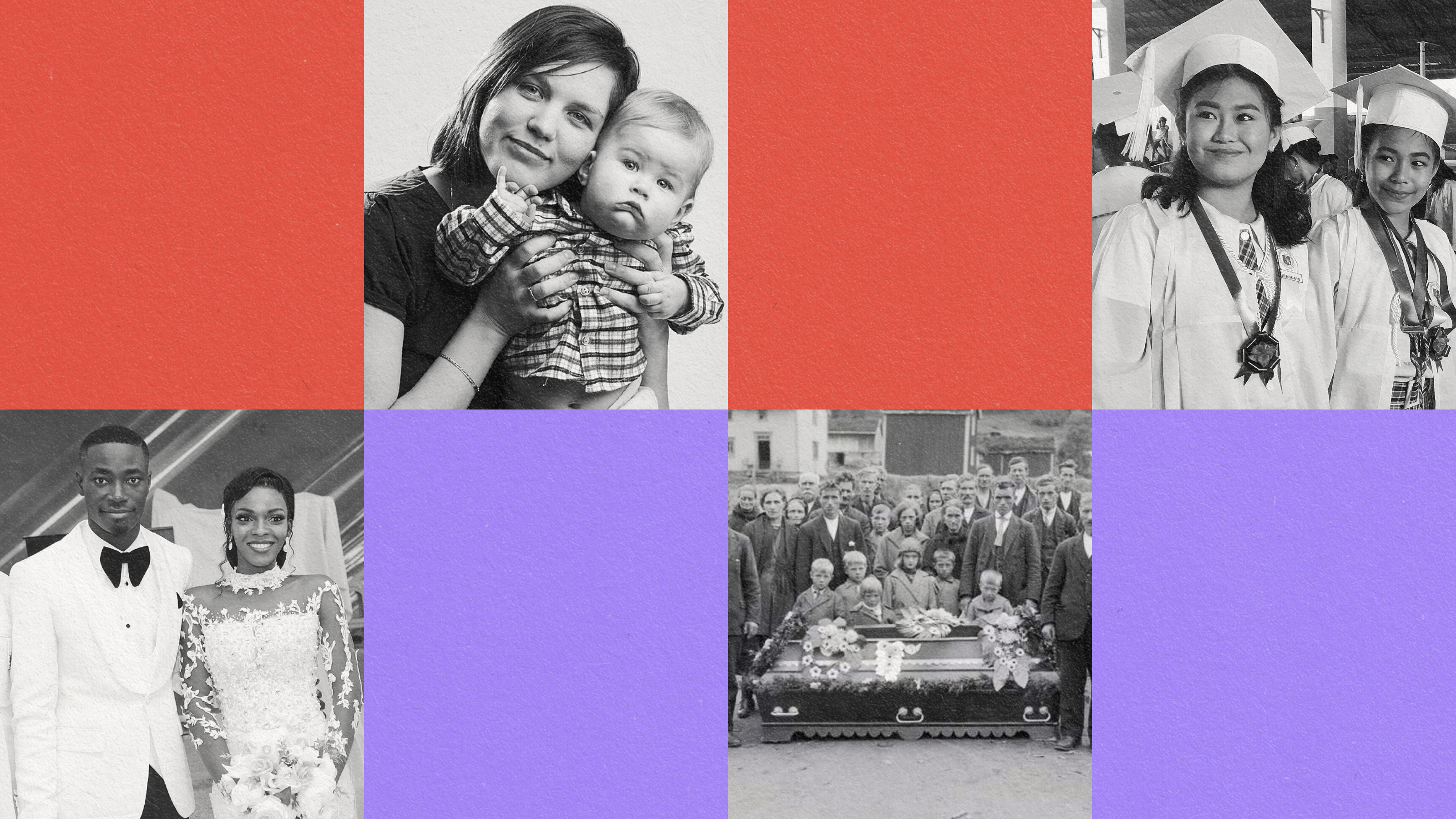

The moral mystery of serial killers with no evident mental illness or trauma

- In August 2023, the UK nurse Lucy Letby was found guilty of murdering babies. She came from a comfortable and loving background.

- Letby opens a debate about the nature of evil: Are evil people made by their environment or born that way?

- Here we look at the two philosophical sides of the debate.

Earlier this month, the face of serial killer Lucy Letby appeared on the front pages of almost all of the UK’s newspapers. Letby is a former nurse who was found guilty of murdering seven babies under her care. She has no known history of abuse, no known underlying mental health conditions, and no known association with extremist groups. By all accounts, she was raised in a normal household in a rich country that afforded her a comfortable middle-class upbringing. And yet she murdered babies.

It’s commonly supposed that people are not born wicked — that our moral propensity for good and evil stems from our upbringing and environment. So how are we to reconcile the existence of evil people who were raised in a caring, nurturing environment? Although the debate over “nature vs. nurture” is far too complex an area to answer here (if we even can answer it), a look at history’s philosophers and sages might shed some light on the issue and teach us where our own intuitions lie.

The four seeds

Broadly, there are two sides to this debate. One says that humans are inherently good but can be led astray by their environments. The other argues that humans are naturally wicked and need their environment to make them — and keep them — good.

A major proponent for the former was the Confucian scholar Mengzi. Mengzi argued that all humans are born with “four beginnings” or “four seeds.” These are virtues such as compassion, shame, respect, and the ability to recognize right from wrong. Like seeds, these natural beginnings want to grow but need a fertile and receptive environment. Mengzi gives a now-common example of saving a child from drowning. He wrote, “If an infant were about to fall into a well, anyone would be upset and concerned.” This concern stems not from selfish reasons but from our natural seed of compassion. Mengzi concludes, “If you did lack concern for the infant, you would not be human.”

Mengzi was one of the first in a long tradition arguing for the perfectibility of mankind. Pelagius, William Godwin, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant all, to some degree, argued the idea that we are inherently good but led astray by society. As Nelson Mandela wrote, “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate.”

Rotten seeds make rotten fruit

Those who argue for the “perfectibility of mankind” are still left with many awkward counterexamples, like Lucy Letby. Mengzi was not so willfully blind to ignore the existence of immoral people, but he supposed it was entirely the result of their upbringing, usually at the hands of some hardship or abuse. And yet, there is nothing obvious in the environment of people like Letby that supports this idea. This was no awful tale of childhood trauma. There was no known PTSD or mental illness.

On the polar opposite side of Mengzi, we have a position most often associated with traditional Christian theology: original sin. While Pelagius (mentioned above) argued against the idea, the overwhelming majority of Church Fathers argued that humans are naturally tempted to sin. Only by following God’s grace and moral stricture can we hope to be good. We need someone who will “lead me not into temptation.”

The Christian idea of original sin worked its way into mainstream European culture, especially within Lutheranism and Calvinism. Asceticism, mental flagellation, and constant guilt are essential if we are to turn back to the good, the thinking goes.

The thrill of evil

In the 18th century, the Marquis de Sade (from whom we get the word “sadism”) argued that most people simply found life boring. The only thing that gives it a thrill is the dark and perverted fantasies we enjoy – fantasies a few, fringe deviants will act upon. For de Sade, we all crave the frisson of the immoral (which is something the Christian Augustine also believed). We love the adrenaline rush of doing something wrong or evil. Life is only exciting when it is punctuated by taboo.

Sigmund Freud didn’t read de Sade as far as we know, but his division of the psyche follows the same tradition. Freud argued that we have primitive drives or impulses (the Id) that tempt us to indulge our animalistic, often savage, selves. The only reason we do not constantly indulge this Id is because of our Superego — an internalized moral code given to us by our culture (usually, our parents).

The open question of evil

The debate about the perfectibility of humankind is an exercise in philosophical confirmation bias. You probably already have intuitions about whether humans are naturally good or evil. And so, you will find examples to support your position. If you believe humans are only ever made monsters by a monstrous upbringing, cases like Lucy Letby pose a challenging question. But if you believe humans are naturally evil, then Letby will be no surprise at all.

To put my cards on the table, I’m inclined to side with Mengzi and Mandela. I find it hard to believe that humans are born evil. And so, I’m rocked a bit by these cases of seemingly random and wanton evil. Answers on a postcard, please. I’d love to hear your thoughts.