Archaeologists find earliest known evidence of the infamous Mayan calendar

- Researchers discovered a number of fragmented hieroglyphs hidden inside a Mayan temple complex in northern Guatemala.

- One of these hieroglyphs, which depicts a deer alongside the number 7, is taken to be the earliest-known evidence for the infamous Mayan calendar.

- The calendar, a variation on the Mesoamerican calendar system, is renowned for its accuracy.

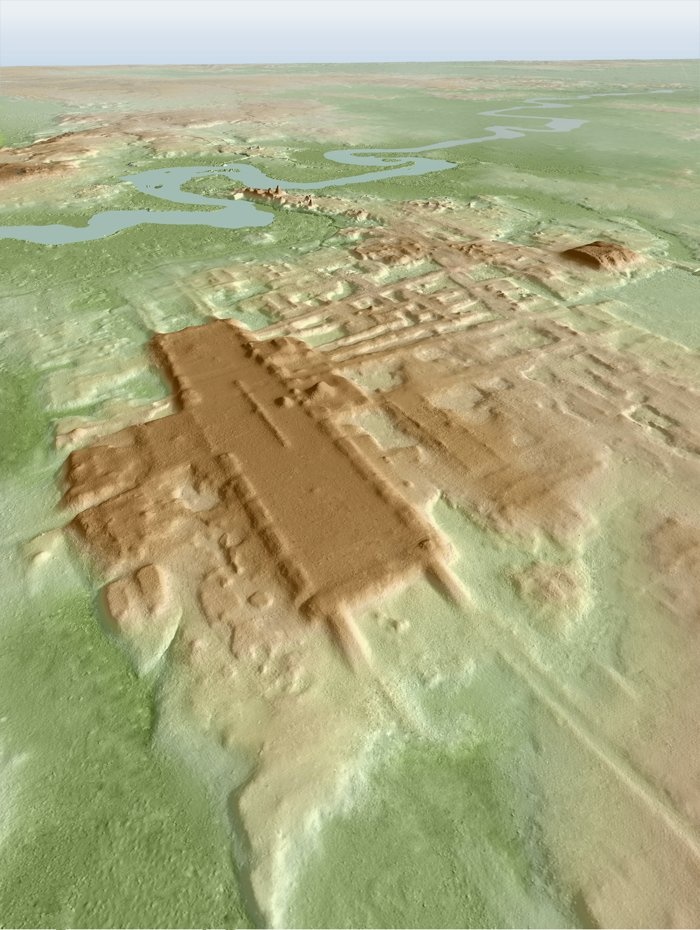

At the San Bartolo excavation site of northern Guatemala stand the remains of a Mayan architectural complex. The complex itself is made up of a pyramid, temple, and tomb. Archaeologists have named the temple “Las Pinturas” — a fitting name, considering the walls of the structure are covered with colored murals depicting scenes from Mayan mythology.

In 2001, a team of researchers carbon-dated these murals to 100 BC. However, a recent investigation of the complex discovered another set of images that turned out to be even older. These were not murals but hieroglyphic scripts. They were dated to between 300 and 200 BC, making them some of the earliest-known examples of Mesoamerican writing.

Among these hieroglyphs were a group of fragments that have been labeled “7 Deer.” The fragments were described in an article in Science Advances written by David Stuart, a professor of Mesoamerican art and writing at the University of Texas. According to Stuart, the “7 Deer” fragments represent a specific date in the Mayan calendar, making them the oldest evidence of the calendar in the region.

Mayan wall paintings

The Mayans built their architectural projects piece by piece. They started small, adding to them over time. Las Pinturas temple, for example, appears to have been constructed in seven distinct phases. Like layers of sediment, the various components of the temple give archaeologists an impression of how Mayan culture and engineering developed over time.

“San Bartolo,” Stuart and his co-authors explain, “provides excellent chronological evidence for use of artistic media in regional Late Preclassic traditions: notably, no carved stone monuments were associated with this complex and do not appear until the final architectural phase of Las Pinturas…paint on lime plaster surfaces was the dominant form of iconography and writing in lowland Maya architecture.”

Visually reconstructing the scattered ruins of San Bartolo is a little like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle. It is unclear if the hieroglyphs were part of the original complex or a structure that was added later. At any rate, the fragments were not painted in a uniform style; some were densely painted, while others were drawn with delicate lines while leaving large margins of unpainted plaster.

Although the glyphs were produced earlier than the murals, they are just as sophisticated in their design and application. They feature imagery from Mayan religious reliefs, like the maize god, along with text. The images were made using a variety of highly processed iron mineral pigments, with colors ranging from dark red to light red to pink and yellow.

The Mayans also used two different types of black pigment, one iron-based and one carbon-based. X-ray fluorescence spectra previously revealed iron-based pigment was used for calligraphic lines, while carbon-based pigment might have been used for hieroglyphic texts. This indicates that Mayan wall painting was highly methodical and “consistent with a well-established tradition of master artists.”

The Mayan calendar and “7 Deer”

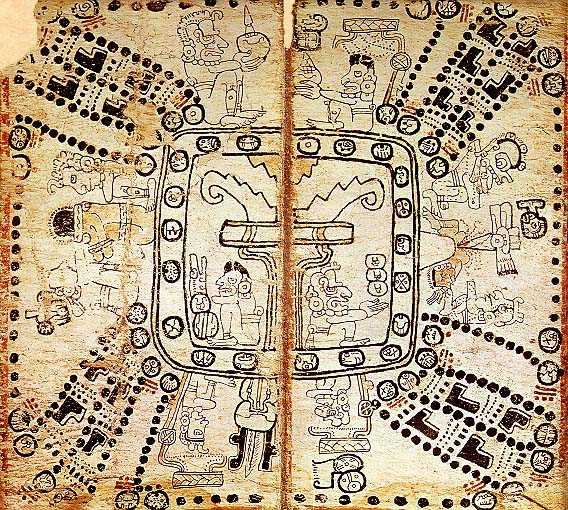

One glyph in particular caught the attention of the archaeologists, and not just because it was larger than the others. It shows the head of what appears to be a deer, above which are a bar and a dot: two symbols that together represent the number 7. Its form, Stuart’s article declares, suggests this glyph represents a specific date record in the Mesoamerican 260-day calendar.

“The 260-day count,” the article continues, “is the traditional divination calendar used throughout ancient Mesoamerica, surviving up to the present among some indigenous communities in southern Mexico and Guatemala.” The Mesoamerican calendar system, of which the Mayan calendar is the most well-known iteration, is the most intricate and accurate ancient calendar ever created.

The Mesoamerican calendar system, as its name suggests, was not unique to the Mayans. Basic variations of the same system were used by every major pre-Columbian civilization. In all cases, specific dates are represented by two elements: a number and a name. The numbers range from one to 13, which are combined with one of twenty names. Examples include “7 Deer,” “8 Rabbit,” “9 Water,” and “10 Dog.”

According to Stuart, the meanings of the names “were often similar across languages, forging a calendar system that came to be an elemental factor in the definition of ‘Mesoamerica’ as a cultural region.” For example, Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and some Mayan languages all use their respective words for “deer” to represent the seventh day.

The iconography of the “7 Deer” glyph betrays its age. As the article explains, deer were used to represent the seventh day during the Preclassic period, which lasted until about 200 AD. Starting shortly before the Early Classic period (200 to 500 AD), Mayan calendars replaced the image with that of a hand sign (in this case, depicting a thumb and forefinger touching). This change may have taken place due to the fact that, phonetically, the Mayan words for deer (chij) and the aforementioned hand sign (chi) were very similar.

Radiocarbon tests dated the hieroglyphs between 300 and 200 BC, leading Stuart and co-authors to believe the glyph (of the deer’s head) “may represent an early stage in Maya script development before the purely phonetic chi hand emerged as the standard.”

Convoluted chronology

The discovery of the “7 Deer” glyph muddies our understanding of how the Mayan calendar evolved. Previously, it was assumed the system evolved in the Late Preclassic period near Oaxaca. However, the artistic maturity and technological sophistication of the San Bartolo fragments suggests the system is much older, possibly originating during the Middle Preclassic or even earlier.

“The 260-day calendar,” the article concludes, “has long been a key element in the traditional definitions of Mesoamerica as a cultural region, and its persistence in many communities up to the present day stands as a testament of its importance in religious and social life. Our ability to trace its early use back some 23 centuries stands as another testament to its historical and cultural significance.”