Microplastic overload: Is cutting production the only realistic way to curb pollution?

- Microplastics have been detected everywhere — from the ocean floor to the human brain — raising serious concerns about health and environmental impacts.

- While some advocates and researchers push for systemic solutions like production caps to curb plastic pollution, opponents argue that these measures could harm economies and shift plastic production to countries with lower environmental standards.

- Both sides agree that addressing the issue requires international cooperation, but debates over solutions reflect the tension between economic interests and environmental urgency.

A few days into researching microplastic pollution, a friend asked me how my article was coming along.

“I threw out my plastic cutting board and have been scrolling through $250, 10-gallon stainless steel water jugs on Amazon for the past hour,” I admitted. After all, making probably meaningless purchases was the only way that I, a 33-year-old core millennial, know how to cope with my eco-anxiety.

Her response? A flood of Instagram memes. One of them was particularly strong: it compared humanity’s exposure to toxins with a classic Pokémon evolution. Asbestos was Charmander, lead poisoning was Charmeleon, and microplastics? Charizard — the final form, a fully evolved nightmare of environmental contamination. Another meme read: “The microplastics in me honor the microplastics in you.”

I laughed — because, honestly, what else can you do? Still, beneath the humor is a familiar kind of dreadful resignation — a type of gallows humor: We’re screwed; we might as well laugh about it.

Microplastics

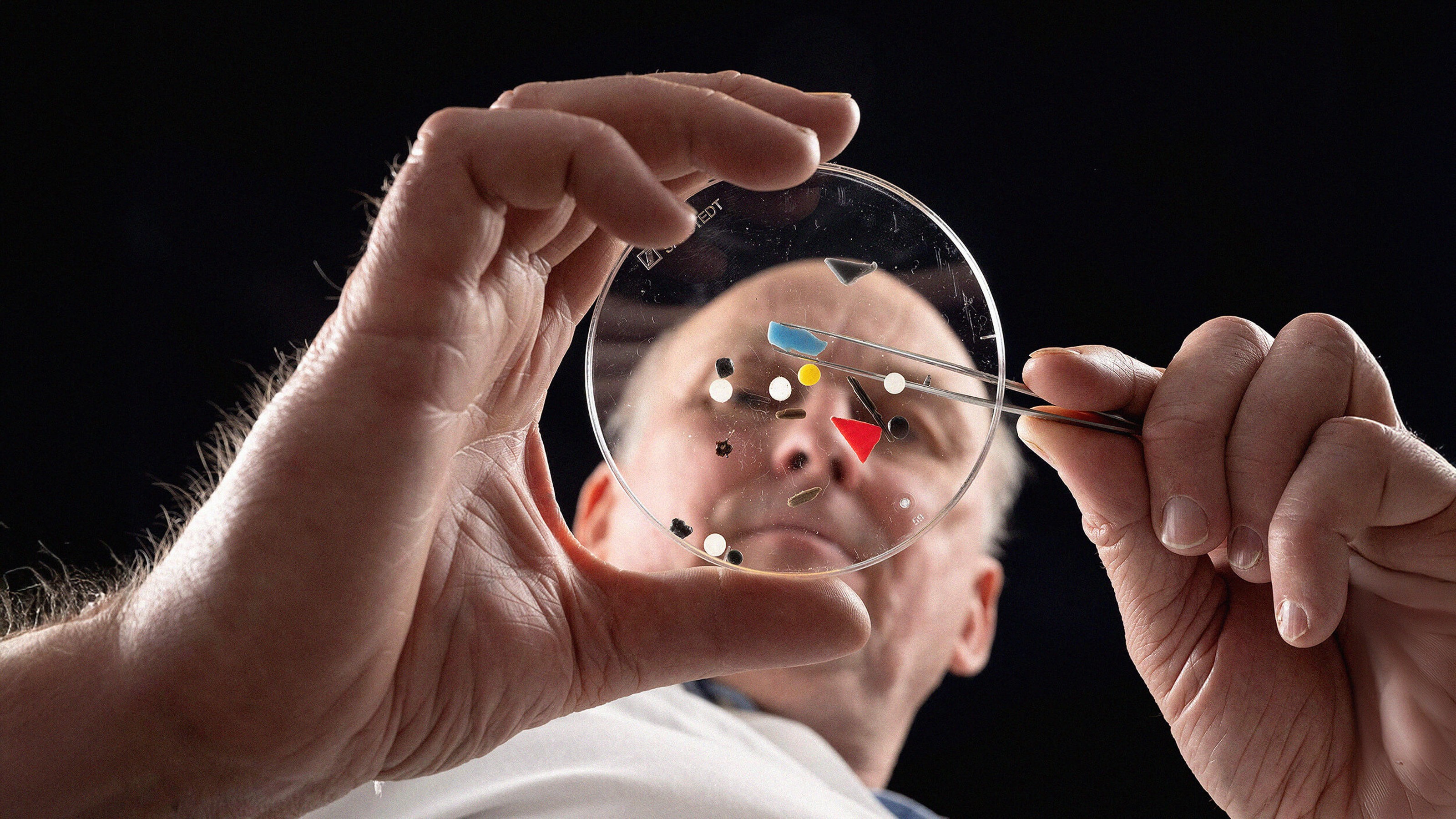

But the more I researched, the less funny it seemed. Microplastics — particles smaller than 5 millimeters— and their even tinier counterparts, nanoplastics, have infiltrated ecosystems and human bodies alike, raising new concerns about environmental and health impacts. They’re in our air, water, and food and have made it to the most remote corners of the Earth, like the deepest parts of the ocean and near the summit of Mount Everest. They’re also inside our bodies — scientists have found them in the liver, kidneys, brain, and testicles. They’ve even made their way into the placenta, which means that newborns may enter this world with a dose of microplastics. The most recent eye-catching headline? Scientists detected microplastics in dolphin breath.

I wasn’t alone in feeling panicked. A quick search on Google Trends shows an exponential rise in interest in “microplastics” since 2004, eerily following the same shape as global plastic production — a flat line that slowly gains speed, and then a sudden spike. Alongside solid science, some claims — like the alarming but refuted idea that we consume a credit card’s worth of plastic every week — are also gaining attention. The mix of credible research and sensationalized claims makes it difficult to grasp the true scale of the problem.

Before 2004, no one was Googling “microplastics” because the term didn’t exist. Dr. Richard Thompson, a Professor of Marine Biology at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, coined it after discovering tiny plastic fragments on UK beaches. His research introduced the world to a new concept: plastics small enough to infiltrate ecosystems in ways larger waste couldn’t.

U.N. summit on plastic pollution

Fast forward 20 years, Dr. Thompson is now one of the most prominent scholars involved in efforts to tackle plastic pollution, including the upcoming fifth session of the United Nations Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5). Scheduled for late November in Busan, South Korea, this meeting aims to finalize a legally binding treaty to reduce global plastic pollution.

“Since I began studying plastics, production has at least quadrupled. At the same time, we’ve also seen an encouraging shift in mindset. One hundred seventy-five countries now agree plastic pollution is a global problem that requires a concerted, international response. That’s a huge change from 20 years ago, when plastics were predominantly seen as a miracle material, not a threat.”

Despite growing awareness from the public and policymakers, plastic waste continues to flood the environment. Larger items — bottles, bags, wrappers — break down into smaller fragments over time, releasing invisible microplastics into the air, water, and soil. The process is ongoing and largely irreversible.

There’s no easy fix, but Thompson says the solution must start with a step that’s simple in principle but difficult in practice: “We need to turn off the tap.”

From miracle material to microplastic nightmare

Mass production of plastics began in earnest during the 1950s, though more than half of all the plastics ever produced have been made since 2000. Anyone who’s seen the 1967 classic The Graduate will recall the famous scene where Mr. McGuire pulls Dustin Hoffman’s character aside and offers just one word of career advice: “Plastics.” He wasn’t wrong. By the 1960s, plastics were essential to modern life — used in everything from cars to food packaging to medical applications. But waste soon became a colossal problem.

The same properties that made plastics a marvel of modern industry — durability, low cost, and versatility — also make them an environmental nightmare. Plastics don’t biodegrade. Instead, they fragment into smaller and smaller pieces, drifting across the planet through air and water currents, accumulating in ecosystems indefinitely.

Microplastics have infiltrated ecosystems worldwide — from the ocean floor to mountaintops. Marine animals, mistaking them for food, ingest these particles, leading to blockages, malnutrition, and toxic buildup. These tiny plastics have been found in more than 1300 animals, including fish, birds, and insects. Experimental studies show that exposure to microplastics can negatively affect the fertility, growth, and metabolism across a range of species. These disruptions have ripple effects across ecosystems, compromising food web stability and ecological balance.

But are microplastics really harmful to human health? Scientists have been trying to answer that, and while there are still many unknowns, the evidence so far is troubling.

Plastic production and health

The sharp rise in plastic production isn’t the only concerning trend that has emerged since the early 2000s. In fact, it mirrors an increase in health issues that don’t have clear causes. For example, sperm counts have dropped by more than 50% in some regions. Meanwhile, hormone-related cancers, early puberty in girls, and metabolic disorders like obesity have surged.

While correlation doesn’t always mean causation, research suggests that chemicals used in plastic production — specifically endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) — may be contributing to these trends. EDCs interfere with the body’s hormone systems, disrupting processes that regulate reproduction, metabolism, and brain function.

“I’ve been trying to understand why sperm counts have dropped so dramatically over the past 10 to 15 years,” says Dr. Xiaozhong (John) Yu, an environmental health researcher and professor at the College of Nursing at the University of New Mexico. “When I first saw studies that detected microplastic particles between 10 and 100 micrometers in semen samples, I wasn’t too worried. Those particles were too large to pass through biological barriers like the blood-testis barrier.”

But that changed when Yu’s colleague Dr. Matthew Campen developed an analytic technique to detect nanoplastics — particles even smaller than microplastics. Nanoplastics, ranging between 1 and 1000 nanometers, pose a serious concern because their small size allows them to enter the bloodstream and accumulate in tissue. “We tested both human and dog testicles,” Yu told me. “The results shocked me. I triple-checked our protocols. But there was no denying it — nanoplastics had breached the reproductive tissue, right where sperm production occurs.”

Although the effects of microplastic exposure remain unclear, the presence of foreign particles in reproductive tissues raises serious concerns. “The presence of a foreign body alone could interfere with delicate processes like spermatogenesis, the formation of sperm. “Also, these particles can leach chemicals and heavy metals, which may disrupt reproductive health. There’s solid theory behind these mechanisms, but studying and proving their impact on a living human is very challenging.”

The challenges of understanding microplastic toxicity

Dr. Yu and his colleagues face major challenges in understanding the full impact of microplastics on human health. One complication is the sheer diversity of plastics. There are hundreds of different types, each with its own unique set of chemicals, additives, and potential toxicity. Microplastics also vary in size and shape — from visible fragments to nanoplastics small enough to penetrate cells and tissues.

Another hurdle is that most studies so far have been conducted on animals or in laboratory settings, making it difficult to predict the effects of long-term, low-level exposure on humans. (A major problem in studying the health effects of plastics on humans centers on a lack of controls: Because plastics are everywhere, it’d be nearly impossible to compare the health outcomes of people who have been exposed to plastics and those who haven’t.)

“We simply don’t know what chronic exposure to microplastics might do to people over decades,” Yu says.

Dr. Joe Schwarcz, a chemistry instructor at McGill University and Director of the institution’s Office for Science and Society, told Big Think in January:

“The truth is that determining the possible health consequences of nanoparticle exposure is a more challenging problem than going to the Moon. Feed phthalates to rats and you can track what happens. But that doesn’t tell us anything about a risk to a child who plays on vinyl flooring that has phthalate plasticizers or chews on a PVC duck that has been plasticized.”

This uncertainty has led some to argue that it’s too soon to sound the alarm, considering we still lack enough evidence to pinpoint the exact mechanisms by which plastics may harm human health. But that kind of cautious response frustrates scientists like Dr. Yu and Dr. Thompson, who say waiting for perfect clarity is a dangerous game.

“Yes, many questions remain about how plastics affect human health and the environment — questions I’d love to know the answers to,” Thompson says. “The evidence of harm from animal models is compelling, and it would be very misguided to assume that humans are somehow immune from similar impacts. We don’t have the luxury of waiting to understand every mechanism before taking action.”

He stresses that there needs to be a shift in research priorities.

“At a recent international conference, I reviewed the abstracts, and words like ‘harm’ and ‘impact’ outnumbered ‘solutions’ or ‘intervention’ by six to one. As a research community, we need to move from simply defining the problem to developing meaningful solutions and interventions.

Turning off the tap

While new technologies can sound sexy and offer promising tools, they might not be enough to replace the need for systemic changes in how we produce, consume, and design plastic. Thompson warns against “techno-optimism.”

“One of the key benefits of plastic materials is their durability. If bacteria or biodegradable plastics were a solution to pollution in the environment, we’d also be flying in planes and driving cars that disintegrate,” he says. “Clean-up efforts and technological fixes can help, but they can also create false hope.”

Without major interventions, plastic use is expected to nearly triple by 2060, according to a 2022 OCED report. Such a rise would likely outpace our ability to manage the waste, which is one reason Thompson supports reducing production. “We can’t pull plastic out of the environment as fast as we’re putting it in. We need to cut off the input first. Once we’ve done that, we can focus on creative solutions to deal with the legacy plastic already out there.”

Professor Maria Ivanova, Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University, says, “If we stop producing plastic because we’ve developed better materials, that’s obviously part of the solution. But the real challenge is rethinking how we consume in the first place.” Ivanova, who was part of the Rwandan delegation that initially pushed the UN to begin negotiations for a global plastics treaty, will participate in the fifth summit as the head of the delegation from Northeastern University.

She recalls a conversation that stuck with her: “After a youth summit, a young woman from Morocco asked me, ‘How did my ancestors drink water if they didn’t have plastic?’ The answer, of course, was from clay pots, since clay purifies water. But we don’t have to look that far back—before the surge in plastic production in the 1970s and 80s, we managed just fine with less. We need to think about innovations that draw not only from the future but also from the past.”

The burden on consumers

While rethinking plastic design and use is crucial, expecting corporations to voluntarily reduce production and prioritize sustainability is unrealistic. That kind of altruism rarely aligns with profitability. Instead, much of the onus of responsibility has shifted — frustratingly — onto consumers.

Take my recent trip to the supermarket as an example. I bought windshield wiper fluid (housed, of course, in plastic), and at checkout, I got a fun prize: The cashier peeled off a sticker that read: “Less Plastic! Fantastic!” and stuck it on my purchase — I’m a winner, apparently because I didn’t use a plastic bag. The irony wasn’t lost on me. The sticker itself was likely made of plastic, and the gesture — while nice — hardly makes a dent in the plastic problem.

“People won’t naturally shift to consuming less or using slightly inconvenient alternatives unless they’re led into that space,” says Ivanova. “And plastic producers aren’t going to voluntarily make less money for the good of the environment and human health. We need the right kind of regulatory incentives to pull society in that direction.”

Prof. Ivanova argues that while educating consumers is important, it shouldn’t be up to individuals to choose between convenience and environmental harm.

“An individual isn’t just a consumer — they’re a citizen. And citizens should expect their governments and international agencies, like the UN, to protect their interests and make sure they don’t put poison in their bodies. Harmful and unnecessary products, like single-use plastic bags or vanity waste, shouldn’t even be part of our choices.”

She’s optimistic that the upcoming UN treaty on plastic pollution will be a significant step toward that goal. But she notes that these changes won’t come without costs, which are likely to hit poorer nations the hardest.

“Proper financing mechanisms will be crucial to ensuring a fair transition” she added.

Ivanova says that the biggest sticking point in negotiations is whether to implement production caps.

“The High-Ambition Coalition, led by Rwanda and Norway, is laser-focused on production limits,” she says. “They know that without caps, a circular economy of plastics isn’t possible.”

On the other side of the negotiations are the “Like-Minded Countries” — fossil fuel-producing nations like China, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. They argue that efforts should focus on tracking and reducing plastic waste to regulate the downstream elements of the plastic lifecycle, instead of adopting a global limit on plastic production.

So, where does the United States stand? Earlier this fall, the Biden administration voiced support for plastic production caps, aligning with the High Ambition Coalition, which includes countries like Canada, the EU, and Mexico. However, this position has sparked criticism from some U.S. politicians who argue that production caps would significantly impact the economy and increase dependency on countries with lower environmental standards for plastic production.

Congressman Dan Crenshaw of Texas has been a vocal critic, warning that such caps could harm the $543 billion U.S. plastics industry, threaten millions of American jobs, and shift reliance to foreign plastic producers who operate under much less stringent environmental regulations. In a press release, Crenshaw described the support for production caps as a “short-sighted feel-good policy,” suggesting that efforts should instead focus on improving recycling and plastic waste management.

Notably, U.S. support for production caps came before November 5th. With an upcoming Trump administration — which during its first term withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement, championed the “Drill, Baby, Drill!” slogan, rolled back methane emission regulations, eased restrictions on offshore drilling, and opened protected lands for resource extraction — American support for any form of plastic production limits is now highly uncertain.

Amid the debate among the world’s largest economies and fossil-fuel producers, Ivanova points to policies implemented by smaller countries. “Rwanda banned plastic bags nationwide in 2008, and Seychelles banned balloons in 2021,” she says. “These small countries have paved the way, and their message to larger nations is clear: ‘If we can do it, you can too.’”

With 175 countries recognizing plastic pollution as a global problem, Ivanova hopes international consensus to drive meaningful change is finally forming.

The big picture

When I told Dr. Yu about my attempt to reduce my plastic load — tossing a perfectly good plastic cutting board in the trash — he just laughed.

“I wouldn’t stress about the cutting board,” he said, brushing it off in the way only someone who spends his time studying microplastics in testicles can. “What really matters is identifying the major sources of exposure — things like the water we drink and the air we breathe. One day, I expect we’ll see EPA caps on microplastics in water and air, just like we have for heavy metals and other pollutants.”

With an air of optimism, he added: “Life with plastics is inevitable. But I think humans can solve this issue just like we’ve done with other chemicals in the past.”

It’s a reminder that we have risen to the challenge before. What you may not see as often in the endless scroll of doom-posting is the demonstrated history of success: We phased out lead in gasoline and paint, banned toxic chemicals like DDT, and pulled the ozone layer back from the brink, all through the type of concerted global action that the plastic problem needs.

It’s not to say individual choices don’t matter — but they can only take us so far. Sure, I can’t buy a single-use plastic bag in Washington, but I can still get one (for free) in Utah. And at the end of the day, microplastics don’t respect state lines or national borders — though with some luck, a future international agreement could earn more respect.

In the meantime, I’ve pulled my plastic cutting board out of the trash.