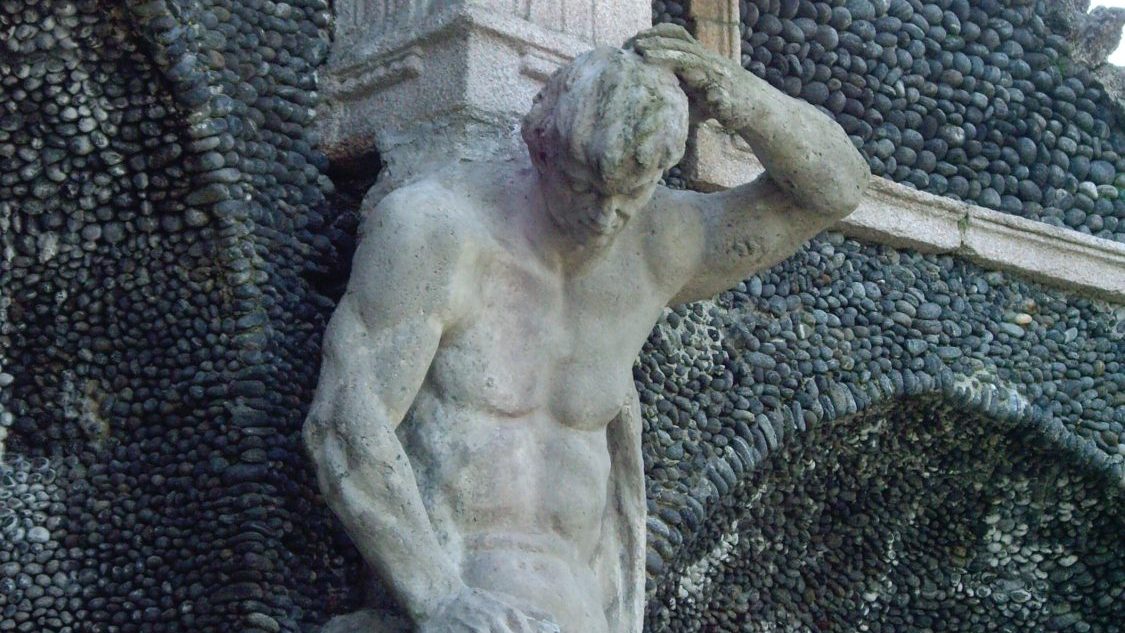

For Camus, the answer lies in embracing the meaninglessness. He points to Sisyphus, the character from Greek mythology who Zeus sentences to push a bolder uphill. Sisyphus can make no progress because whenever he’s near the top, the boulder rolls downhill. His task is ultimately meaningless and must be repeated for all eternity. Despite this, Camus asks us to “imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Like us, he faces an absurd situation with no hope of escape. All the order he imposes on the world will eventually come rolling down again. However, Camus tells us that Sisyphus can rebel against the meaninglessness of the situation by embracing the absurdity. He can assert the value of his life and embrace the meaninglessness of his task. By doing so, he can find meaning in the absurdity — even if his work comes to naught in the end. Sisyphus is Camus’s absurdist hero.

Religious existentialism

While the primary existentialist thinkers were all atheists — Nietzsche raised the alarm on nihilism when he declared “God is dead” — the founder of the school was an extremely religious thinker by the name of Søren Kierkegaard. A Danish philosopher working in the first half of the 19th century, he turned his rather angsty disposition into a major philosophy.

Kierkegaard is concerned with actually living one’s life, not just thinking about it. But in every life, there comes a point where reason runs dry. At that point, passion can help, but Kierkegaard argues that faith is required to really find meaning. That requires a “leap of faith,” and he finds an example of such a leap in the biblical figure of Abraham. As Camus has Sisyphus, so Kierkegaard has Abraham.

In his book Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard argues that Abraham simultaneously knew that sacrificing Isaac was murder, that God was to be obeyed, and that Issac would be alive and well. For his faith and for voluntarily going through with God’s demands, he was rewarded. Abraham embraced the absurd through belief. Rationality was of little use to him, but faith was. In Either/Or, Kierkegaard also praises Diogenes as a “Knight of Faith” who earned the title through more mundane activities.

Buddhism

Another religious take can be found in the works of Japanese philosopher Keiji Nishitani. Nishitani studied early existentialism under Martin Heidegger, himself a leading existentialist thinker, but provided a Zen Buddhist approach to many of the same problems the existentialists addressed.

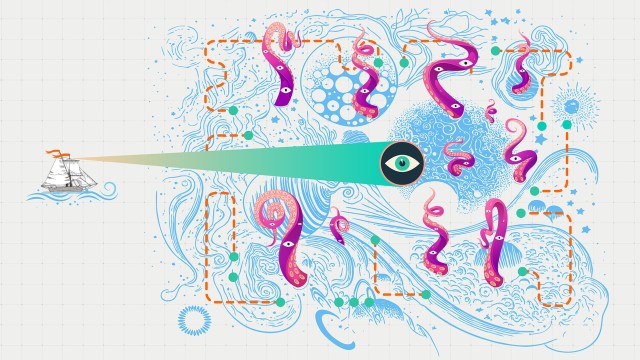

Nishitani saw the modern problem of nihilism as everywhere and tied closely with the tendency for technology to allow us to become more self-centered. While we often encounter “nihility” during major life events like the death of a loved one, it can arise at any time — making the question of how to handle it all the more important.

He describes human life as taking place in three fields: consciousness, nihility, and emptiness (or śūnyatā, as it is often named in Buddhist thought). We live in the first field most of the time, and it is where we get ideas like dualism or that there is a self. However, nearly everyone eventually encounters the nihility and has to face up to the idea of death, meaninglessness, and the void inherent in our ideas. Stopping here is what causes problems. Nishitani argues we must push through to the third field. Emptiness surrounds the other two. It allows the individual to understand the true self, how nihility is just as grounded in emptiness as consciousness, and the interrelation of all beings.

On a more practical level, he suggests Zen meditation as a tool to understand the emptiness inherent in reality. While this is actionable, he does not think it a cure-all to addressing the problem of nihilism as it existed in Japan.