Smithsonian scientist: I found the 8th wonder of the world in a coffee shop

- Unlike other species, humans possess a unique ability to feel comfortable around strangers.

- This trait likely emerged early in human evolution, allowing the formation of anonymous societies based on markers of identity, such as language or clothing.

- These anonymous societies eventually gave rise to modern civilizations, where diverse populations can coexist and interact peacefully despite superficial differences.

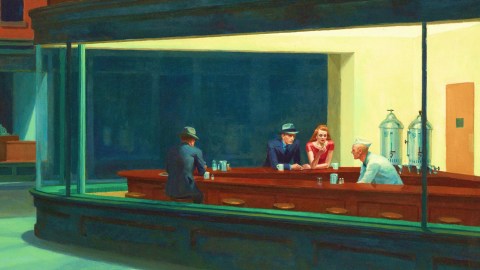

I rank the humble coffee shop as the eighth wonder of the world.

I first realized this some years ago while walking by the other patrons at my neighborhood café, variously chatting, staring raptly at their laptops, or sitting in a morning daze with a cappuccino, as I made my way to the counter where the barista, the only person I knew, gave me a smile.

I had just returned from Africa, where I’d spent two weeks absorbed in the social interactions of animals such as lions, spotted hyenas, and meerkats.

What occurred to me that day was that a coffee shop showcases a miracle inherent in the human brain. That’s not only because my fellow humans have learned to transform the beans of an otherwise uninspiring African shrub into a stimulating beverage, but also because wandering without care past unfamiliar individuals of the same species is a feat no lion, spotted hyena, or meerkat could accomplish. Not even that very close relative of ours, the chimpanzee, can do it. A chimpanzee is incapable of passing an individual it doesn’t recognize on sight without either running away in terror or rushing in for the attack.

That’s not to say outsiders are always enemies. An equally close relation of ours, the bonobo, is far more likely to get along with an unfamiliar individual, but it would still recognize that, merely because that ape is a stranger, it must belong to a foreign group. What’s more, a bonobo would be very unlikely to pass strangers the way people do all the time: casually, and with complete indifference. On the positive side, the bonobo resembles humans in that it doesn’t have the chimpanzee’s knee-jerk reaction of seeing foreigners as dangerous.

These are some of the vertebrates that live in well-defined groups capable of propagating through the generations—in a nutshell, they, like us, have societies. All species with societies divide the world, perennially, into “us” and “them.” But unlike humans, lions, hyenas, and chimps don’t tolerate strangers in their societies. To be socially at ease in their version of the coffee shop—in their den, perhaps—most of these society-dwellers have to recognize each individual they encounter. On top of this capacity for “individual recognition,” they must also keep track of whether that individual is part of their society as opposed to an outsider they have encountered before. Anyone else, any stranger, is without question one of the latter—“them.” (There is a loophole to this rejection of strangers: One may occasionally be accepted if only, especially in a small society, as a new breeding partner, but the transfer process tends to be rocky.)

Society dwelling is relatively rare. Many aggregations that we might casually call “societies” are fluid and ephemeral, such as swarming locusts, or a herd of buffalo. Some individuals in these groups could be socially connected—a buffalo mother with her calf, perhaps. But those present are generally free to come and go, with no clear sense of membership—no sense of us and them.

There’s a strong case to be made that humans have lived in societies from our humble beginnings, even before our lineage separated from that of the chimpanzee and the bonobo. Like humans, both of these apes live in societies, called communities, which means the simplest (and most parsimonious) hypothesis is that the common ancestor of all three species did, as well. That puts the first societies of our ancestors back 7 to 8 million years into our past, at minimum. Ever since that time, life in societies has been as fundamental to human existence as finding a mate or raising a child.

But how and when humans went the extra mile and came to feel comfortable among strangers, like those in my café, is a mystery too little considered. That moment from our remote past was an unheralded turning point. When we no longer needed to know each other on an individual basis is uncertain, but I’d wager the time came early in the evolution of our species, or potentially in the evolution of an earlier ancestor.

How are we able to tolerate strangers in our societies yet still consider ourselves part of a cohesive group? Rather than registering each other exclusively as individuals, we draw on the myriad of clues that each of us presents to the world and that signal who we are. Some of our clues, which I will call “markers of identity,” are quirks that set us apart as unique. Others apply to all manner of affiliations, as when someone sports a crucifix or a chef’s hat. But still others are society-specific, such as our primary language or dialect, or our devotion to a national flag. We don’t wear all of these “markers” on our sleeves. Some are too subtle to register in our thoughts. For example, in one experiment, Americans did surprisingly well at picking out other Americans from Australians based on how they strode or waved a hand in greeting—yet they were surprised to learn of their success and had no clue what differences they were seeing. In the aggregate, this myriad of clues—some obvious, some very subtle—turn each of us into a walking billboard of Who We Are.

Crossing through a café, we take in people’s billboards in the blink of an eye. Before those patrons enter our thoughts—if they do at all—even the most liberal-minded of us have already put them in categories, a process that turns out to be extraordinarily hard to counter in a real, lasting way. Among the categories we register are ethnic and racial distinctions, regardless of whether such groupings have a firm basis. In fact, while the behavior of others influences which groups children come to consider most important, studies show that infants are already lumping people into such categories when they are too young to understand language and be taught about racial groups. Many psychologists focus on our cognitive response to ethnicities and races, which once existed as independent societies that were in the course of history incorporated into our multiethnic nations (from the evidence we have, our cognition handles different nationalities the same way).

Individual-recognition societies, in which only known individuals are considered part of a society, have their limitations. The animals must keep track not just of their personal social networks but of absolutely everyone in the society, whether friend, foe, or individual they don’t care a squat about. This cognitive effort is one likely reason that many animals have societies of just a few dozen—in chimpanzees, up to 200. Taking in others in the abstract based on markers of identity, as we do, in what I call anonymous societies, drastically alleviates this mental work. Adding individuals to a society is no longer a mental burden so long as their identities are consistent (or the members learn to accommodate what variations exist, like the regional accents in the U.S.).

Certain other animals have anonymous societies. For example, sperm whales and pinyon jays use vocalization to mark their society membership, while social insects employ a scent. In extreme cases, such as the Argentine ant that’s invaded much of California and Europe, that odiferous flag holds together colonies that can extend for hundreds of miles and contain billions of individuals.

Utilizing markers can be beneficial for small societies, too, no doubt serving in the remote human past to strengthen people’s bonds and reassure them as to who belonged. For hunter-gatherers, a distant figure could be identified as a fellow tribesperson from say, what they wore, or how they walked, even when they were too far off to identify as Tom, Dick, or Sally. That would have been a relief when people had to be on guard against hostile neighboring groups.

If markers gave societies the potential for growth from the start, what kept them small for so many millennia? Nomad hunter-gatherers had to spread out widely to forage for wild foods. And because people were often out of contact, their markers diverged—then, as now, identities were works in progress, so dialects shifted, and acceptable norms of behavior were updated differently from place to place. Eventually, the differences would cause a social schism, and people would part ways. Each society broke apart before it could reach a population of more than a few thousand.

Tiny as they were by modern standards, those early anonymous societies, held together by markers of identity, nevertheless preadapted us to life in civilizations, which took root when conditions became favorable a few millennia ago. It was then that some societies developed ways to communicate across wide spaces (think horses or roads), thereby syncing up their people’s sense of identity and belonging across far-flung populations. Moreover, with the emergence of strong leaders and laws standards of human behavior—a society’s “markers”—could be readily enforced. The potential was always there, but now, for the first time, societies exploded in size.

Although it happened to be a coffee shop where I came to this realization about our comfort around strangers, this essential human trait is universal to our everyday experiences—one we rely on whether we’re immersing ourselves in a throng at Grand Central Terminal or passing a lone hiker on the Appalachian Trail. Our reliance on markers has yielded a potential flaw in our societies when we perceive ethnic or racial differences as overriding our similarities as citizens, diminishing the sense of equality, and unity, across our societies. It remains a constant struggle across the globe today.

But at the same time, our ease around strangers is what has made possible the blossoming of nations composed of ethnic populations whose commonalities, in a marvel of human cognition, bind people together despite their differences. We are able to sit back comfortably in our coffee shop, surrounded by strangers of splendidly diverse and varied European, Asian, and African ancestry, and recognize each other as fellow citizens.