Dan Carlin on humanity’s uncontrollable “Prometheus complex”

- Dan Carlin, a political commentator and podcast host, spoke with Big Think about humanity’s seemingly unstoppable instinct toward creation.

- The psychoanalyst Gaston Bachelard coined a term that encapsulates this drive: the “Prometheus complex.”

- This complex describes “all those tendencies which impel us to know as much as our fathers, more than our fathers.” How much control we have over this drive remains an open question.

Do not annoy the gods. If there’s one lesson classical mythology teaches us, it’s that you should know your limits and mind yourself. Beware of hubris: the act of boasting arrogance and self-aggrandizement that man pitches against God, the gods, or the forces of nature. It’s sticking a middle finger up at Thor, turning your back on a visiting angel, or trying to steal from Zeus. Hubris is Icarus, of the waxen wings, flying too close to the Sun. But it’s also your friend, Gary, who thought he could drive home in a blizzard.

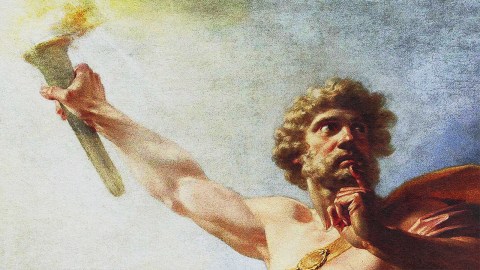

Most people reading classical literature get the point. Stay in your lane. But there is one icon of Greek mythology who didn’t read the memo: Prometheus. Here’s how his story goes:

Zeus was angry at humanity, as he often was, and so took away their capacity to make fire. Prometheus looked down at the shivering, withering people below and took pity on them. Without asking Zeus, he lit a torch from the Sun and smuggled fire back down to Earth. For his treachery and hubris, Prometheus was fastened with unbreakable chains on a mountaintop. Each day, an eagle would gorge on his liver, and every night the liver grew back for fresh torment.

Prometheus ought to be a cautionary tale: Do not mock the gods. But he was instead celebrated and worshiped, eventually becoming the poster boy for the Enlightenment. Prometheus is the righteous rebel who welcomed an eternity of suffering in the name of human advancement. His is the loud and irrepressible voice telling us to innovate, invent, and progress. His very name means “forward thinking.” There are a lot of Prometheans at the moment.

The Prometheus complex

Big Think recently spoke with Dan Carlin, host of the popular podcast Hardcore History and author of the bestseller The End Is Always Near: Apocalyptic Moments. We asked him for his thoughts on the rapid evolution of AI and, more broadly, the history of humanity’s relentless drive to innovate.

“You know, I’ve always been fascinated with this idea about the hubris of the Icarus getting too close to the Sun kind of thing,” Carlin told Big Think. “[I wonder] whether or not human society actually has the agency that we think we have to not invent something if we think it might be bad. If you look down the technological road in the distance and see something horrible, could humankind go, ‘Oh, you know what? We’re just not going to go there.’ I’m not sure we have that agency.”

In the 1930s, the French philosopher and psychoanalyst Gaston Bachelard made a similar point. Bachelard called it the “Prometheus complex.” This is how Bachelard described it:

“To know facts and to make things are needs that we can characterize in themselves without necessarily having to relate them to the will to power. There is in man a veritable will to intellectuality. We underestimate the need to understand… We propose, then, to place together under the name of the Prometheus complex all those tendencies which impel us to know as much as our fathers, more than our fathers, as much as our teachers, more than our teachers.“

The backdoor to knowledge

AI is like a door. We know that behind the door there is a huge, unknown landscape — Narnia through the ChatGPT wardrobe. The question is: What does that landscape look like? The point that Carlin and Bachelard make is not that we aren’t aware of the potential dangers of the future or that we’re not having important conversations about what AI might mean, but that, ultimately, those concerns are beside the point. We possess an impulsive urge, an intellectual twitch, that forces us forward. We will walk through that door and continue developing AI and all sorts of technologies.

This urge doesn’t necessarily stem from a utilitarian position — it’s not that we are necessarily driven toward greater efficiency, socially realistic chatbots, or medical breakthroughs. At the core, it seems the deeper drive is to invent anything that we’re capable of inventing.

Carlin’s point leans on one made by the British science historian James Burke in his TV series Connections. Burke makes the case that all knowledge is connected and that even if we try to avoid this or that because some people think it’s bad, it’s impossible to avoid. All roads lead to progress.

“It’s not possible [to avoid invention], because all knowledge is interconnected like a web,” Carlin told Big Think. “If you walled off a certain part of it because you saw the potential downside, you would get to the same outcome sort of in a roundabout way, right? The connections might not be direct, like saying, ‘Oh, I see nuclear weapons in the distance; let’s go there,’ but we would go through the back door, and eventually we would discover everything around that thing.”

To bring Carlin’s analogy home, we can think about the idea of artificial general intelligence, or AGI. AGI is the point at which AI can perform a wide variety of tasks so competently that it matches or exceeds human intelligence and performance. Some people might see AGI as dangerous. Others may see AGI as the savior of humanity. But while we have debates and conversations, we’re still marching toward AGI. Scientists and programmers behind their computers are solving “everything around that thing.” Our hands and our brains will, perhaps unconsciously, drift toward the very thing we’re debating if we should do.

The Prometheus complex can be seen over and over again in the history of science. It is not simply that Edenic urge to eat the fruit or push the red button. It’s the fact that as the rational, intellectual part of ourselves wrestles with the decision, a deeper, Promethean part of ourselves has pressed it already. Thankfully, it usually turns out okay.