How KGB founder Iron Felix justified terror and mass executions

Getty Images

- Felix Dzerzhinsky led the Cheka, Soviet Union’s first secret police.

- The Cheka was infamous for executing thousands during the Red Terror of 1918.

- The Cheka later became the KGB, the spy organization where Russia’s President Putin served for years.

Attempting to change human behavior often ends up in unimaginable violence. The career and thinking of Felix Dzerzhinsky is a testament to this notion. Nicknamed Iron Felix, he founded the infamous Soviet security organization Cheka, known for its brutal enforcement of the regime. Cheka eventually became the KGB – a dangerous spy institution that gained international prominence in the Cold War. It also produced the current Russian President Vladimir Putin. He was a KGB officer for 16 years, reaching the rank of Colonel.

THE RISE OF IRON FELIX

The 20th century was the bloodiest time in human history as a result of a disastrous combination of factors. Chief among these was the horrific intersection between the mass spread of dangerous ideologies and the advancement of technologies that could harm human bodies. In the example of the Soviet Union, a project to radically transform human society resulted in millions of deaths. The 1917 Revolution attempted to institute communism by a complete re-imagining of a person’s role in their community, enacted through brute force, a novel governmental structure, and continuous re-education of large portions of the population.

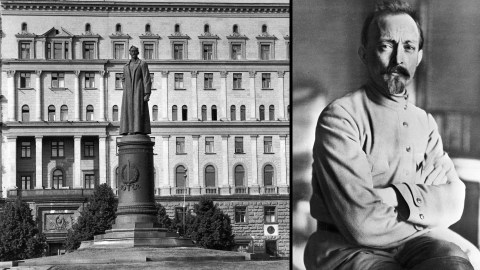

A new world needed new leaders. Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926) was one of the very instrumental figures of this effort. He was regarded as a genuine hero of the Revolution who did much to make Soviet communism possible. He was a true Bolshevik, arrested numerous times for his pre-Revolutionary activities with Polish and Lithuanian Social Democrats between 1895 and 1912. The arrests were usually followed by exiles to Siberia, from which he would subsequently escape. He did get locked up for a while between 1912 and 1917, when the February Revolution freed him.

Felix Dzerzhinsky in the Oryol prison, 1914.

THE RED TERROR

Dzerzhinsky had a key role in the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the Bolsheviks to power in Russia. A strong supporter of Vladimir Lenin, he was named in December 1917 as the head of the newly-created All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage (Cheka). This secret police had full support from Lenin in exercising all means necessary to weed out those who were perceived to be the enemies of the state. Spurred on by a failed assassination attempt on Lenin in August 1918, the fight against counter-revolutionaries became known as “the Red Terror” – a period of mass executions from September to October 1918, carried out by the Cheka with help from the Red Army.

The Cheka’s methods were very efficient. From arrest to execution would take a day. The killings happened in basements of prisons and public places. No other governmental body supervised them. While records are hard to confirm, it is believed at least 10,000 to 15,000 people were often arbitrarily killed by the Cheka during this period. The real number could possible go up to a million as some argue. The murdered were class enemies, landlords, scientists, priests or often just those who were just caught in the net. Dzerzhinsky was accepting of collateral damage, saying “The Cheka should defend the revolution and defeat the enemy, even if its sword accidentally falls on the heads of innocents.”

“We stand for organized terror – this should be frankly admitted,” said Dzerzhinsky in a chilling quote in 1918. “Terror is an absolute necessity during times of revolution. Our aim is to fight against the enemies of the Soviet Government and of the new order of life. We judge quickly. In most cases only a day passes between the apprehension of the criminal and his sentence. When confronted with evidence criminals in almost every case confess; and what argument can have greater weight than a criminal’s own confession.“

In another telling quote, he explained how he saw the purpose of the Red Terror, defining it as “the terrorization, arrests and extermination of enemies of the revolution on the basis of their class affiliation or of their pre-revolutionary roles,” as per George Leggett’s book The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police.

The inscription on the banner reads, “Death to the bourgeois and their helpers. Long live the Red Terror!

Archival photo.

THE LEGACY OF DZERZHINSKY

The Red Terror helped the Bolsheviks to hold onto power. As its leader, Dzerzhinsky developed a reputation for being a ruthless and staunch communist. He organized Russia’s first concentration camps. Besides his work with the secret police, he was tasked with reforming the economy, popularizing sports, and other key projects for the Soviet Union. He also created a system of orphanages in Russia to take in the 5 million homeless children who lost their parents during the country’s civil war and its revolution-related upheavals.

As an interesting side note, one of his other leadership roles included being the chairman of the Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema.

The Dzerzhinksy-led Cheka was transformed into the GPU (1922-1923), later becoming OGPU (1923-1934), NKVD (1934-1946) and eventually, in 1954, the KGB.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Dzerzhinksy’s legacy has undergone periods of re-examination, with his monuments toppled and the truth about what his work entailed explored. On the other hand, the Kremlin and Russia’s current leaders have tried to in some ways to rehabilitate that part of Soviet history, celebrating the founding of the Cheka, and having some monuments brought back.

A crowd watching the statue of KGB founder Dzerzhinsky being toppled on Lubyanskaya square in Moscow. August 22, 1991.

Credit: ANATOLY SAPRONENKOV/AFP/Getty Images.

Dzerzhinsky remains controversial to this day. While his work was brutal and resulted in countless deaths, those who support him see him as a hero who protected the Revolution. As the historian and a retired FSB officer Alexander Zdanovich said: “Dzerzhinsky founded a security service, one of the most powerful in the 20th century. It would be counterproductive to paint a portrait of this extraordinary man in black only.”

Of course, others like the activist Ariadna Kozina, see whitewashing figures like Dzerzhinsky as “the glorification of all the wrong parts of the past.”