Listen to (what’s likely) Frida Kahlo’s voice

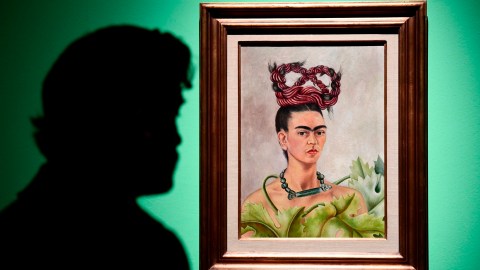

Photo credit: MIGUEL MEDINA / AFP / Getty Images

- Experts at the National Sound Library of Mexico may have discovered the first known voice recording of Frida Kahlo.

- The tape was found in the archives of a late radio personality.

- With her unforgettably surreal (and often painful) self-portraits, Kahlo challenged 20th-century notions of sexuality, class, and gender.

The National Sound Library of Mexico has discovered what could be the first known voice recording of the iconic artist Frida Kahlo.

“Frida’s voice has always been a great enigma, a never-ending search,” Pável Granados, director of the sound library, said at a press conference.

The recording was found in the archives of late radio personality Alvaro “The Bachelor” Galvez y Fuentes. On it, a female voice reads from Kahlo’s essay “Portrait of Diego” for a radio program about Mexican artist Diego Rivera, Kahlo’s husband.

“He is a gigantic, immense child, with a friendly face and a sad gaze,” the voice says. “His high, dark, extremely intelligent and big eyes rarely hold still. They almost come out of their sockets because of their swollen and protuberant eyelids — like a toad’s. They allow his gaze to take in a much wider visual field, as if they were built especially for a painter of large spaces and crowds.”

The speaker is thought to be Kahlo because she’s introduced as the female painter “who no longer exists.” (Kahlo died in 1954 at age 47.) Researchers are analyzing the tape to confirm it’s Kahlo, and they plan to search the archives in hopes of finding other potential recordings of the artist, whose voice was once described as “melodious and warm” by Gisèle Freund, a French photographer and friend of Kahlo.

“Melodious and warm” — or however you’d describe the voice in the recording — seems at odds with Kahlo’s painting style, which is often described as brooding and painful.

“I was expecting something slow and pained, dark and moody,” Waldemar Januszczak, a British art critic, toldThe New York Times. “Instead, she’s as chirpy as a schoolgirl reading her mum a poem. . . Where did all the angst go? So much younger and happier than anyone would have thought.”

“Girl with Death Mask” [Niña con máscara de calavera] by Frida Kahlo

Kahlo is still celebrated today because her work viscerally challenged 20th-century conventions of gender, class, and sexuality. As Mexico’s Culture Minister Alejandra Frausto said, she remains “one of the most iconic cultural personalities there is.”