Researchers say food prices don’t reflect environmental costs

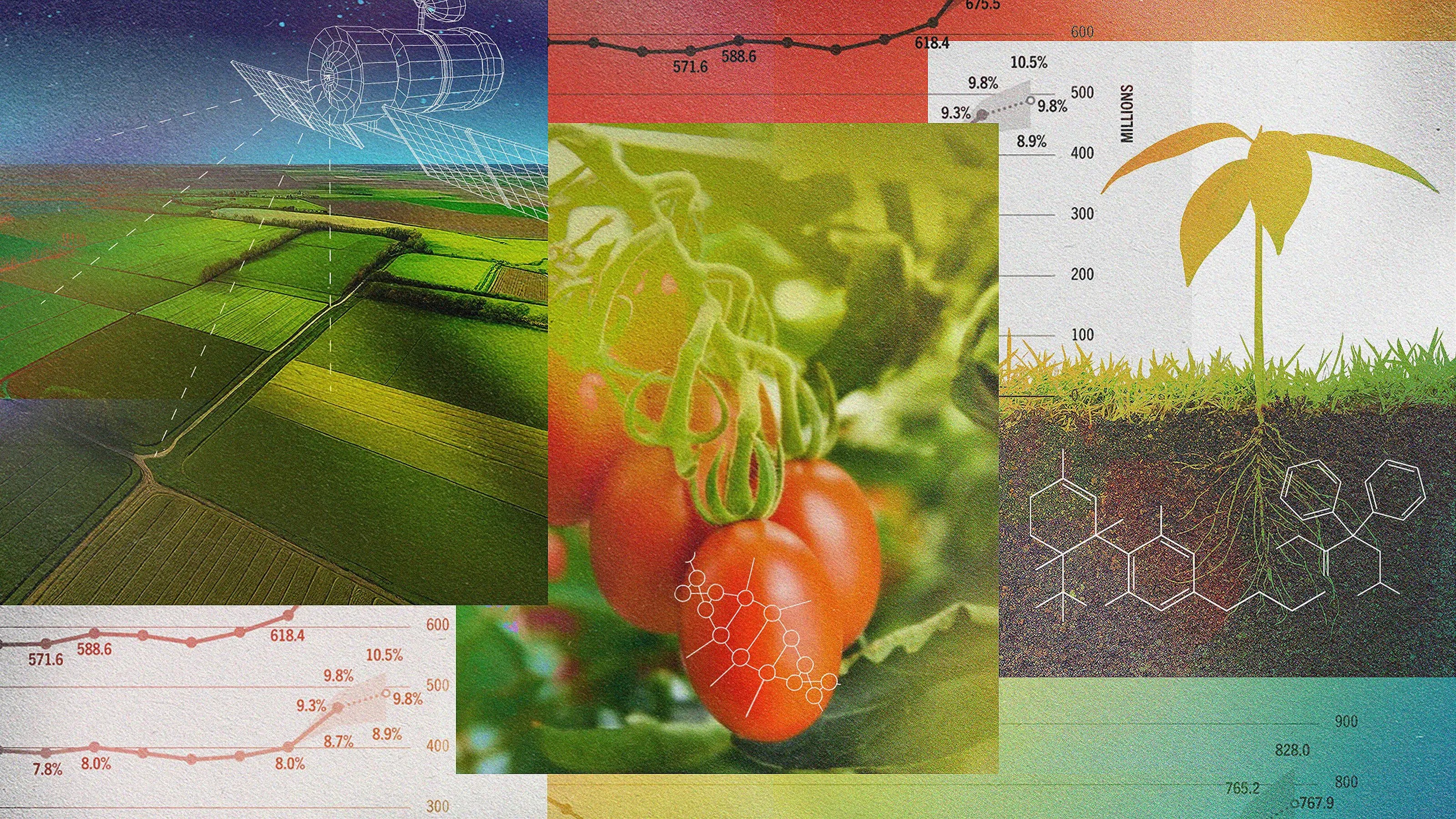

Credit: Gratisography at Pexels

- A new study shows that food products fail to include their environmental costs in their price.

- If meat products included the cost of their carbon footprints, their prices would more than double.

- Policies to factor in these costs could change food consumption in ways that lower carbon emissions.

When people think of the sources of greenhouse gas emissions, they often tend to picture urban sources. Images of coal-burning factories, giant sport utility vehicles backed up in endless traffic jams, and energy-guzzling McMansions immediately come to mind.

This conception is not entirely correct, as a significant portion of greenhouse gas emissions come from rural areas and agricultural production. Globally, a quarter of all such emissions come from agriculture. In the United States, 10 percent of all emissions have an agricultural source, roughly equal to the amount that comes from commercial and residential sources.

A new study from Augsburg University in Germany published in Nature Communications considers the carbon cost of food. Its findings could have serious ramifications for the environment, your wallet, and your diet.

Many times, the costs of a product aren’t fully reflected in the price paid for it. This is the case for the carbon footprint of many foods, as the cost of putting more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere as part of their production isn’t featured in the price at all, but is instead shifted onto the environment, society as a whole, or future generations. Suggestions that these external costs should be pushed back on the producers have been floating around for some time. In a way, this is done with various products, such as taxes on gasoline.

This study expands on previous efforts to find out what those external costs are when food is concerned.

Using life-cycle assessment (LCA) tools, the researchers determined when emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane occurred in the food production process. The effects of land use, including deforestation, related to food production were also incorporated.

The results were striking. Meat and dairy products are incredibly undervalued according to this measure. Pricing in the climate damage caused by their production would raise their prices by 146 percent and 91 percent, respectively. The prices of organic plant products would also rise, but by a mere 6 percent. Organic foods, in general, saw lower price increases than conventionally produced food products.

These findings are in agreement with (though larger) than the findings of previous studies. Study author Dr. Tobias Gaugler, an economist at Augsburg, expressed surprise at the magnitude of the results:

“We ourselves were surprised by the big difference between the food groups investigated and the resulting mispricing of animal-based food products in particular.”

If adjusted, the prices of conventionally produced meat and animal products such as eggs and milk would skyrocket. Organic products would see their costs increase as well, though this would mostly result from having to ship more food around, as organic practices lead to lower crop yields per unit area. The cost difference between organic and non-organically produced food would narrow.

Study author Amelie Michalke of the University of Greifswald argued that more honest pricing would lead to changes in consumption habits:

“If these market mispricing errors were to cease to exist or at least be reduced, this would also have a major impact on the demand for food. A food that becomes significantly more expensive will also be much less in demand.”

Particular food products are thought to be governed by the standard laws of supply and demand; if the price of one type of food rises, people will switch to another. If this is true, then a more accurate pricing of these products would presumably lead to significant changes in food consumption habits.

The authors have expressed their desire to continue investigating the environmental effects of agriculture, perhaps following this study with a dive into nitrogen emissions.