Everyday Philosophy: Did God save Donald Trump but kill someone else?

- Welcome to Everyday Philosophy, the column where I use insights from the history of philosophy to help you navigate the daily dilemmas of modern life.

- This week we look at whether God can “save” one person while being uninvolved in the death of another.

- To answer the question, we look at David Hume and Richard Swinburne’s discussion of miracles.

Please explain how Trump said “God Almighty” saved him; however, he did not say “God Almighty” killed the gentleman behind him. Can he have it both ways?

– Armour, USA.

When I first received this question and read the word “Trump,” I nearly deleted it within seconds. Big Think doesn’t tend to cover politics, and I am far too lily-livered a character to wade into the charnel-ground warzone that is the American presidential election. But behind Armour’s question — and behind Trump’s comments — is an important philosophical question. It has to do with miracles.

Trump suggested that his narrowly avoided assassination was a miracle. It was an intervention on the part of a divine who wanted the bullet to miss his vital organs. But, as Armour pointed out, does that equally mean that God intervened to shoot the audience member behind Trump? If a miracle is simply an act of God, is it “miraculous” that someone was killed? Or does a miracle imply some kind of positive outcome alone?

To explore the philosophy of miracles, we’re going to look at one of the most famous critics of the concept of divine intervention, David Hume. On the other side — and in favor of the occasional force majeure — we can call upon Richard Swinburne. As usual, I suspect we’ll reach some hugely ambiguous, but mostly educational, conclusion that half answers the question.

David Hume: Never trust a miracle

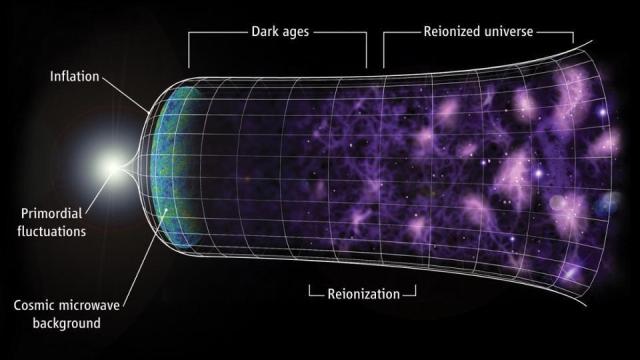

David Hume’s influential 1748 essay “Of Miracles” challenged the idea of miracles being both unreliable and even nonsensical. Hume defines a miracle as a violation of a natural law — something that cannot be explained by normal science. A talking animal, a floating broomstick, and coming back from the dead all break the laws of nature, and so would be considered miracles.

Hume argued that no matter how earnestly someone claimed to experience a miracle — no matter how honestly they think they saw a thing — a miracle will always be based upon inferior evidence when compared with the entire weight of scientific data. Miracles will always be the contradictory and ridiculous testimony of an unreliable witness.

So, while your Auntie Ursula might insist channeling cosmic energy cured her stomach ache, it’s still only one data point set against billions. Given that a miracle must, by definition, go against the grain of all established reason and evidence, David Hume (pre-empting Sherlock Holmes) argued that we must assume any other cause for the miracle, such as confused witnesses or deceitful charlatans.

In the case of Trump, he claimed the bullet was heading for his head or vital organs but that a divine force got involved to nudge the bullet off target. According to Hume, Trump must be either lying or mistaken.

Swinburne: A religious way of seeing the world

The problem with Hume’s account of miracles, as with a lot of attacks on religion more broadly, is that it presupposes an atheistic, godless world before they begin. Hume defines a miracle as a violation of a law of nature, which is fine. It sounds pretty on point. But Hume assumes that the laws of nature are the highest and ultimate cause of all things.

When physicists talk about “fundamental forces” and when scientists talk about the “laws of nature,” they present those as the point at which you can go no further. They are the lowest structure underpinning the Universe on which all is built.

And yet, this is not how the religious believer sees things. It is perfectly justified to suppose that the laws of nature are themselves the product of something else, namely God or gods. So, if God creates and steers the laws of nature, then He could also, quite reasonably, adapt them whenever it suited. As Swinburne puts it: “If there is a God, then whether and for how long and under what circumstances the laws of nature operate depend on God.”

Swinburne gives an analogy. Immanuel Kant was a rigorous, punctual, and predictable creature of habit. He would go for the same walk every day, at the same time, in the same order. There was, to all witnesses, a pattern or “law” to Kant’s walk. Suppose, now, that we also believe Kant to be a compassionate friend, and he hears of his friend’s illness. On this day, Kant’s compassion causes him to violate his own habitual laws. Kant is the ultimate creator of the laws, and so he can, if the moment calls for it, violate them.

To bring the analogy home, God could, if he so wanted, violate the laws of nature because those laws exist by his hand alone. He could even operate within the laws of nature if he wanted to. In the case of Trump, God could, as the final arbiter of these things, simply change the world to suit His ends. He could tip the scales and nudge the bullet. God is not a slave to the Universe.

A different way of seeing the world

The problem that Swinburne points out is that Hume (and many atheists) cannot imagine a worldview or belief structure that places God at the center of everything. Hume begins with and presupposes his atheism (though how atheistic he was is up for debate). Believers, though, do not shuffle God off stage. They do not make God the servant of the laws of nature. The laws of nature, like nature itself, owe themselves entirely to God.

And so, we come back to Trump. Trump is a Christian. And, as a Christian, he believes that God is in control of the Universe and that God, in his omnipotence, can change the Universe as he sees fit. But, now, we risk diluting the concept of a miracle too much in the other direction. If a miracle is “the intervention of God” and “God controls everything,” then everything is a miracle. A lot of Christians do believe that. They see the rising Sun, a baby’s laugh, and a dodged bullet as miracles. Of course, the corollary of that is that blight, depression, and successful assassinations are equally “miracles.” As Monty Python once sang, God created not only “all things bright and beautiful,” but “all things dull and ugly.”

So, as a surprise to no one, we have a kind of half-answer here. If you believe, as Swinburne does, that God is in control of everything — or could control everything — then God has to be both responsible for the missed bullet and the lethal bullet. On the other hand, if you believe that God can or only occasionally wants to intervene, you could claim that God briefly intervened only to save Trump and then “exited” the scene, leaving the laws of physics to resume their natural course, which in this case happened to kill the audience member. But, at least in my experience, this sounds like an unlikely position for monotheists to take.