I’m “spiritual but not religious.” Here’s what that means for a physicist

- The great physicist Isaac Newton was a strong believer in God, as was essentially everyone in his day. He believed that the motion of the heavenly bodies required “the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being.”

- Just in the last century, scientists have found physical explanations for many phenomena once thought to lie in the province of philosophy or theology.

- Though all things can be explained in terms of atoms and fundamental forces, this does not rob them of their magnificence or meaningfulness.

For many years, my wife and I have spent our summers on an island in Maine. It’s a small island, only about 30 acres in size, and there are no bridges or ferries connecting it to the mainland. Consequently, each of the families who live on the island has their own boat.

My story concerns a particular summer night, in the wee hours, when I had just rounded the south end of the island and was carefully motoring toward my dock. No one was out on the water but me. It was a moonless night and quiet. The only sound I could hear was the soft churning of the engine of my boat. Far from the distracting lights of the mainland, the sky vibrated with stars. Taking a chance, I turned off my running lights, and it got even darker. Then I turned off my engine. I laid down in the boat and looked up.

A very dark night sky seen from the ocean is a mystical experience. After a few minutes, my world had dissolved into that star littered sky. The boat disappeared. My body disappeared. And I found myself falling into infinity. I felt an overwhelming connection to the stars, as if I were part of them. And the vast expanse of time — extending from the far distant past long before I was born and then into the far distant future long after I would die — seemed compressed to a dot. I felt connected not only to the stars but to all of nature, and to the entire cosmos — a merging with something far larger than myself. After a time, I sat up and started the engine again. I had no idea how long I’d been lying there looking up.

Spiritual materialism

I’m a scientist and have always had a scientific view of the world, by which I mean that the Universe is made of material stuff, and only material stuff, and that stuff is governed by a small number of fundamental laws. Every phenomenon has a cause, which originates in the physical Universe. I’m a materialist, not in the sense of seeking happiness in cars and nice clothes, but in the literal sense of the word: the belief that everything is made out of atoms and molecules, and nothing more. No ethereal substances, no psychic energies, no heaven and hell.

Yet, I have transcendent experiences. I felt like I was part of the stars that summer night in Maine. I’ve made eye contact with wild ospreys. I have feelings of being part of things larger than myself. I have a sense of connection to other people and to the world of living things. I appreciate beauty. I have experiences of wonder and awe. Of course, all of us have had similar feelings and moments. While these experiences are not exactly the same, they have sufficient similarity that I’ll gather them together under the heading of “spirituality.”

Thus, I call myself a spiritual materialist. I’m a materialist, as I’ve said, in the sense that I believe that the world is made of material atoms and nothing more. (By material atoms here, I include subatomic particles and the quantifiable energy fields produced by those particles.) At the same time, I acknowledge and embrace the spiritual experiences we all have.

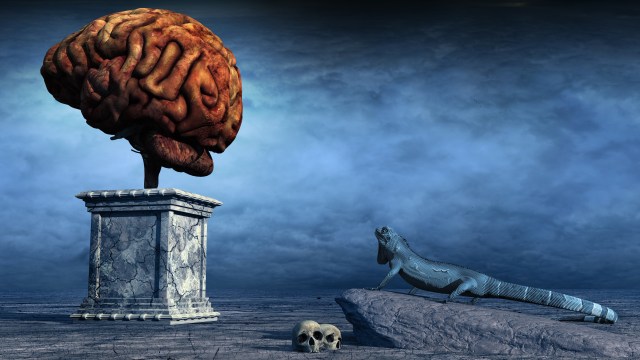

I realize that many people associate spirituality with an all-powerful and all-knowing Being that purposefully created the Universe. I respect those beliefs although I do not share them. I believe that spiritual experiences, as I have defined them, can be explained in terms of a highly evolved brain, which in turn is rooted in material neurons, each of which is a special arrangement of atoms and molecules.

Meaningful matter

Essentially all neuroscientists and most scientists in general believe that the brain and the mind are the same thing. That is, there is no separate, immaterial essence responsible for our thoughts and mental experiences. According to this scientific view, to which I subscribe, all thoughts, emotions, and other mental activities including spiritual feelings are caused by physical processes in the brain — although we still have not filled in all the blanks to get from the material brain to our mental experiences, the most fundamental being consciousness.

By attributing spiritual experiences to a complex of interconnected electrical and chemical activities within the neurons in our brains, I do not mean in the slightest to minimize the magnificence of these experiences. They can be among the most meaningful moments of our lives. The human brain is capable of extraordinary feats, such as creating poetry and music, play, discovering the laws of nature, and conceiving cities and then building them. In fact, our brains, with roughly 100 billion neurons, each of which is connected to a thousand other neurons, are the most complicated objects we know of in the Universe.

Most scientists are materialists. In fact, the vast majority of scientists are sufficiently committed to a materialist view of the world that even if they saw a wheelbarrow suddenly float in the air, they would look for some physical explanation, like a superconducting magnet under the wheelbarrow. If not finding that, they would assume that some new law of nature, yet to be discovered, was at work — but nothing supernatural.

A commitment to materialism

Several years ago, I surveyed a number of scientists to find out how many believed in miracles, defined as events that cannot be explained by scientific rules and laws, either now or in the future. Essentially all the scientists firmly and unequivocally rejected anything “supernatural.” For example, the Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore said to me, “If I could not find any way out of believing that a miracle had occurred would I then believe it to be a miracle? I think the answer is that I would still not believe it to be a miracle, only some outcome that I can’t understand.”

How and why do scientists and the scientifically minded among us make such a strong commitment to a material world, even though we all have the “spiritual” experiences mentioned above? I often trace the beginnings of my own materialist view to my childhood, where I converted a large closet into a laboratory and did experiments there.

One experiment stands out. I read in Popular Science or some other magazine that the time for a pendulum to make a complete swing, called its period, is proportional to the square root of the length of the pendulum. (If you quadruple the length, the period doubles.) What a fascinating rule! But I had to see if it was true. With string and a fishing weight for the bob at the end of the string, I constructed pendulums of various sizes and measured their lengths with a ruler and timed their periods with a stopwatch. The rule was true. And it worked every time, without exception. Using the rule I had personally verified, I could even accurately predict the periods of new pendulums before I built them.

This pendulum law was an amazing discovery for a young kid. There was a profound lesson here: The physical world, or at least this little corner of it, obeyed reliable, logical, quantitative laws. I concluded that nature was material, and that it was orderly. No supernatural or ethereal elements were needed to explain the behavior of things.

I now think that the origins of my materialist worldview must be more complex than the experiments I did as a child. Strict materialism is part of a disbelief in the supernatural, which is related to the powers of God. The great physicist Isaac Newton, who did far more experiments than me, was a strong believer in God, as was essentially everyone in his day. In his masterwork, The Principia, Newton stated that the synchronized performance of moons and planets could never be explained by “mere mechanical causes” but required “the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being.” In particular, as he wrote in his Optics, Newton believed that friction would slowly degrade the motions of planets over time without the active intervention of God. “Some inconsiderable irregularities [in planetary orbits]… will apt to increase till the system wants a reformation” by God. The action of such a Being would, of course, represent a miraculous event. Thus, Newton was not strictly a materialist. He invoked something beyond the physical world to explain behaviors within the physical world.

A waning of religion

Newton’s era and culture were very different from mine. In Newton’s time, little was known about the physical world compared to today. Virtually everyone believed in some form of the supernatural. Virtually everyone believed in God. Religion was much more a part of daily life. In fact, until 1791, the government of the United Kingdom required attendance at the Church of England. By contrast, according to a 2009 study by the Pew Research Center, only 33% of scientists say they believe in God.

Just in the last century, scientists have found physical explanations for many phenomena once thought to lie in the province of philosophy or theology. We understand the nature and causes of many diseases and have developed antibiotics and vaccines to protect us, greatly extending human lifetimes. We have uncovered the instructions (DNA) for creating new life and can actually manipulate those instructions in the lab. We have discovered the energy source of stars and the distances to them. We know the origins of the atoms in our bodies: the nuclear furnaces of stars. We have strong evidence for the origin of our entire Universe, in an extremely hot and dense state called the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago. And for 250 years now, we have known that the planets do not need to be continually spun up by the finger of God to maintain their orbits.

Although there are many things scientists don’t yet understand, we have drawn back the veil on much of the cosmos that was cloaked in mystery and attributed to God in Newton’s day. Even among the general American public, belief in God has decreased from 98% in 1953 to 81% in 2022. Science cannot disprove the existence of the supernatural, but it can impact the reasons for believing in the supernatural.

Conquering the Unknown

This conquering of much of the Unknown has become part of our cultural heritage. This enormous increase in knowledge, which many of us take for granted, has seeped into our view of the world. It has made us more comfortable being in this strange part of the cosmos we find ourselves in, and more confident of our ability to understand the world around us. And I think, as much as the experiments he did, this molded a young boy into a materialist. And now a spiritual materialist.