How pirates helped turn the tide of the American Revolution

- Privateers are private vessels authorized to plunder merchant ships in times of war.

- They played an important role during the American Revolution, but were ignored by historians keen on emphasizing American patriotism.

- Despite the practice’s unsavory history, privateering during the Revolution was a noble and highly regulated enterprise.

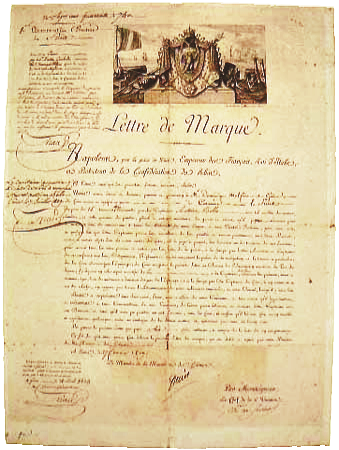

Nowadays, the term “privateer” is often used in the same breath as “buccaneer” or “pirate,” and often by people who do not know the difference between them. Technically, “privateer” refers not to a person but a ship. Specifically, courtesy of Oxford Languages, “an armed ship owned and crewed by private individuals holding a government commission and authorized for use in war.” For clarity, the individuals who operate these armed ships are called “privateersmen.”

This is but one of the many things you will learn about privateers upon reading Rebels at Sea: Privateering in the American Revolution, a book written by Eric Jay Dolin. Dolin is a former research fellow at Harvard Law School and author of books on maritime history, including Black Flags, Blue Waters: An Epic History of America’s Most Notorious Pirates, When America First Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail, and Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America.

As its subtitle suggests, Rebels at Sea is not only concerned with privateering in general, but also its significance during the American Revolutionary War. This significance, Dolin explains in the book’s introduction, was grossly overlooked by the War’s premier historians. Perhaps that’s because privateering — a non-governmental and highly lucrative enterprise — did not gel with the patriotic and self-sacrificial narrative those historians were trying to craft.

Dolin’s research reaches a different conclusion. Not only was American privateering surprisingly noble and well-regulated, but privateersmen also played an unmistakably important role in securing America’s unlikely victory against its European colonizers. While privateers rarely engaged British war ships, they plundered countless merchant vessels, depleting England’s resources and economy. Privateersmen should be remembered along the likes of John Paul Jones, not Blackbeard.

The life of a privateersman

It’s hard to know for certain why people took up privateering because privateersmen seldom wrote about their experience. We do know, based on official records, that thousands of men signed on for privateering cruises during the American Revolution. Some did so out of greed, others patriotism. Most, however, were driven by basic economic necessity as the Boston Port Act and Restraining Acts had halted maritime commerce, putting New England’s fishermen and sailors out of work.

Shipowners suffered, too. Eager to make use of their docked vessels, they asked for permission to privateer and went in search of privateersmen. These they found through word of mouth or newspaper ads. One of these ads, posted in the Boston Gazette on November 13, 1780, invites those who “love their country and want to make their fortune at one stroke” to come to the nearby wharf for a hearty welcome and a pint of grog, “which is allowed by all true seamen, to be the liquor of life.”

Grog, in case you never attended such a reception, was a mixture of water and rum, often served warm. For sailors, it was indeed the “liquor of life” as, on board, it was drunk in lieu of water, since alcohol does not spoil on long voyages. Before departing on those voyages (or cruises), privateersmen first had to sign a contract detailing payment agreements. Typically, cabin and crew were entitled to 50% of prizes taken, while the other 50% would go to the ship’s owner.

There were also bonuses: the first privateersman to spot an enemy ship would earn a 100-pound finder’s fee, while the first to board said ship would receive 300 pounds. (Note: I assume these numbers are adjusted to today’s standards, though — to my knowledge — Dolin does not mention this.) The contracts also outlined a code of conduct: Acts like mutiny, theft, or “violence to a male or indecency to a female prisoner” would result in the privateersman forfeiting their cut.

In practice, privateering was a lot like fishing, consisting of long waiting periods broken up by unpredictable, brief moments of action. Privateers traveled wherever British merchants went: to the sugar colonies in the Caribbean, around New England, and along the European and African coastlines. Spotting an enemy ship could be tricky, as many sailed under false flags. Privateersmen used trumpets to ask for identification and attacked if the enemy ship roused suspicion or attempted to flee.

Several privateers relied on brains rather than brawn. Dolin tells of the time a Philadelphia privateer called Hancock encountered a British ship that was bigger and equipped with many more cannons. A direct confrontation would end in defeat, so the Hancock changed flags and pretended to be another British ship in need of help. The enemy ship’s captain fell for the trap; as soon as he boarded the privateer, the disguise was lifted and the British were subdued.

Privateers and the American Revolution

Privateers helped the Founding Fathers in numerous ways. Most obviously, they enabled the U.S. to increase its maritime presence in short time at private expense. Increasing this presence was vital to the war effort, as Britain’s Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the entire world. In 1776, more than 270 British ships were sailing in American waters, while the Continental Navy, inexperienced and poorly organized, commanded less than 30.

Though privateers did not attack the Royal Navy directly, they still participated in the fight against King George by targeting the British economy. Every confiscated merchant vessel took money and resources away from England, causing overseas interest rates to skyrocket. The scale was immense; one privateersman, Nathanial Tracy, received 23 letters of marque, commanded 24 vessels, captured 120 British ships, and confiscated cargo with a net worth of $3,950,000.

Privateering served the American Revolution in other, subtler ways as well. The inhumane conditions captured privateersmen suffered on crowded, unsanitary, and ill-provisioned British prison ships strengthened the resolve of the Founding Fathers. “She has given us by her numberless barbarities,” Benjamin Franklin wrote of England and her prison ships in 1777, “so deep an impression of her depravity that we can never again trust her in the management of our affairs and interests.”

Dolin points out another important contribution in the form of a bill that gave the government of Massachusetts the right to authorize privateering. Massachusetts, whose maritime economy was severely damaged by the Boston Port Act, was the first American colony to give itself this power. This was no insignificant move, explains Dolin, as — according to the customs of international law — letters of marque (the legal document that authorizes privateers) could only be issued by a sovereign state.

The unsavory legacy of privateering

Despite (or perhaps because) of its importance to the Revolutionary War, the reputation of privateering remains ambiguous. “Many observers before, during, and since the Revolution,” Dolin writes in Rebels at Sea, “have argued that privateersmen were virtually indistinguishable from pirates, those enemies of all mankind who pillaged any merchant vessels they came upon, [and] tortured victims while leaving a wake of terror on the high seas purely for personal gain.”

There is, admittedly, some truth to this. Francis Drake, who received letters of marque from Queen Elizabeth during the mid-16th century, was heralded as a naval hero by Britain but known as a pirate among the South American coastal towns he raided for gold and silver. Many seamen who took up privateering turned to piracy when their employment ended. This happened after the War of Spanish Succession, which ushered in the golden age of piracy in the West Indies.

Many politicians wondered what would become of America’s privateers once the American Revolution concluded. Benjamin Franklin, once a fervent supporter of privateering, eventually referred to “the practice of robbing merchants on the high seas” as “a remnant of the ancient piracy.” He also worried its profitability could serve as an excuse for war, adding that, “though it may be accidentally beneficial to particular persons, [it] is far from being profitable to all engaged in it, or to the nation that authorizes it.”

Franklin’s view did not go uncontested. “What difference to the sufferer is it that his property is taken by a national or private armed vessel?” an editor for Baltimore’s Weekly Register wrote during the War of 1812. “One man fights for wages paid to him by the government, or a patriotic zeal for the defense of his country — another, duly authorized, and giving the proper pledges for his good conduct, undertakes to pay himself at the expense of the foe, and serve his country as effectually as the former.”

Noble pirates

If privateering had at one point in history resembled licensed piracy, this comparison did not apply to the American Revolution. “By that time,” Dolin assures, “laws had been better codified, government oversight of the practice was more effective, and legitimate privateersmen had less incentive to veer into piracy… the vast majority acted honorably, observing international law and the laws and regulations laid down by the Continental Congress during the war.”

Rebels at Sea is filled to the brim with examples of such safety regulations. Privateersmen, as mentioned, could lose their cut if they stepped out of line. Shipowners, too, were required to post a $5000 bond that would be forfeited if the privateer violated government restrictions. The colonies even set up admiralty courts to ensure prizes were registered and distributed fairly. All these measures helped ensure that privateering maintained a noble and, indeed, patriotic character.