Why journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov won the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize

- Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Ressa investigates the abuses of power by Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, while Muratov covers corruption in Russia.

- A free and open press is essential to democracy and freedom. Without journalists like Ressa and Muratov, the world would be a darker place.

Would you risk your life to uncover the truth? To hold corrupt authorities accountable, would you be willing to die and endanger the lives of everyone you hold dear? Do you think you’d have the courage to publish a story if it meant years of prison and torture? Odds are that few would.

That’s why the recipients of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize — Maria Ressa, from the Philippines, and Dmitry Muratov, from Russia — are such fitting choices. At the ceremony on October 8, the Nobel Committee praised the two journalists for “their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace.” Brave and principled in the face of unrestrained authority, they both deserve the Nobel Peace Prize and their stories should be heard.

Maria Ressa and Duterte

In 2016, the Philippines fairly and democratically elected one of the most controversial populist leaders in the world: Rodrigo Duterte. Before he was even elected, Duterte made little effort to hide who he was. In fact, it likely won him the presidency.

In April 2016, he made horrific comments surrounding the rape of Australian minister, Jacqueline Hamill, which he later referred to as “how men talk.” Although he later apologized, it was a repulsive thing to say from a man who confessed to sexual assault in his youth.

Duterte campaigned on a pledge to kill every drug dealer. He said, “Forget the laws on human rights. If I make it to the presidential palace, I will do just what I did as mayor…I’d kill you. I’ll dump all of you in Manila bay and fatten all the fish there.” In a 2015 interview with Laureate Maria Ressa, he said, “I killed about three of them…I don’t know how many bullets went from my gun inside their bodies. It happened, I cannot lie about it.”

Duterte was a self-confessed sex offender and murderer — a man who campaigned on a message of violence and power. So, it took incredible fortitude for Maria Ressa and her media company, Rappler, to question, investigate, and challenge his authority. Ressa has consistently called out Duterte’s murderous anti-drug policy, which is mostly carried out by extrajudicial “death squads,” such as the “DDS” — or Davao Death Squad. After Filipino Senator Leila de Lima challenged Duterte on his past murders in 2016, and on his brutality, she was arrested not long afterward on spurious corruptions charges. The European Parliament stated that it thought her charges were “almost entirely fabricated.” She remains in prison.

Maria Ressa is not, yet. Although she has been arrested several times on dubious grounds (ostensibly relating to bizarre cyber libel laws), Ressa continues her work. Her commitment to investigative work and accountability journalism is dangerous and difficult. In an interview with NPR, Ressa said, “when you don’t have facts, your democracy becomes untenable.” She said activists and opposition are often “pounded into silence” by authorities who exploit media to dishonest ends. She won’t be pounded down.

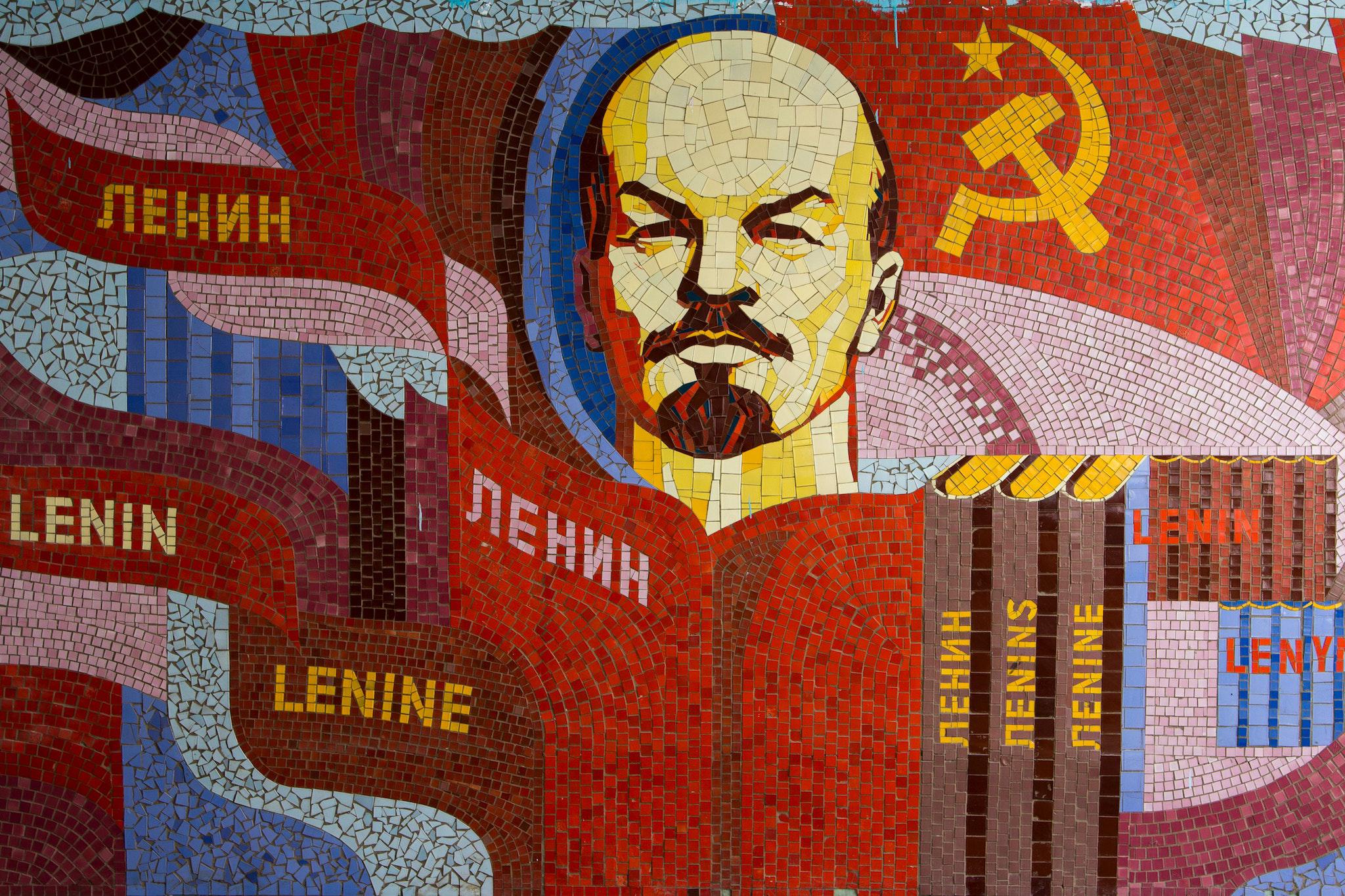

Dmitry Muratov and Novaja Gazeta

It will hardly come as a surprise to hear that Russia has a murky past when it comes to the free press. The government comes down hard on journalists and media outlets that consistently call out the Putin administration. Most of this is done behind the smokescreen of plausible deniability, with pearl-clutching press conferences portraying Russia as innocent bystanders. From the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko to the attack on Malaysia Airlines Boeing 777 to the appearance of “little green men” in Ukraine, the Russian government has a long history of flouting its own laws and international laws. The nation’s approach to journalists is no different.

The journalist Irina Slavina committed suicide by self-immolation in front of a government building, an act of protest after she was bankrupted by legal proceedings and harassed for months. Dmitry Popkov was shot and killed after investigating police corruption. Maksim Borodin, who had been investigating crime and corruption, died from apparently jumping out of a window. Natalia Estemirova was shot in the head after calling out Russian security tactics in Chechnya. Opposition members like Boris Nemtsov and Boris Berezovsky both wound up dead, while Alexei Navalny was first poisoned by a nerve agent, and now languishes in jail.

Whether these killings were the work of the Russian government will probably never be proven. But they show that it’s dangerous business to question and challenge authority in Russia. Laureate Dmitry Muratov knows this more than anyone. Since he founded his media company, Novaja Gazeta, six of its employees and journalists have been murdered. It regularly covers police corruption, security forces use of brutality, electoral fraud, and human rights violations. As the Nobel Committee wrote, “The newspaper’s fact-based journalism and professional integrity have made it an important source of information on censurable aspects of Russian society rarely mentioned by other media” despite constant “harassment, threats, violence and murder.”

The Importance of Free Media

I suspect that few people, myself included, would have the courage to do even a fraction of what Dmitry Muratov and Maria Ressa do. Many people find it hard to speak up against their bosses at work in their law-abiding, Western and liberal countries, let alone stand against authority in the Philippines or Russia.

For a moment, try to put yourself in Maria Ressa or Dmitry Muratov’s shoes: Every day you live with the real possibility of murder. Ressa mentioned how she would wear a bullet proof vest every day. Paranoia is not paranoia if it is grounded in evidence.

Journalistic work like theirs is invaluable to democracy, freedom, and human rights. When Maria Ressa says that democracies become untenable without access to factual information, she’s absolutely right. Since media was invented, propaganda and obfuscation have been the hallmarks of totalitarianism and dictators. When we don’t know the facts or the reality of the situation, how can we hope to make informed decisions, or call authority to account? The “Fourth Estate” of the press, as well as the “Fifth Estate” of online activists and investigators, helps give life to the freedoms we have today. By shining light on the darkest parts of government, and by asking questions when others are too scared to ask, journalists like Maria Ressa and Dimitry Muratov are handing power to us: the people.

That is why their recognition and award of the Nobel Peace Prize is well deserved.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.