- Philosophers have been making the controversial claim that free will is an illusion for hundreds of years, but is there proof? Are their conclusions well-founded?

- The idea that humans might not have complete autonomy over their lives brings into question to what extent we do have control. If free will is an illusion, and our control is actually limited, this complicates things like criminal law and social status.

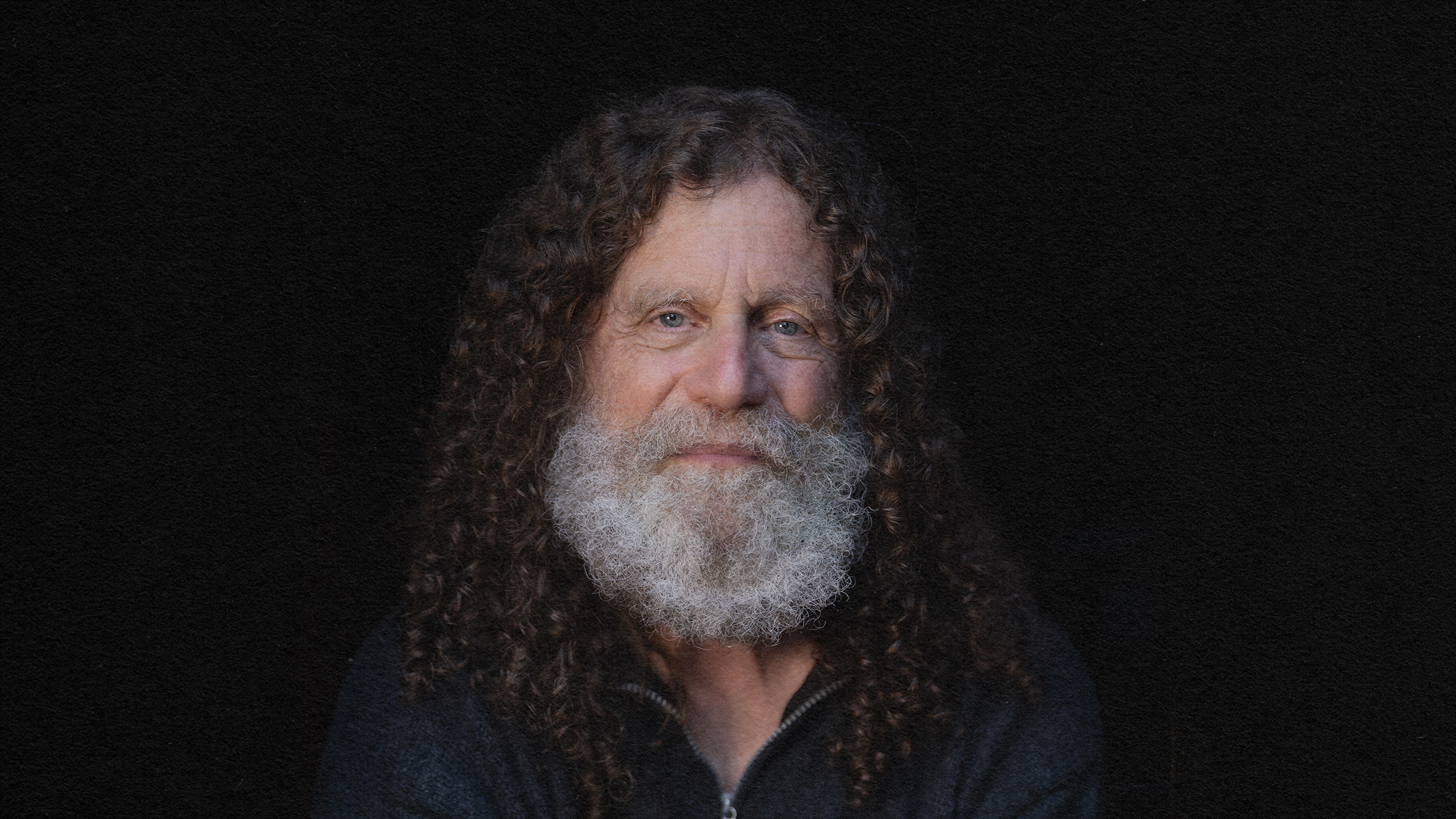

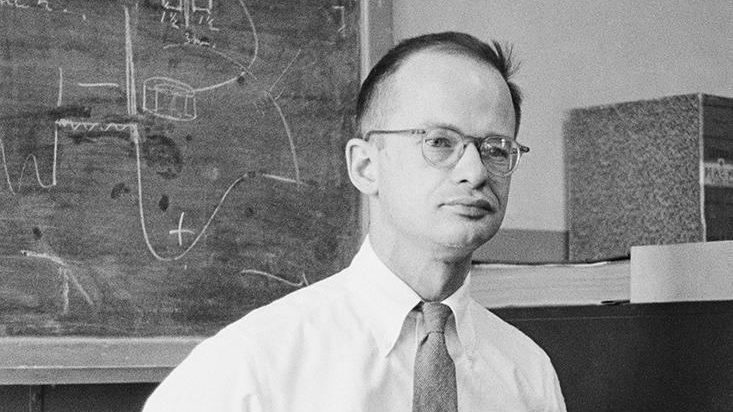

- To advance our collective understanding of free will, Dr. Uri Maoz is leading a collaborative research project that is bringing together neuroscientists and philosophers from around the world. Here’s his take on the age-old debate.

URI MAOZ: We all kind of go around with this feeling that we are the authors of our lives and we are in control, that I could've done otherwise. To what extent is the conscious we are we in control? The subconscious is a force that looms large below the surface of our conscious minds, and it's controlling our lives much more than we're aware. Free will is at the basis of a lot of our social pillars. Our legal system presumes some kind of freedom. There are economic theories that assume that people are free to make their decisions. So for all those things, understanding how free we are, the limits of our freedom, how easy it is to manipulate our freedom and so on I think is important. If we understand the interplay between conscious and unconscious, it might help us realize what we can control and what we can't.

My name is Uri Maoz, I study how the brain enables things like consciousness and free will.

NARRATOR: Okay, Uri, what is free will?

MAOZ: Sure, that's easy. Generally, humans have a sense that they control themselves and sometimes their environment more than they do. You don't try to control every contraction of every muscle in your hand. And if you did try (laughs) to control that, well good luck to you because if you try to concentrate exactly on how it is that you're walking, it's even hard to walk. So there are certain places in the brain that if you stimulate there a person begins to laugh. You ask them, "Wait, why are you laughing?" And they say, "Oh, I just remembered this really funny joke." The brain kind of puts together some reasons for something that you did while we thing they are under our full conscious control they are not.

There is a famous experiment made in the early 80s by Benjamin Libet. The idea is that a person is holding their hand and they're told whenever they have the urge to do so, you flex whenever you want. However at the same time, there is this rotating dot on the screen and your job is to look at the screen and say where the dot was when you first had the urge to move. So then you have this weird situation, only 200 milliseconds before you move do people say, "I'm aware that I've decided to move." But if you look into their brain, you can see something there a second before they do. So what happens in that interval? So kind of nefarious neuroscientist that would an electrode on you would say, "Aha, you're about to move now." But you would not be conscious of it, and some people interpret it [inaudible] experiment to suggest that all of these big important life decisions are maybe unconscious.

Libet's experiment proved controversial, but inspired subsequent tests. Dr. Maoz's own research attempted to observed the brain signals Libet measured in real time by directly monitoring the brain of epilepsy patients. We approach some of these patients and we say, "Would you please play something like, uh, two choice version of rock, paper, scissors? At the go signal we each raise a hand and, let's say, if we raise the same hand, I win, if we raise different hands you win." We had a system that was processing the whole thing in real time, and just before we got the go signal, I got a beep in my earphones telling me which hand to raise so I would beat the subject. We could predict them about 80% of the time. Even if we, let's say, we don't have as much free will about raising my right or my left hand right now, to some extent who cares? It's just, I mean, nobody's gonna take you to court because you raise your right hand and not your left hand for no reason and for no purpose.

Now let's say that I say to you, there's a burning car and you have to decide whether to run in and try to save your friend or not, okay, now you're making a decision that matters. So how do you take control back from you subconscious? The trick may be found in a fable Ulysses, the ancient Greek warrior who while sailing home was told about the sirens. The sirens were monsters posing as beautiful women who would sing to passing ships hoping to lure them closer and ultimately to their death. Ulysses was warned of the sirens ahead of time and knew that his subconscious would be unable to resist the siren songs. So Ulysses made a conscious decision ahead of time to have his crew fill their ears with beeswax and tie him to the mast. Ulysses and his crew sailed past the sirens unharmed.

You could think about this as a struggle between like the later unconscious and current conscious because later on I will not be in a position to control myself in the way that I want it. Neuroscience is a newcomer to the field of free will. What are exactly the kind of questions that are worth asking? What different kinds of experiments that can say something about conscious and unconscious decisions could help us be more modest in what we realize we can control and what we can't, and then also be a bit more forgiving towards ourselves about our decisions and our actions? Not everything is within our control as much as we would think or maybe even would wish. Do I have free will depends, of course, on the definition. In the sense that the world could go one way or another way depending on my decision, no, I don't think I have that power. But to the extent that I can act according to my desires and my wishes, yes, I- I think I can. I wish to be here and here I am.

NARRATOR: To learn more about challenging ideas like this, visit us at templeton.org/bigquestions.