Baby bees hatch with damaged brains thanks to pesticides

Image source: Gill, et al/Tonio_75/Shutterstock/Big Think

- Pesticide contamination in bee hives damages the learning capabilities of offspring, according to a recently published study.

- A key area of the affected bees’ brains never correctly develops after pesticide exposure.

- Early impairment appears to be irreversible and is likely a factor in falling bee populations.

According to the U.S Department of Agriculture, some 35% of our food crops depend on bee pollination. That means about one of out every three bites of food comes to us courtesy of insects including bees, butterflies, and beetles, or from birds and bats. With the world’s pollinator populations in a snowballing state of decline, scientists are racing to discover what’s causing this and how it can be stopped. In the case of bees, pesticides — especially neonicotinoids — are the leading suspect, and studies find these chemicals infiltrating a significant percentage of bee hives. (Pesticides also show up in our own food and drink.)

Research prior focused on the damaging effects these neurotoxins have on adult bees. Now a study of young bee brains, led by Richard Gill of Imperial College in London and published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, shows that neonicotinoids do disastrous, irreversible damage to bees’ neurological development.

Image source: Mr. Meijer/Shutterstock

Broken learning

The study involved introducing neonicotinoids to the nectar consumed by members of 22 Bombus terrestris audax (buff-tailed honeybee) colonies. The learning abilities of their offspring were then measured against a control group of young bees from colonies whose food supply had not been contaminated.

The test assessed the extent to which a bee could learn to associate a specific smell with a reward, which was a sucrose solution. The bees from the neonicotinoid colony consistently fared more poorly than the control population.

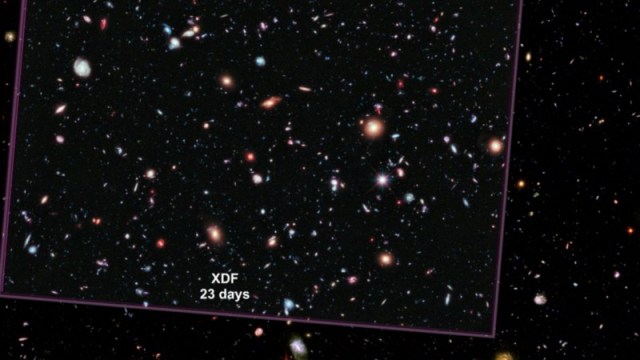

Several views of the mushroom body

Image source: Gill, et al

Tiny computed micrography (CT) scans

In hopes of identifying a structural explanation, the researchers stained the brain cells of 100 bees from the exposed colonies and took non-invasive micro-CT scans in a machine similar — albeit smaller — to those in which humans are medically imaged.

The researchers discovered a clear difference in brains of the young bees from pesticide-exposed colonies. A key brain area, the mushroom body, was found to be much smaller in these bees’ brains than it was in those from control colonies. This makes sense, since this region is believed to be involved in olfactory learning and memory.

The tests and scans were performed three days after pupal hatching and again after 12 days. The substandard learning capabilities and mushroom body sizes had not been resolved by the second test, indicating to the researchers that the damage caused by the neonicotinoids was irreversible.

(A honeybee’s life expectancy depends on its role. Drones live roughly 8 weeks, while sterile workers live for about 6 weeks in the summer or 5 months in the winter. A queen can live for a few years.)

Why this matters

The study’s conclusion does not say definitively that the mushroom area is the only brain region impacted by pesticides. However, a smaller mushroom area is significant, explaining, as it does, the mechanism by which a bee’s learning abilities and behavior may be impaired over the course of its life.

Gill says in a press release, “Worryingly in this case, when young bees are fed on pesticide-contaminated food, this caused parts of the brain to grow less, leading to older adult bees possessing smaller and functionally impaired brains; an effect that appeared to be permanent and irreversible.”

In fact, after the young bees were returned to their colonies, researchers saw lower-than-expected colony growth two to three weeks after the subjects’ reintroduction.

“If future generations of workers are predisposed to be inefficient functioning cohorts, this could lead to a density-dependent build-up of colony-level impairment increasing the risk of colony collapse.” — Gill, et al

And then there’s the adult bees

In addition to the problems caused by the behavior of bees hatched with pesticide damage, it’s not as if pesticide exposure necessarily abates later on. As lead author of the study Dylan Smith explains, “There has been growing evidence that pesticides can build up inside bee colonies. Our study reveals the risks to individuals being reared in such an environment, and that a colony’s future workforce can be affected weeks after they are first exposed.”

The study concludes that simply looking at the damaging effect of pesticide on adult bee population misses a significant, and more far-reaching, part of the story:

“Bees’ direct exposure to pesticides through residues on flowers should not be the only consideration when determining potential harm to the colony. The amount of pesticide residue present inside colonies following exposure appears to be an important measure for assessing the impact on a colony’s health in the future. ” — Gill, et al