You’ve just been declared a patron saint by the Catholic Church. What’s next?

- Much has been written about the bureaucratic process by which the Church transforms a living, breathing person into a canonized saint.

- In his new book, Trace and Aura, medievalist Patrick Boucheron explores how the significance of a saint can evolve across time.

- As illustrated by Saint Ambrose of Milan, a saint’s life is given fresh meaning by every new generation of followers.

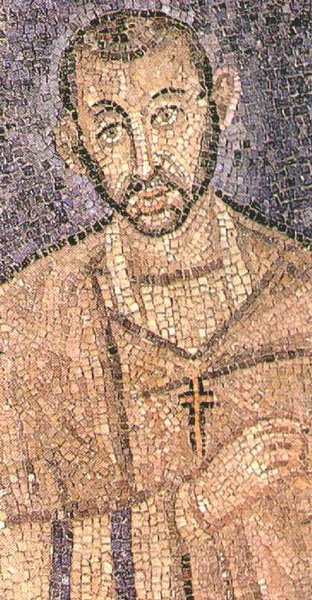

The Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio is one of the oldest churches in Milan that is still standing today. Initially named the Basilica Martyrum, it was erected in the late 4th century by Ambrose of Milan, who reigned as the city’s bishop. After Ambrose’s death, once he’d been venerated by the Catholic Church, the Basilica was dedicated entirely to his memory.

Inside this Basilica, there is a room containing papers and parchments that document the life of Saint Ambrose, as well as the other monks that lived alongside him. At first glance, the objects in this room look as though they are part of a museum exhibit. But make no mistake: To the followers of the Roman Catholic Church, not to mention the citizens of Milan, Ambrose’s personal possessions are treated as relics. They point not to the past but to the present — to Ambrose’s continuous presence in our lives.

In 2016, Al Jazeera put together an interactive article outlining the many mysterious bureaucratic steps that must be taken by the Catholic Church to turn a living, breathing person into a canonized saint. Special congregations consisting of cardinals, archbishops, and theologians — scholars that try to prove the existence of god through logic — convene at the Vatican to study the candidate’s deeds and writings, ensuring that their personal ideology was “in line with the teachings of the church.”

In order to declare someone a saint, that person must be found to possess the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance and courage, as well as the three theological ones: faith, hope, and charity. Unless a person was martyred, at which they are venerated without further investigation, they must also be found to have performed a miracle, like levitation or bilocation, which is the ability to appear in two places at the same time. Miracles performed posthumously — like when a corpse shows no sign of decaying, or emits a sweet as opposed to a pungent odor — are considered as well.

This is how saints are made on paper. In practice, it’s a little more complicated. When someone is venerated, the story of their life becomes public property, and the legacies of saints are never set in stone. Instead, they are constantly being rewritten by the conflicting and compounding interpretations of their followers. In his new book Trace and Aura, the acclaimed medievalist Patrick Boucheron explains — better perhaps than any other writer could — why the afterlife of Ambrose of Milan offers the best example of this highly abstract process.

The life and work of Saint Ambrose

Boucheron conceives of Ambrose as “one of those patched-together rememberings through which a society invents a common past, picking out the traces of what remains available.” Sanctification turns an idiosyncratic person into a streamlined concept, a kind of mirror in which people from any walk of life can recognize a part of themselves. Here, suspended in an “augmented reality,” the impressions of individual followers form a complex mosaic that both contains and builds upon that initial impression left by Ambrose the person.

The broad strokes of Ambrose’s legacy are based on his own ideas. Born to a well-to-do family near Trier, Ambrose received both secular and nonsecular education. As a bishop, Ambrose left a prodigious amount of writings, including critical analyses of the Bible, commentaries on moral and ascetical questions, and sermons. For fortifying the arguments in favor of God’s existence, Ambrose was declared one of the original Doctors of the Church: a title reserved only for the most influential of theologians.

In life, Ambrose was known as a man of principle: someone who thought long and hard about God’s world and why it works the way it does. He had many strong opinions, which he defended both in writing and through action. Among these was the opinion that liturgy — the formalities of worship, such as the sacrament of the Eucharist — should not be decided by a central authority. Instead, Christians should adapt to the traditions of the regions or communities in which they happen to find themselves.

Ambrose exerted considerable influence over the development monasticism, which at the time of his death was still in its infancy. The cloisters and nunneries that would later sprout across Europe took over many of the bishop’s principles. Like most members of the clergy, Ambrose was celibate. Unlike most members, Ambrose took his celibacy seriously. He was also an ascetic, cultivating a strong work ethic while simultaneously disavowing the material fruits of his labor; upon becoming bishop, Ambrose disowned his land and donated his wealth to charity.

Before he was a bishop, Ambrose served as governor of Aemilia-Liguria, a Roman province in northern Italy. Even after he was fully absorbed into the Church, Ambrose continued to operate like a politician. He frequently meddled in secular affairs, mediating conflict between Theodosius and Magnus Maximus. At one point, he refused to give Theodosius communion until the emperor had shown penance for war crimes committed in Greece. Befitting of a former government worker, Ambrose could sometimes demonstrate a militant hostility toward his ecclesiastical adversaries, such as when he scolded Theodosius for attempting to persecute the criminals that destroyed a synagogue.

Ambrose’s legacy rewritten

Different facets of Ambrose’s life spoke to different people. Christians concerned with the history and logic behind their faith remember him mostly for helping orthodox teachings to triumph over Arianism: an increasingly prevalent faction inside the Church that questioned and rejected the divinity of Christ. By favoring regional liturgical practices over centralized procedures, Ambrose also emphasized community while the rest of his religious organization was becoming increasingly focused on ceremony, not to mention territorial expansion.

Ambrose’s resistance against powers larger than his own — namely the Roman Empire — resonated with nationalists, separatists, progressives, and anarchists. The blows Ambrose dealt against Theodosius (and what Boucheron calls “imperial encroachments on the libertas of the Church and the Milanese commune”) transformed Ambrose into Milan’s de facto guardian angel, always rising to the occasion to protect her civil and religious liberties. After the passing of Milan’s duke Fillipo Visconti in 1447, students from the University of Pavia erected a short-lived government they named the “Golden Ambrosian Republic.”

After Ambrose’s death, it did not take long for the population of Milan to claim premium access to his legacy. Nowhere is this reflected better than in the poetic license of Ambrose’s hagiography. Feeling woefully unprepared to take on the office of bishop, Ambrose made the radical decision to leave Milan. He briefly hid inside the home of a friend, but was given up to the rest of the world when Emperor Gratian announced his enthusiastic approval of the Church’s appointment.

Many popular retellings of this incident state Ambrose was pulled back to Milan by forces beyond his control, and that there existed some kind of spiritual link between him and the city God had asked him to lead. Whether Ambrose and Milan were really connected in that way is hard to say. Today, however, it’s clear as day that the two have become as good as inseparable. “Everything in Milan,” Boucheron elucidates at the start of Trace and Aura, “is Ambrosian — or more precisely — has become so.”

From a historical perspective, Milan’s increasing fascination with Ambrose has a straightforward explanation. As the power of Rome began to dwindle and Italy splintered off into local governments that operated mostly independently of one another, Milan — like Florence — was poised to become a mighty city-state. To solidify their autonomy, the Milanese settled on their association with Saint Ambrose to construct a collective identity distinct from other city-states.

Boucheron found his title, fittingly, in a passage written by Walter Benjamin, the German-Jewish philosopher whose essays — including Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction — illuminated the way socioeconomic processes determine the way in which we interact with others. Benjamin states, in terms simpler than even Boucheron could manage, the mental machinations that ultimately turned Ambrose into a Catholic saint:

“Trace and aura. The trace is appearance of a nearness, however far removed the thing that left it behind may be. The aura is appearance of a distance, however close the thing that calls it forth. In the trace, we gain possession of the thing; in the aura it takes possession of us.”