Will China’s green energy tipping point come too late?

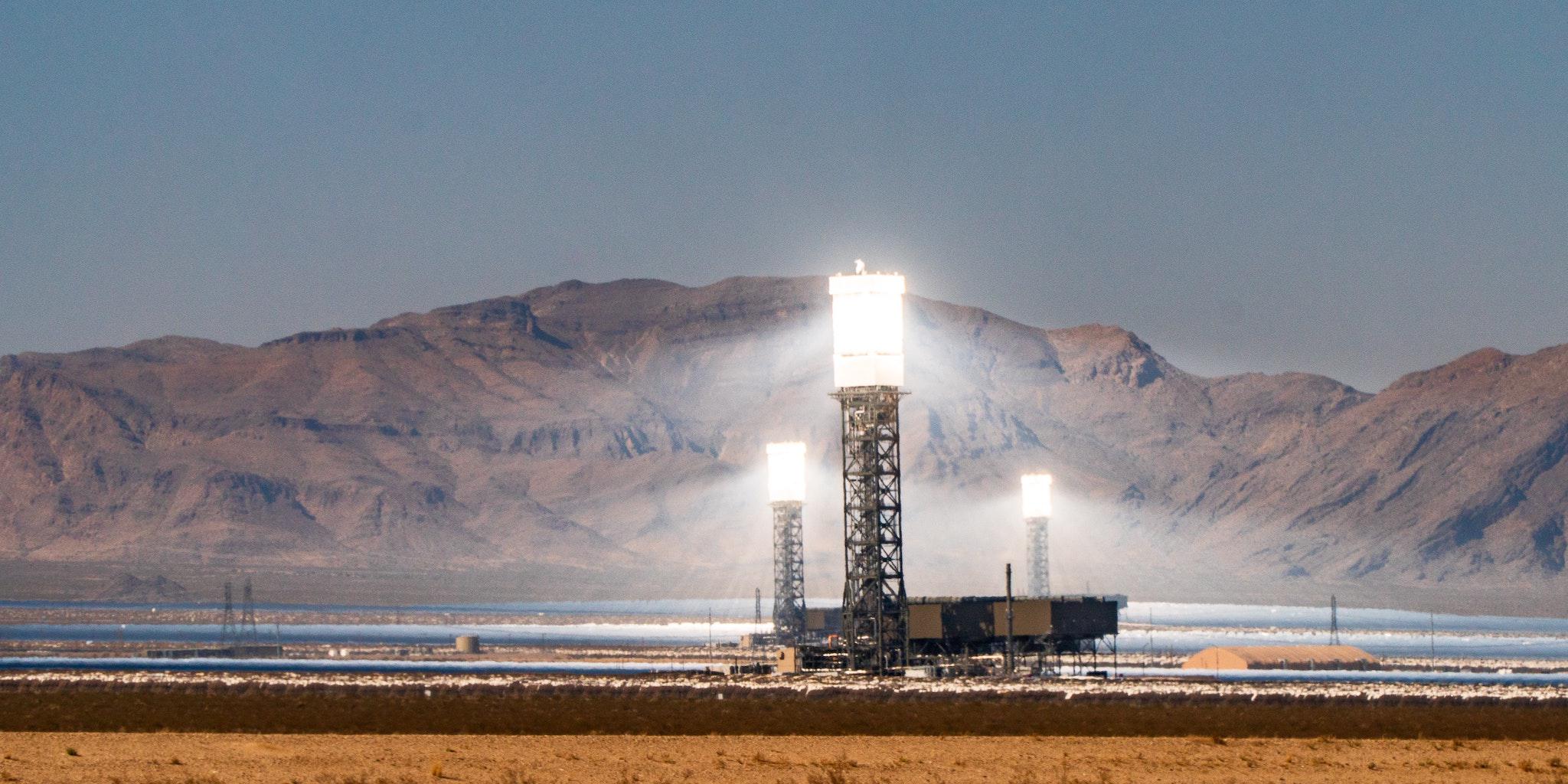

- China leads the world in numerous green energy categories.

- CO2 emissions in the country totaling more than all coal emissions in the U.S. have recently emerged.

- This seems to be an administrative-induced blip on the way towards a green energy tipping point.

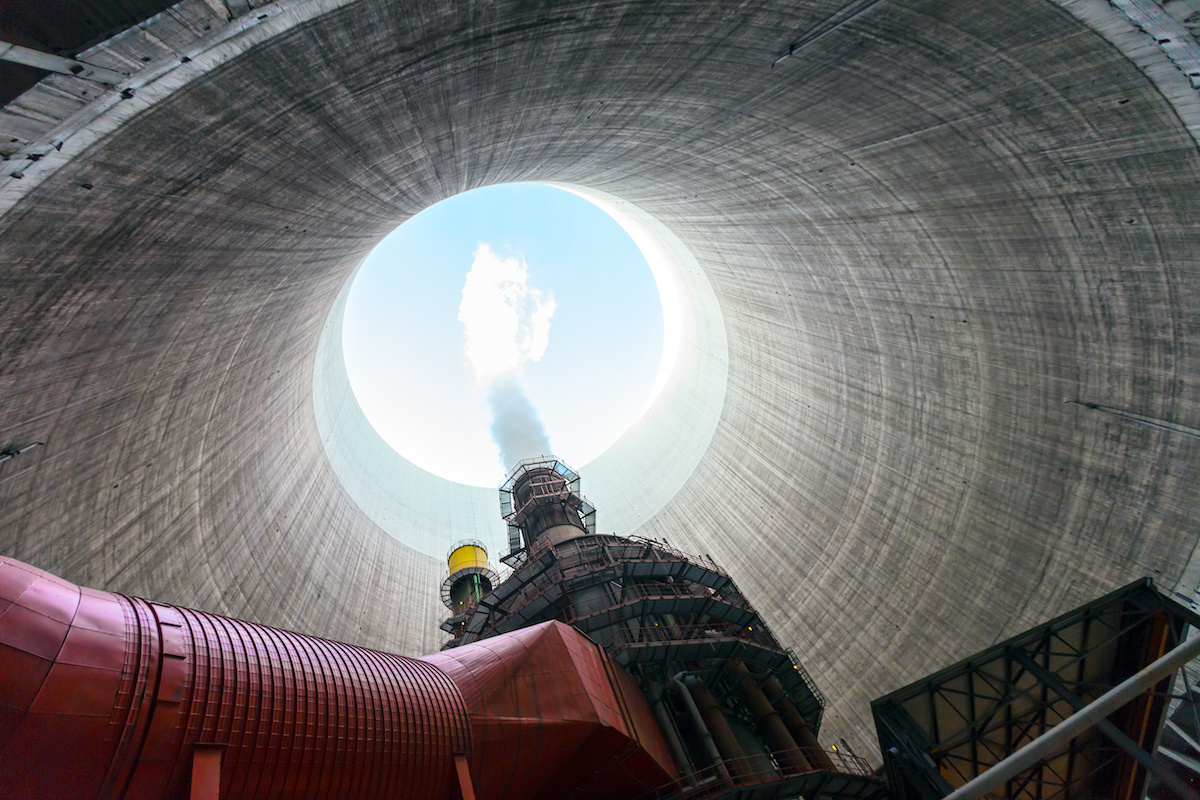

China nearly emits as much C02 per year as the U.S. and the E.U. combined. The C02 emitted by China constitutes nearly 11% of all C02 emitted in the world. As of this writing, it’s estimated that coal-fired plants will constitute 30-50% of the country’s energy consumption by 2050. This suggests a trajectory that blows well past the 12-year window as outlined by the most recent United Nations climate change report and leaves one to wonder what the ‘tipping point’ for China will be when it comes to green energy.

The wrinkle seems to have emerged from power demand outstripping supply in Shandong, Henan, Hunan, Hubei, and Zhejiang. It’s led to the equivalent of the entire coal output of the United States being built in an attempt to meet the demand. It’s also occurring in a context that saw a 7% global dip in investment in renewable energy with investment in fossil fuels picking up in 2017 (though it’s difficult to tell how much overlap there is between China firing up more coal plants and this dip occurring.)

One reason as to why this might be the case is flagged early on in a report called ‘Power Sector Reform in China‘ put forth by the International Energy Agency (IEA) this year, which notes that plant operation in China is determined “administratively.”

From the report:

Each province defines the number of full power hours that each dispatchable plant will operate during the year through the application of a fair dispatch principle that allocates the same number of hours to plants of the same type, with little consideration as to their efficiency. In addition, each province relies primarily on their own resources, limiting inter-provincial and interregional trade.

In other words, it seems to suggest that the province sets a mark to hit—a certain amount of energy to produce—based on what’s available to the province. Whether or not that aligns with overall macro trends—i.e., producing less coal—could very well be another point altogether.

From a great distance, it therefore might be possible to suss out the following: Coal is on its way to being a smaller force in China by 2040, with a decided decline beginning around 2030. Public-facing BP documents attest as much to that. The IEA estimates that coal “has already reduced its share” in China “in the power mix from 81% in 2007 to 65.5% in 2017.” But the administrative way in which bringing power online is currently set up in the country means that the country might not hit those estimates in a linear fashion.

That being said—per the IEA once again—coal will still be responsible for a majority of electricity generation by fuel across the world by 2022. And while renewable energy is estimated to continue to grow during this period and solar is growing faster than previously estimated, the question then seems to fall upon how to further incentivize divestment from coal so that China can reach a green tipping point sooner rather than later.