In ‘The Queen’s Gambit’ and beyond, chess holds up a mirror to life

Netflix

If this use of chess to represent life feels familiar, it is largely thanks to the medieval world.

As I argue in my book “Power Play: The Literature and Politics of Chess in the Late Middle Ages,” the game’s early European players turned the game into an allegory for society and changed it to mirror their world. Since then, poets and writers have used it as an allegory for love, duty, conflict and accomplishment.

The game’s medieval roots

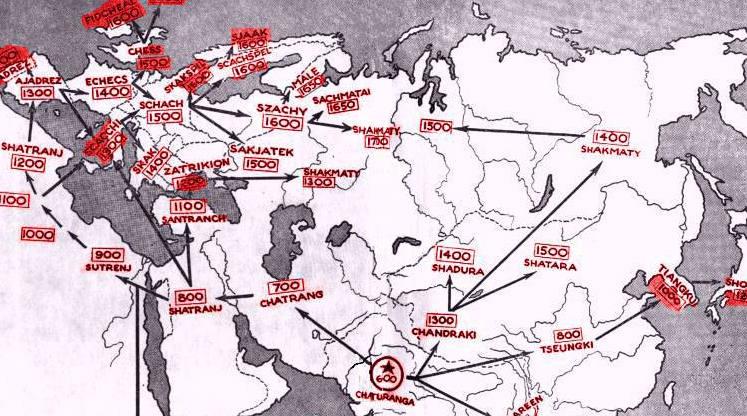

When chess arrived in Europe through Mediterranean trade routes of the 10th century, players altered the game to reflect their society’s political structure.

In its original form, chess was a game of war with pieces representing different military units: horsemen, elephant-riding fighters, charioteers and infantry. These armed units protected the “shah,” or king, and his counselor, the “firz,” in the game’s imagined battle.

But Europeans quickly transformed the “shah” to a king, the “vizier” to the queen, the “elephants” to bishops, the “horses” to knights, the “chariots” to castles and the “foot soldiers” to pawns. With these changes, the two sides of the board no longer represented the units in an army; they now stood in for Western social order.

The game gave concrete expression to the medieval worldview that every person had a designated place. Moreover, it revised and improved the very common “three-estate” model: those who fought (knights), those who prayed (clergy) and those who worked (the rest).

Then there was the transformation of the queen. Although chess rules across medieval Europe had some variations, most initially granted the queen the power to move only one square. This changed in the 15th century, when the chess queen gained unlimited movement in any direction.

Most players would agree that this change made the game faster and more interesting to play. But also, and as the late Stanford historian Marylin Yalom argued in “The Birth of the Chess Queen,” the queen’s elevation to the strongest piece appeared first in Spain during the time when the powerful Queen Isabella held the throne.

A ‘mating’ dance

With a powerful female figure now on the board, jokes about “mating” abounded, and poets often used chess as a metaphor for sex.

Take the 13th-century epic poem “Huon de Bordeaux.” Wanting to expose his newly hired servant, Huon, as a nobleman, King Yvoryn urges him to play chess against his prodigiously talented daughter.

“If thou can mate her,” Yvoryn says, “I promise that thou shalt have her one night in thy bed, to do with her at thy pleasure.” If Huon loses, Yvoryn will kill him.

Huon does not play chess well. But this turns out not to matter because he looks like a medieval version of “Queen’s Gambit” breakout star Jacob Fortune-Lloyd. Dizzy with desire and desperate to sleep with this heartthrob, Yvoryn’s daughter plays badly and loses the game.

In the 14th-century poem “The Avowyng of King Arthur,” chess also stands in for sex. At one key moment, King Arthur summons a noble lady to play chess; together they “sat themselves together on the side of the bed” and “began to play until dawn that was day.” The repeated “mating” on the board not-so-subtly hints at a night of lovemaking.

It also shows up to this end in “The Queen’s Gambit.” In an echo of Huon’s game, Beth plays with her friend and love interest, Townes, in his hotel room. Their match, however, is interrupted when it becomes clear that Townes doesn’t share Beth’s feelings. Later in the story, Beth plays with Harry Beltik. Their first kiss takes place over the board and prefaces their sexual consummation.

Chess as ‘life in miniature’

But much deeper and more interesting are the medieval allegories that use chess to reinforce societal obligations and ties between citizens.

No author did this more comprehensively than 13th-century Dominican friar Jacobus de Cessolis. In his treatise “The Book of the Morals of Men and the Duties of Nobles and Commoners on the Game of Chess,” Jacobus imagines chess as a way to teach personal accountability.

In four short sections, Jacobus moves through the gameplay and pieces, describing the ways each one contributes to a harmonious social order. He goes so far as to distinguish pawns by trade and to connect each to its “royal” partner. The first pawn is a farmer who is tied to the castle because he provides food to the kingdom. The second pawn is a blacksmith, who makes armor for the knight. The third is an attorney, who helps the bishop with legal matters. And so on.

Jacobus’ work became one of the most popular of the Middle Ages and, according to chess historian H.J.R. Murray, at one point rivaled the number of Bible copies in circulation. Even though Jacobus in his prologue implies that his book is most useful for a king, the rest of his treatise makes clear that all people – and the piece they most closely resemble – can benefit by reading his work, learning the game and mastering the lessons that come with it.

Jacobus’ allegory becomes one of the central messages of “The Queen’s Gambit.” Beth reaches her full potential only after she learns to collaborate with other players. Just like the pawn she converts in her final game, Beth becomes a figurative queen only with the help of others.

But this is not the only modern work that deploys chess in this fashion. “Star Wars,” “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” and “Blade Runner,” to name just a few, use versions of the game at key moments to show a character’s growth or to stand in as a metaphor for conflict.

So the next time you see a headline like “Trump Nears Checkmate” and “Gang of 10: Obama’s Checkmate,” or see an ad for a “Checkmate” infidelity test, you can thank – or curse – the medieval world.

Grandmaster Garry Kasparov’s observation ultimately holds true. “Chess,” he once quipped, “is life in miniature.”

Jenny Adams, Associate Professor of English, University of Massachusetts Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.