South African city to seize private land without paying in ‘test case’

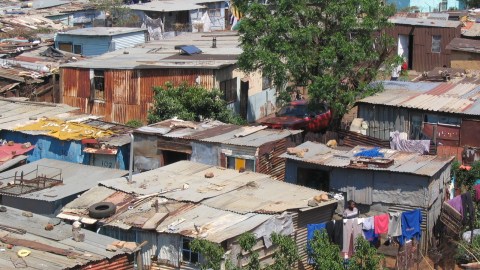

An informal settlement in Johannesburg (Photo: Matt-80)

- Since the end of apartheid, South Africa has seized private land from citizens but always compensated owners.

- The new proposal is a more radical approach to correcting apartheid-era inequality.

- However, South Africa’s constitution still requires the government to compensate land owners, so it’s unclear how the government’s seizure of private property without pay would play out in courts.

A city in South Africa is preparing to seize land from private owners, without paying, to build low-cost housing.

The solution is meant to correct historic injustices and address dire land and housing shortages in Ekurhuleni, a city located outside of Johannesburg where about 600,000 of its 4 million residents live in “informal settlements.” Ekurhuleni’s executive mayor, Mzwandile Masina, said these dwellings are “horrible for human beings,” and that land expropriation would serve as a “test case” for the nation, which is struggling with stark wealth inequality.

“Our policy is not to take the land by force,” Masina told The Associated Press. “Our policy is to make sure the land is shared amongst those that need it.”

Since the end of apartheid in 1994, most of South Africa’s private land, farms and estates have been owned by white citizens even though they comprise just 8 percent of the population. In 1994, South Africa passed an amendment that allowed the government to expropriate land as long as it’s “for a public purpose and with the payment of compensation.”

However, the ruling African National Congress suggested in 2017 that “expropriation without compensation” should be a legal tool the government can use to redistribute land, even though the constitution still includes the compensation clause.

A “test case” for South Africa

Masina said he expects landowners to sue the government once the municipality moves ahead with the seizing of property. His hope is that the case will force a ruling on whether landowners must be compensated when their land is expropriated. Still, it’s unclear how the case would play out, especially considering the ANC has promised “radical economic transformation.”

“In any country, the majority of the population must play a key role in the economy,” said former President Jacob Zuma in 2017. “In South Africa, this has not happened due to the legacy of apartheid that many still choose to deny.”

In February, Zuma was replaced by Cyril Ramaphosa, who argued for expropriation without compensation in an article published in London’s Financial Times.

“This is no land grab; nor is it an assault on the private ownership of property. The ANC has been clear that its land reform programme should not undermine future investment in the economy or damage agricultural production and food security,” he wrote. “The proposals will not erode property rights, but will instead ensure that the rights of all South Africans, and not just those who currently own land, are strengthened. SA has learnt from the experiences of other countries, both from what has worked and what has not, and will not make the same mistakes that others have made.”

Still, the ANC has yet to pass an amendment guaranteeing the constitutionality of expropriation without compensation.

“You can’t guarantee the outcome,” Ben Cousins, research chair in poverty, land and agrarian studies at the University of Western Cape, told The Associated Press. “The court may find you do have to pay some level of compensation. It could backfire quite badly.”