Everyday Philosophy: Is it better to debate people or shrug and drink wine?

- Welcome to Everyday Philosophy, the column where I use insights from the history of philosophy to help you navigate the daily dilemmas of modern life.

- This week, we wonder whether it’s better to withdraw from the world serenely or to take on the world in debate.

- To answer Terry’s question, we look at the Christian tradition of quietism and get to the heart of what philosophy is all about.

The current political climate gives me great angst. I realize that the only way to move forward is for both sides to come together and seek some common ground. However, my morals prevent me from even considering taking the first step. I have written off close friends and even family, and I do not feel much loss over it because my convictions seem so “noble.”

– Terry, US.

I think you might have asked the wrong person, Terry, because if there’s one thing that philosophers really enjoy, it’s having a good old debate. Not an argument — I’ve yet to meet a philosopher who enjoys an argument — but I mean a civil, rational, and attentive dialectic that makes for a good debate. While history gives up a few philosophers like René Descartes who made their living from meditating in a room on their own, the vast majority of philosophy is spent in the seminar room or wandering around an agora, punctuating points with jabbing fingers.

That said, there is something to what you’re asking. Philosophy, at least by some definitions, is about trying to uncover the truth. It’s about unraveling the world’s confusion to find some gleaming, hidden answer. So, if philosophy uncovers the truth — or your “noble” convictions — why bother hurling hot air at each other?

To consider your question more deeply, we’ll first look at the tradition of quietism — the philosophy of withdrawal. It’s a concept that’s always been big in Christian theology but that has also enjoyed occasional and surprising peaks in popularity. Then, in total contrast, we’ll look at the nature of dialectic and the philosophical forum that a lot of philosophers lionize. Then, in a strange twist of events, I’m going to call upon analytic metaphysics to help us out in the final analysis.

Quietism: Leaving the world to get on with it

At its core, quietism means retreating from the active pursuit of truth or intellectual engagement, promoting instead a kind of serene acceptance of the world as it is. Quietism walks the thin line between apathy and calm. It still cares about the world and its people but tends to let everyone go their own way, focusing only on meditation, contemplation, and quietude. Of course, this sounds a lot like monasticism. It’s not surprising, then, that the idea’s roots are found in Christian mysticism, with figures like Meister Eckhart blending quietist retreat with a kind of spiritualism. It meant union with the divine and caring only for prayer. Abandon society in favor of God.

Quietism has never entirely gone away. And what Terry is talking about is a kind of quietism — it’s disengagement from people and withdrawal. The ancient Skeptics in Greece often sought a state of “ataraxia,” which meant a calm acceptance of things. It’s a serenity that comes from shrugging and saying, “Oh well,” to almost everything. The Irish writer Samuel Beckett was known for his quietist leanings. In his 20s, Beckett would have these terrible panic attacks where he’d hyperventilate and wake up in the night drenched in sweat. Quietism is the tranquil withdrawal from things, and it helped Beckett enormously. When you know this fact, you can see quietist strands in his absurdist plays.

So, Terry, you’ve got support from 16th-century Christian theology and one of the greatest writers in history. Quietism would argue that not “even considering taking the first step” to find your common ground is better for your mental well-being. It’s the calm, ataraxic state of the Gallic shrug. Which sounds rather nice with a glass of wine.

Epictetus: Philosophy as a meter stick

In 1687, Pope Innocent XI declared quietism a heresy. While Christianity had enjoyed more than a millennium of monastic tradition, the point of being a Christian was not to withdraw but to engage with the world. It was to convert nonbelievers and save sinners’ souls. When St. Thomas Aquinas devised his five “primary precepts” (or rules) for humans to live by, only one was “worship god.” The others involved living in society, educating children, and reproducing. All of which are hard to do in a hermitage.

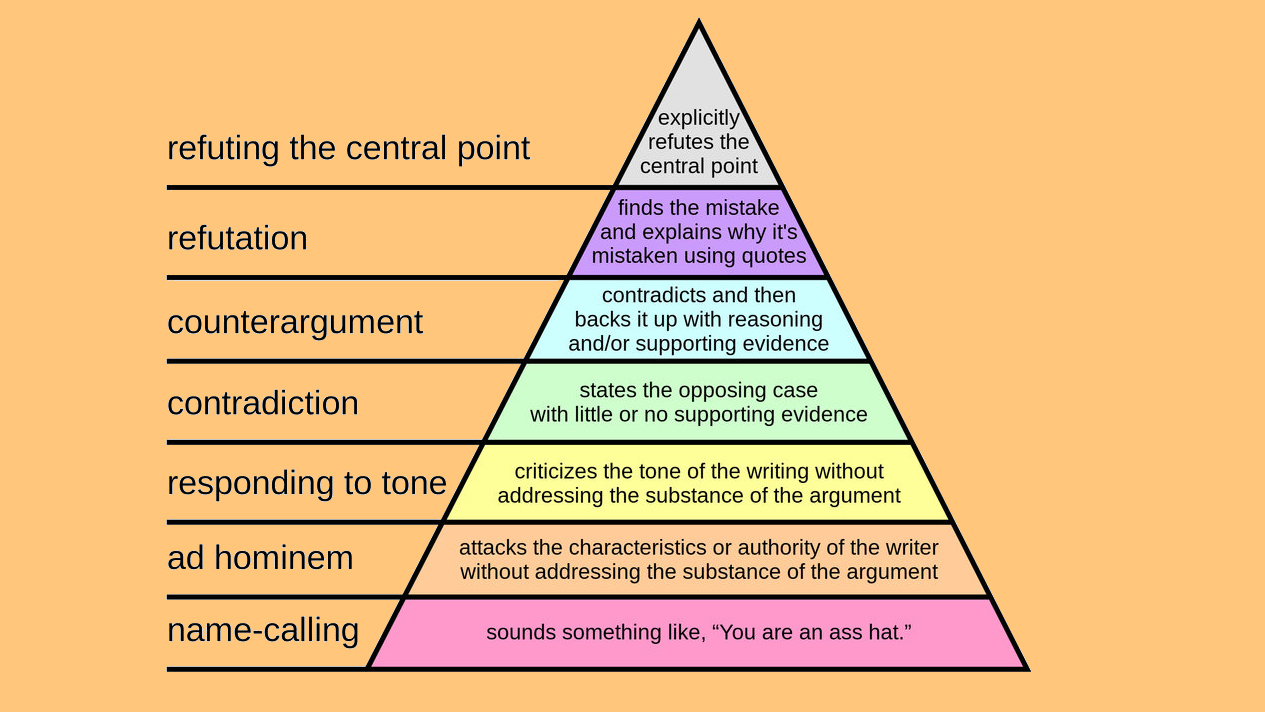

Of course, Terry is not talking about retreating to a cave in some national park and living like Yogi Bear. He’s just talking about not debating certain topics. But even this runs contrary to what most philosophers say. As François de La Rochefoucauld put it, “To try to be wise all on one’s own is sheer folly.” We need to run our ideas by other people to test them. We need to expose ourselves to rival opinions to see if they’re any good. As Epictetus put it, the point of philosophy is to resolve disagreements. Philosophy — rational debate and discussion — is the meter stick or “carpenter’s rule,” which makes straight the crooked and resolves contradictions in what people believe. If we withdraw to our “convictions,” as Terry put it, we’re giving up the game. We’re accepting the possibility of contradiction and allowing “opinion” to muscle out the truth. It might be a philosopher’s fancy, but the entire point of discussing ideas with other people is to clarify those ideas and, we hope, move one step closer to something like the truth.

Your convictions are fine, and you might feel noble, but it is not the philosopher’s quest. Quiestism is a form of capitulation. It’s giving up on working together to improve our ideas.

The potential in all of us

I do get what you’re saying, Terry. I appreciate the vitriol that disguises political discussion today. Bringing up politics at Christmas is sure to ruin the meal, and saying, “I actually think Trump…” will probably be interrupted in some emotionally charged way by someone. When it comes to certain topics, people aren’t ready to philosophize or rationally engage — they’re ready to make a stand, smear their faces in woad paint, and scream some tribal war cry.

But, at the risk of misapplying something that usually concerns only metaphysics, I’ll end by leaning on a quote from the American pragmatist C.S. Peirce. Peirce once wrote that “[philosophy] differs from the special sciences in not confining itself to the reality of existence but also to the reality of potential being.” Peirce was talking about linguistics, epistemology, and possible worlds, but I like to think it can apply, as well, to potential human beings. When we engage with people, it’s easy to engage with the person as they are — the “reality of existence.” But what philosophy can do is engage with the potential of a person. When we discuss ideas with someone, do not see them as they are, but as they might become. See the road they’ve yet to walk. And even, see the road you’ve yet to walk, Terry. Unless something desperate has happened in the week since you emailed me, I doubt you are now about to die. You still have growth in you; you will change and mature.

However calm and appealing the gallic shrug of quietism might seem, I do believe that we have to still engage with other people about almost all matters. This isn’t to say that we should always be looking for a debate, but I think we need to have them sometimes. So, Terry, I think you need to “come together and seek some common ground.”