The strong economic case for hiring people with criminal records

- More than half a million people are released from America’s state and federal prisons every year.

- Research shows that stable employment reduces the chance an ex-offender will return to jail, yet it remains a rigid barrier for those trying to re-enter society.

- Hiring ex-offenders is not only humane but offers benefits for communities and businesses alike.

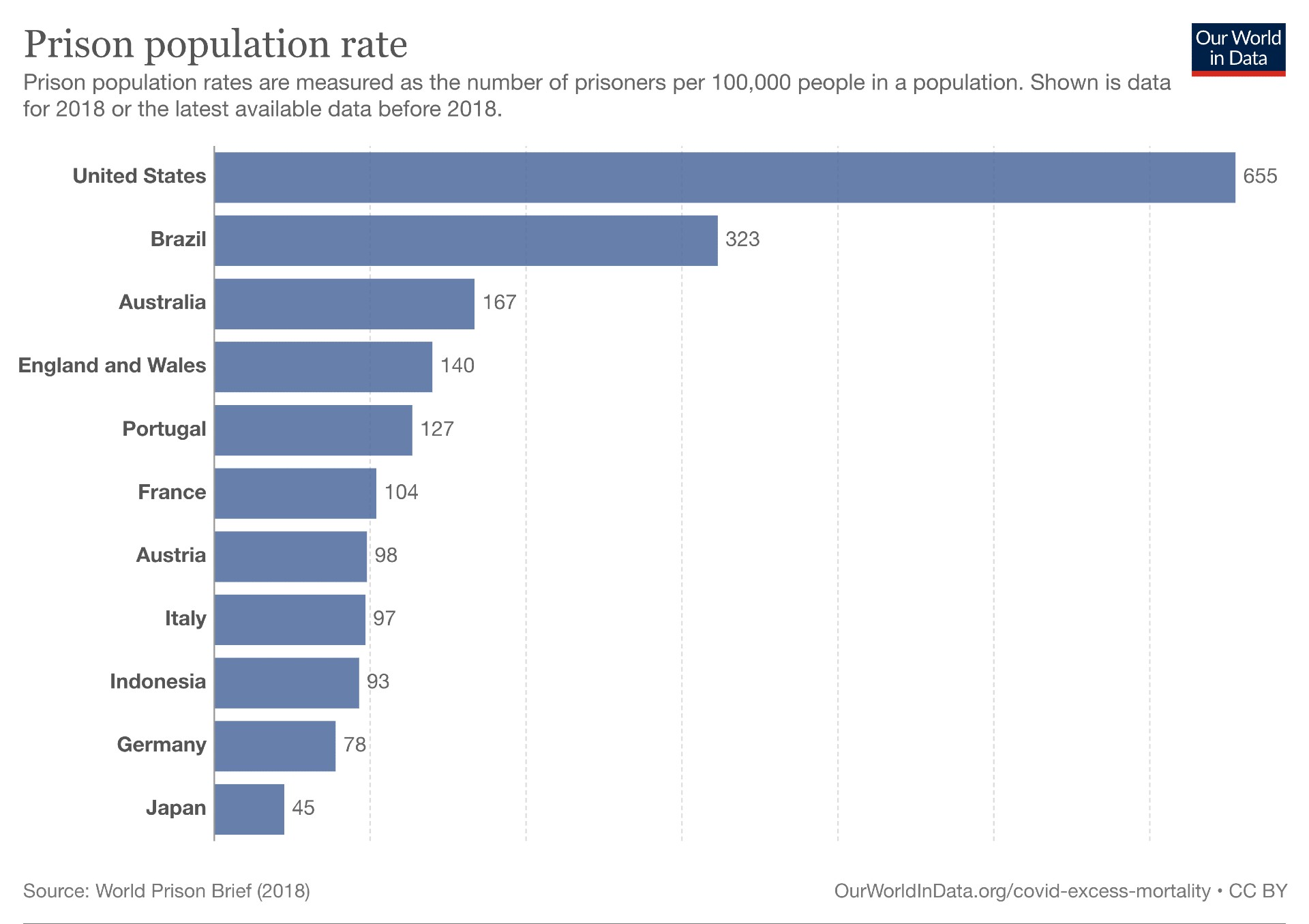

Approximately 600,000 inmates are released from America’s state and federal prisons every year. That’s an outpouring of more than 10,000 people a week who must re-enter society and re-establish lives in communities from which they may have been estranged for years. It also says nothing about the millions more cycled through the nation’s jails.

Unfortunately for most, this time doesn’t so much represent a fresh start as much as a sabbatical. By some estimates, three-quarters of those released will be arrested for new crimes within five years. If prison is meant as a form of rehabilitation, and not merely punishment, then clearly the current approach is failing these people and their communities.

For this reason, reform efforts tend to focus on improving conditions on the inside and the systemic malfeasance that sends a disproportionate number of people to prison in the first place (such as strict sentencing laws and zero-tolerance policies). And reformers are right to do so. Those facets of the criminal justice system can be rife with dysfunction and, in certain cases, depravity.

However, reform and rehabilitation must not only fix what goes on inside prisons but also the revolving door that shuffles people back in.

Between a rock and a hard place

Anyone who has ever moved to a new community knows the challenges of starting over, but ex-offenders face another level of difficulty. Many may be starting from zero, and even those receiving assistance have less than most. Immediate needs can include the very basics: clothing, food, transportation, and access to medical care. Long-term, they need employment, housing, and ongoing support.

Of those, employment is of particular concern. Numerous studies have shown that stable work reduces recidivism — that is, the tendency of an ex-offender to commit another crime — for the obvious reason that it provides the financial security they need to support themselves. Yet, employment also has become a rigid barrier that communities have erected to keep ex-offenders at the fringe.

What’s odd about this ongoing trend is that public opinion has, ostensibly, shifted from the tough-on-crime attitudes of the 1980s and 1990s. According to a survey conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), a majority of HR professionals and business leaders agree that ex-offenders work as well as others and said they desire to hire the best candidate regardless of a criminal record. Another SHRM survey found that people are generally comfortable working with nonviolent offenders or patronizing companies that hired them.

Even so, SHRM found that only 53% of HR professionals are willing to hire ex-offenders and only 10% said their organizations actively recruit from the cohort.

“I suspect that many of the respondents to surveys like this are more aware of the issue and have increased attitudes of acceptance, but if you look at hiring practices, it’s mostly talking the talk but not walking the walk,” Richard Bronson, founder and CEO of 70 Million Jobs, told SHRM. “The percentage of employers who are actually hiring from this population is much lower than 53%. Hiring one or two people in a pilot program is not fair-chance hiring.”

The reasons for such hesitation are multi-faceted and socially entrenched. One reason employers may be reluctant to hire ex-offenders is the worry that they will reoffend. Others include the fear that they will open themselves up to potential lawsuits or the belief that ex-offenders are less skilled than other candidates. Finally, there’s the matter of implicit bias.

Whatever the reason, the consequences are clear. According to a study published in Science, nearly half of all unemployed men in the U.S. were criminally convicted by the age of 35. “I’m not sure that many people understand just how prevalent an arrest is,” Sarah Esther Lageson, a sociologist at Rutgers University, who was not involved in the study, told Science. “It really shows [that unemployment] is actually a mass criminalization problem.”

Forgive and recruit

But without employment, an ex-offender descends into a vicious cycle in which he becomes likelier to reoffend. This is harming communities and businesses alike.

According to Johnny C. Taylor, president and CEO of SHRM, there are three important reasons employers should actively recruit ex-offenders: (1) It reduces recidivism and the burden on taxpayers; (2) it addresses many talent shortages in the current labor market; and (3) it offers a second chance to people who have made mistakes.

To elaborate further on the first point, communities pay taxes to send people back to prison, while ex-offenders pay taxes if they stay employed. Of course, the actual math is more complicated than that. In two reports, one released in 2012 and the other in 2017, the Vera Institute of Justice looked at state prison expenses. The institute found that sometimes prison expenditures declined as prison populations declined, sometimes they declined as populations increased, and sometimes they increased as populations declined. That’s because the bulk of state spending goes to things like salaries, pensions, and benefits for correctional officers (which can vary wildly with the local cost of living).

Thus, simple calculations of per-inmate cost can hide a prison’s effectiveness (or lack thereof). However, the institute found that the most reliable ways to reduce spending, “without jeopardizing public safety,” included reducing recidivism alongside modifying sentencing laws and release policies.

Regarding the talent shortage, ex-offenders often can help organizations address skill gaps while offering long-term benefits. For example, a study in the Journal of Labor Policy found that employees with criminal records are far less likely to quit their jobs (perhaps out of a heightened sense of loyalty). In an interview, Taylor noted SHRM research showing that ex-offenders provide the same or higher productivity rates and cost the same to hire. Some programs even offer business incentives to organizations that hire ex-offenders.

Finally, hiring ex-offenders is humanitarian. It not only advantages the ex-offender but also supports families from suffering further financial loss and stress.

“If the idea is I make a mistake at 25 years old, I go to jail for five years or prison for five years, and then I get out: what do I have to look forward to if forever I’m going to wear the scarlet letter, the convict, the C that says I’ll never get another opportunity? Life is over then. If, in fact, that’s the reality, then we have a problem,” Taylor said in an interview.

He added: “The challenge, then, is to train people and to change the narrative that all people who’ve committed crimes, who’ve been arrested, who’ve gone to prison are bad people.”

One solution among many challenges

None of this is to say that giving every ex-offender a job will solve the many challenges faced by those re-entering society as well as their communities. As noted in a report from the Brookings Institute, employment is only a moderate risk factor for recidivism. Major risk factors include antisocial personality patterns and behaviors, which are difficult to treat effectively without early diagnosis and access to mental health care.

The Brookings report also points to another important moderate risk factor: education. Ex-offenders are less likely than the general population to have a high school diploma or equivalent degree. Widening the availability of education and vocational programs alongside scholarships for incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated people will be necessary to further reduce recidivism.

“Our willingness to see the humanity in people who have been incarcerated, paid their debt to society, and reentered society starts the process of us being better and seeing the humanity in those currently within that system,” Taylor concluded.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Johnny C. Taylor Jr.’s full class for your organization, request a demo.