Why the search for meaning is not a job for science — or religion

- Life is full of paradoxes, and perhaps the best way to approach them is through “poetic realism,” which encourages a sense of wonder and curiosity without the supernatural.

- Many nonbelievers claim that the search for meaning is an individual pursuit. But this is incorrect because meaning is found in our relationships.

- Rituals, art, meditation, and community serve as alternative pathways to finding meaning traditionally served by religion.

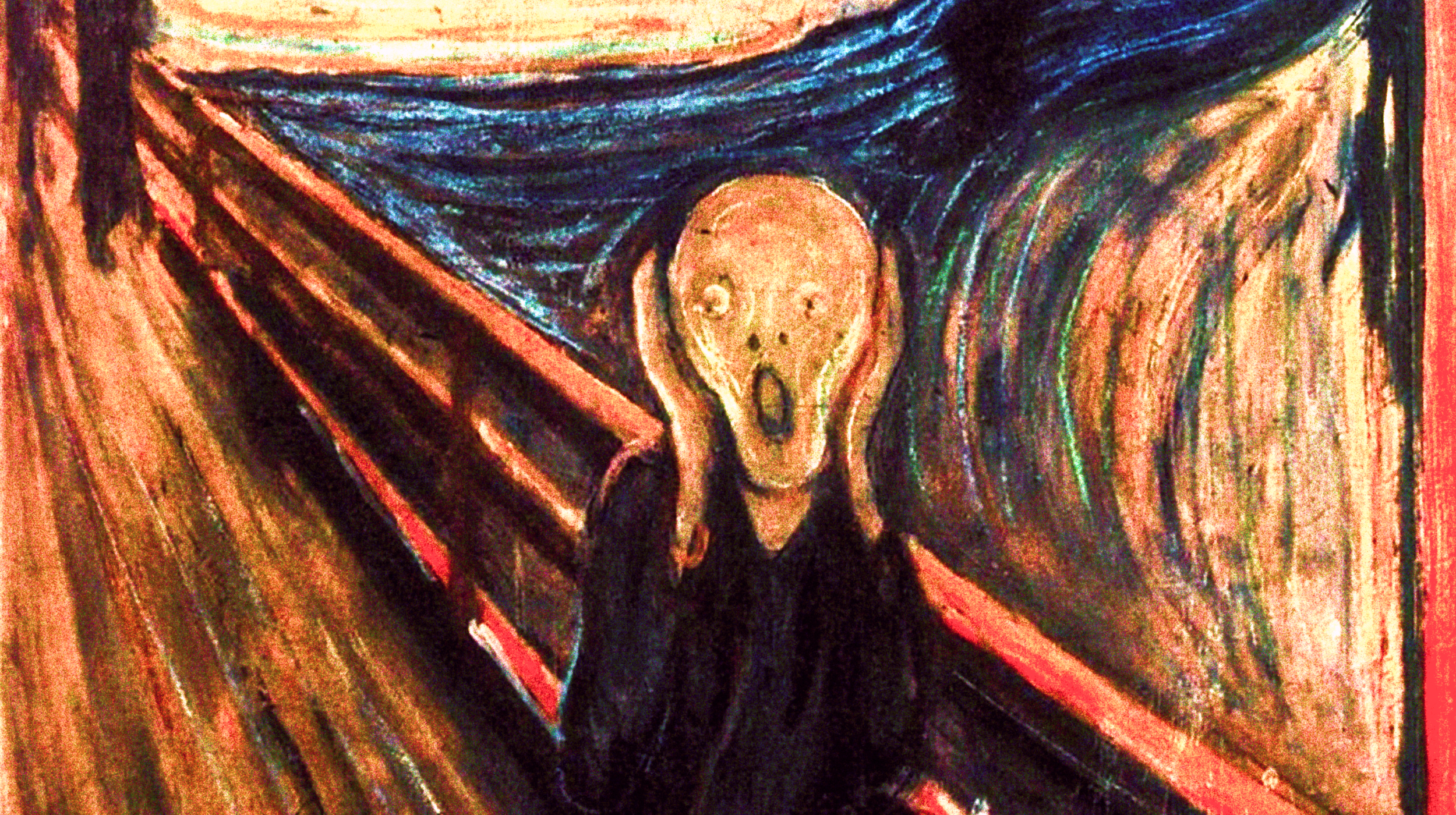

A lot of us are awfully wise and awfully miserable. We are little paradox machines. We want to live forever, but some days seem to go on longer than that. And what is a search for meaning if it cannot reconcile our knowledge of love with our daily experience of it? How about this one: We see that a person can change the world, or use their life for grand adventure, or simply choose what kind of relatively normal life they would like to have — and yet, most of us don’t change the world or go on grand adventures, and many of us have a different life than we had wanted. Here’s one more. We know about change, but we are shocked and unprepared when it happens.

Paradoxes are when two opposing things are true; the two things cancel each other out, yet when you put them side by side and wait for one to prove true and the other false, it doesn’t happen. Because paradoxes are hard to think about, many people manage such difficulties with religious or other supernatural ideas.

The poetry of reality

I think of these questions poetically, without the supernatural. I call myself a poetic realist, by which I specifically mean that I think about the world we have, without the supernatural, but with all the big questions. These big questions aren’t the job of science, but for many human beings, they persist with great reality. So the search for meaning isn’t a job for science. If you are a realist the way I defined it, then the supernaturalism of religion means it isn’t a job for religion either. The addition of ideas outside our natural world, in any search, would be a bad idea.

But where we can’t speak with measurements, and we reject belief in stories that aren’t sensible outside a given culture, we can speak in poetic terms. The inner lives of human beings and their relationships with others and with nature is a world which can be understood poetically with as much flair and fancy, wisdom and depth, mystery and wonder, as any supernatural confection. When I use the word “poetic” I mean no mysticism, just attending to the wonder of the real, which is quite sufficient. For instance, if you think about it, surely consciousness is more astounding than a virgin birth. Poetry helps us meditate on what is both true and amazing, and that can help us live.

I think that for many people, the old jobs of religion get done in the experience of art (making it or taking it in), ritual (sometimes as little as smiling at the tinsel), meditation (quiet time, these days even a moment counts), and community (sometimes you have to leave the house). A little bit of thinking about how these jobs get done can enhance their function for us. It can also help us rethink some ideas that have grown calcified in the world of secular philosophical discussions, over time.

Finding meaning

Whereas many nonbelievers historically and today say that each person must march forth and make their own meaning, I see meaning as relational — or rather I see a correction to be made in that direction. I think it’s useful to think about the ways we exist in webs of meaning.

Rituals and poetry help us feel these connections. Whether we are in the party-throwing times of our lives or not, many of us take hold of the rituals of the year as they go by almost as if they were handrails, landmarks, rewards. The reward is a break from the ordinary, a break from normality, a yearly unusual feast, and costumed visions. It’s interesting to think about what we get from the rituals of the year that we, ourselves, normally take part in, even in the most passive way.

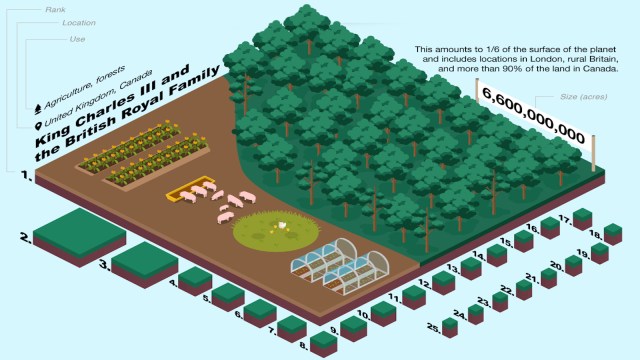

The idea of a meaning of life, as it came down to many of us, is processed through the Christian worldview. The idea of one God who knows everything comes with logical consequences. If there is One God who knows everything, he should know an answer to “Why?” It’s a bit of a historical accident that people ask that odd question. Why should there be a “why” to the big picture? What could the answer be?

The feeling of meaning is sufficient to the definition of meaning. Meaning is what it feels like it is. It’s a roiling mess of too much meaning and too much nonsense and it isn’t coherent, but it isn’t nothing. Like love and morality, we bumble along making a muddle of it, never really knowing what we’ve got our hands on, but meaning is a thing.

Poetically speaking, this seems obvious, but thinking about it can be generative. If something seems worth thinking about, but it’s hard to think about for very long, because it sort of just sits there being problematic, it’s a good time to turn to poetry. Poetry is where people do extended imaginative thinking about slippery paradoxes that evade our attention and take hold of stolid conundrums and shake them until they giggle. Go find any poem you’ve ever sighed at and read it over a few times, and come back to it again and again. I promise it will become a way to sit with the true strangeness of human experience.

If there is a “Why?” it seems right to ask if the ends have been worth the means, given the suffering involved. If there is a “Why?” there’s a moral problem. But what if we reframe the question? What if what matters to us is what matters. Of course there is still meaning — how could taking out an invisible Big Guy change that? Think of something that matters to you, that isn’t all about you, individually. It matters, right? If something matters to you, other than what matters to yourself alone, you’ll find that it holds up to emotional scrutiny. It matters.

On the meaning of life, the story of humanity is as good a reason as God is. If “mystery Sky Guy holds the meaning of all this struggle and pain” was good enough for me once, and it was, I shouldn’t be surprised that it’s good enough for me now to be a part of the story of humanity — as it unfolds, the consciousness and heart of the boundless universe, as I know it. I am lucky and lumping it to be here.

It’s all relational

A key value in this meaningscape is working to know more. Learning about other people and reading books from across history and cultures. If there is one thing I know for sure, it’s that real people (not the ones on shows) are endlessly surprising. There’s a lot that matters that we have in common, yes. But individual people are amazingly odd, as are individual cultures, and the more we know, the less trapped we are. The ways of being that we are stuck in as individuals and as communities are not the only ways of being. No matter how much you find that out, there is always innovation and surprise.

Meaning is relational. Kind of obvious, and yet not. People have been saying for over 100 years that each man makes his own meaning — which is a little true, but really we are born into and enter into networks of meaning, stories half told, feuds and love affairs. Whether we individually think X matters, X may matter very much indeed. Even if you ask yourself what really matters and the answer comes back as “Self!”, how do we advance “Self!”? How do we judge it and know it? Relationally.

Destruction is one of our impulses. Mine too. I like a bit of a shake up in the news, as much as anyone else. But walking that line of refusing and raging on one side, and still being more good than bad, is somehow the job. Anyway, when I read other people say this, it sounds true to me. Write me down on the side of those trying for the good, they say, and I’m moved.

The interfaithless

Writing my new book brought my thinking to new places, or gave me language for things I hadn’t known how to talk about. The title tells you a lot: The Wonder Paradox: Embracing the Weirdness of Existence and the Poetry of Our Lives. For one thing, I speak of the “poetic sacred” most of the time that I use the word “sacred,” but I also show in the book’s introduction that many words that we think of as Christian actually predate the Christian world and meant something civic or natural. The word “sacred” is a key example. Sacred has even come to mean something like “what one holds sacred” in many fields of knowledge and popular conversation. My point of this whole paragraph is to be understood when I say that what is sacred is the striving toward the good.

For me, life can only be understood in poetic terms, and for me it is best lived in poetic terms. Part of what I mean by that is that I join in with the poetic rituals around me — that is, the rituals around me that seem poetic enough to me to be able to feel something for them. When I do, I go ahead and try to feel what I’m being asked to feel, historically. I think about gratitude on Thanksgiving and about my relation to this weird young nation on Independence Day. I’m aware of forgiveness holidays as they go by, and I see reminders of death holidays in my local and worldly world. I try to feel the connection we have with each other, everyone, but especially what I call the interfaithless — those of us at our various old rituals, not believing any of it, but believing in the “inter.”

The truth about this world, in my experience, is that it doesn’t always make sense, or its various senses clash. For me, keeping those paradoxes in my attention, at least sometimes, seems valuable — because they are the truth of our situation, because they are fun and disturbing, because they leave the look of the rest of the world different. They leave the world looking more changeable, both less and more serious, in all the important ways. We are here, and our hearts, we are here together, and then we are gone — and of course it matters.