How humanity discovered we’re all made of “star stuff”

- In 1973, Sagan memorably declared that we “are made of star stuff,” meaning the elements in our bodies were forged in ancient stars and then dispersed across the cosmos.

- The idea that our bodies share a cosmic lineage with stars has roots in ancient debates, and scientific breakthroughs in the 19th century enabled scientists to begin claiming with confidence that we are made of the same materials as stars.

- In this essay, Thomas Moynihan traces the intellectual history of this seismic shift in worldview.

Each one of us — in a very physical and physiological way — is 13.8 billion years old. This is the age of the Universe. It took our cosmos this long to forge the elements and build up the cumulative complexity that makes us what we are. It took the Universe 13.8 billion years to create creatures capable of realizing they are the result of an agglomeration this lengthy.

This is another way of understanding one of Carl Sagan’s most famous sayings. In 1973, Sagan memorably declared we “are made of star stuff.” By this, he meant that the matter within our bodies is the byproduct of deceased stars. We, quite literally, are ancient stardust.

But people haven’t always appreciated this. Far from it. What’s more, Sagan was far from the first to claim we are forged of “star stuff.” The debate — about whether our bodies are comprised of the same ingredients as suns — has raged for centuries. This is the story of how we figured out we are descended from the chemical cauldrons that are suns, and how this transformed our sense of who and what we are.

A seismic shift in worldview

As far back as the early 1500s, the pioneering Swiss alchemist Paracelsus was confidently stating our bodies “are not derived from the heavenly bodies.” The stars “have nothing to do” with us, he stressed: their material bequeaths no “property” nor “essence” to us. Going even further, Paracelsus declared that, even if there “had never been” any stars, humans would have been born — and would continue being born — without noticing any significant difference. He acknowledged we, of course, need our Sun, for warmth and light. But “beyond that,” the distant stars “are neither part of us nor we of them.”

Paracelsus was not alone in this. The dominant view, tracing back to Aristotle, had long assumed that the Earth and other celestial bodies weren’t just separated by a chasm in space, but by distinctions in all other qualities too. The terrestrial and heavenly realms were thought of as separate spheres of existence — governed by entirely different laws and constituted from different materials.

But in the decades after Paracelsus passed away in 1541, a revolution began, merging these two domains by proving the heavenly and Earthly were governed by the same rules. This was thanks to Galileo, his telescope, and the founding of the modern scientific method. As Francis Bacon summed up in 1612, the “separation supposed betwixt” the celestial and the terrestrial had been proved “a fiction.” The forces shaping things down here, Bacon stressed, are the same as those driving orbits up there.

This was a seismic shift in worldview, the proportions of which are hard for us to appreciate today. Throughout the 1600s, ponderers like René Descartes began announcing it means we can conclude the “matter of the heavens and of the earth is one and the same.” But even though the following century saw the building of ever-bigger telescopes — to better spy on distant stars — there still remained no way of conclusively confirming this fact. For all anyone knew, the heavens could be made of elements completely alien to those found on Earth.

As the 1800s opened, the stars still seemed distant and unfamiliar enough that the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel could dispassionately compare them to a “rash” besmirching the night sky.

Similarly dismissive, the influential French polymath Auguste Comte asserted in 1835 that our species would never ascertain the elemental ingredients of suns. He boasted that not even the “remotest” posterity will unlock knowledge about the bodily properties of objects beyond our Solar System.

“We must keep carefully apart the idea of the Solar System and that of the Universe,” Comte continued curmudgeonly, “and be always assured that our only true interest is in the former.” For Comte, this proved no tragedy or privation. “If knowledge of the starry heavens is forbidden,” he explained, “it is no real consequence to us.”

Inventor of words like “sociology” and “altruism,” otherwise impressively prescient, Comte was being overconfident. It’s no understatement to say this was — and remains — one of the worst-ever predictions about the future of human inquiry.

In 1859, just two years after Comte died, the field of spectroscopy was founded by Gustav Robert Kirchoff and Robert Bunsen. Using analysis of light emitted and absorbed by objects to ascertain their chemical constitution, their method eventually proved the stars are made of the same elements we find laced throughout mundane matter on Earth. This was thanks to work conducted by Margaret and William Huggins from their private observatory in South London. They proved Paracelsus wrong, and Comte along with him.

In ensuing decades, scientists began announcing that “the whole visible Universe” — from our “central star” to the outermost “nebulae” — had been “reached by our chemistry, seized by our analysis, and made to furnish the proof that all matter is one.” Ninety-one years before Sagan said the same thing, in August 1882, the French spectroscopist Jules Janssen made the claim: “these stars are made of the same stuff as we.”

People found comfort in this. During a 1918 speech, the Canadian poet and physician Albert D. Watson declared that, thanks to the spectroscope, “loftier qualities of our being” were being revealed — hitherto invisible to us. “We are made of universal and divine ingredients,” Watson explained.

He saw this as salutary: It means we should start acting accordingly, to live up to the station implied by our “ingredients.” If we are made of “universal” elements, so too should our “conduct, ambitions, and aspirations” assume an identical scope. Ashes to ashes and dust to dust may still apply, but at least each passing life is a corpuscle made from the same ash as stars.

Others felt similarly. In 1923, the Harvard astronomer Harlow Shapley mused that “man, beast, rock, and star” are all part of the same corporeal family. Astronomy’s “recent” breakthroughs, he explained, have confirmed “the uniformity of all chemical composition.”

“We would ask for no higher immortality,” Shapley concluded, than to be “made of the same undying stuff as the rest of creation.”

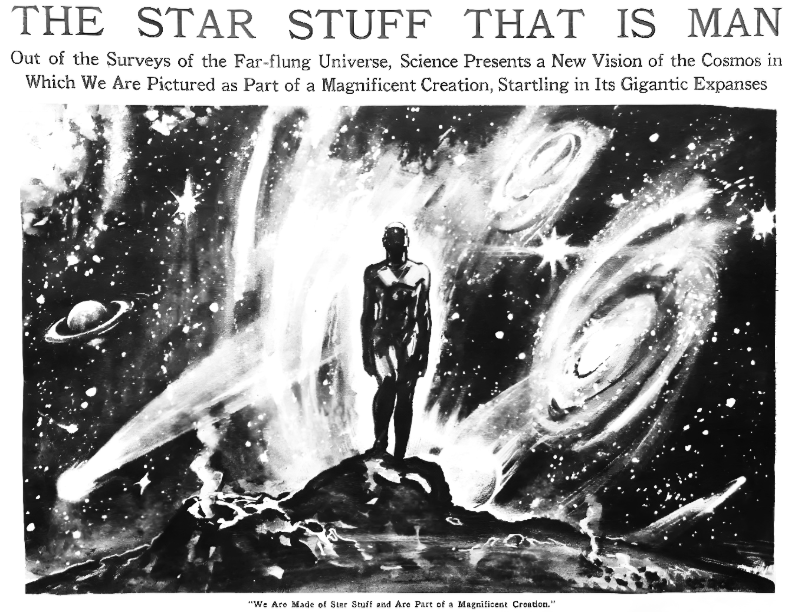

Shapley reiterated the same message, six years later, in an interview making the cover of The New York Times. It was accompanied by a striking illustration, depicting a human figure against a backdrop of spiral galaxies and streaking comets. The title read: “The Star Stuff That Is Man.” In terms of bodily makeup, we seemed siblings to the stars.

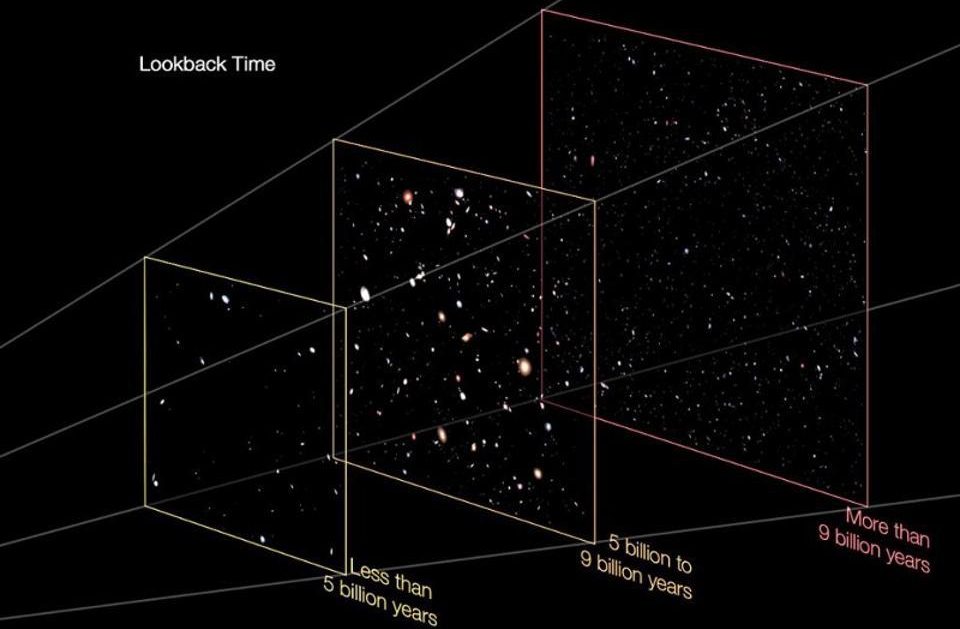

It’s telling Shapley used words like “undying” and “immortality.” It was, at this time, still an open question as to whether the Universe itself was eternal. The evidence had not yet been gathered to decide conclusively either way. Assuming the cosmos was eternal, as most scientists back then did, it was also possible to hold that life itself had also never begun: that living things simply have always existed and forever will, circulating like dust motes in an undying cosmic swirl.

But then, as the century wore on, evidence began accumulating indicating the Universe itself — and therefore, also, matter as a whole — had a hot beginning. Scientists also began remarking that, if this is true, there must have been a time when life also — cosmically speaking — could not have existed, anywhere.

Through the 1940s, the Russian polymath George Gamow developed theories explaining how the most abundant and lightest elements — hydrogen and helium — had been forged in the Universe’s fiery, explosive beginning. But our bodies are comprised of heavier, more complicated elements than these: carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, sulphur.

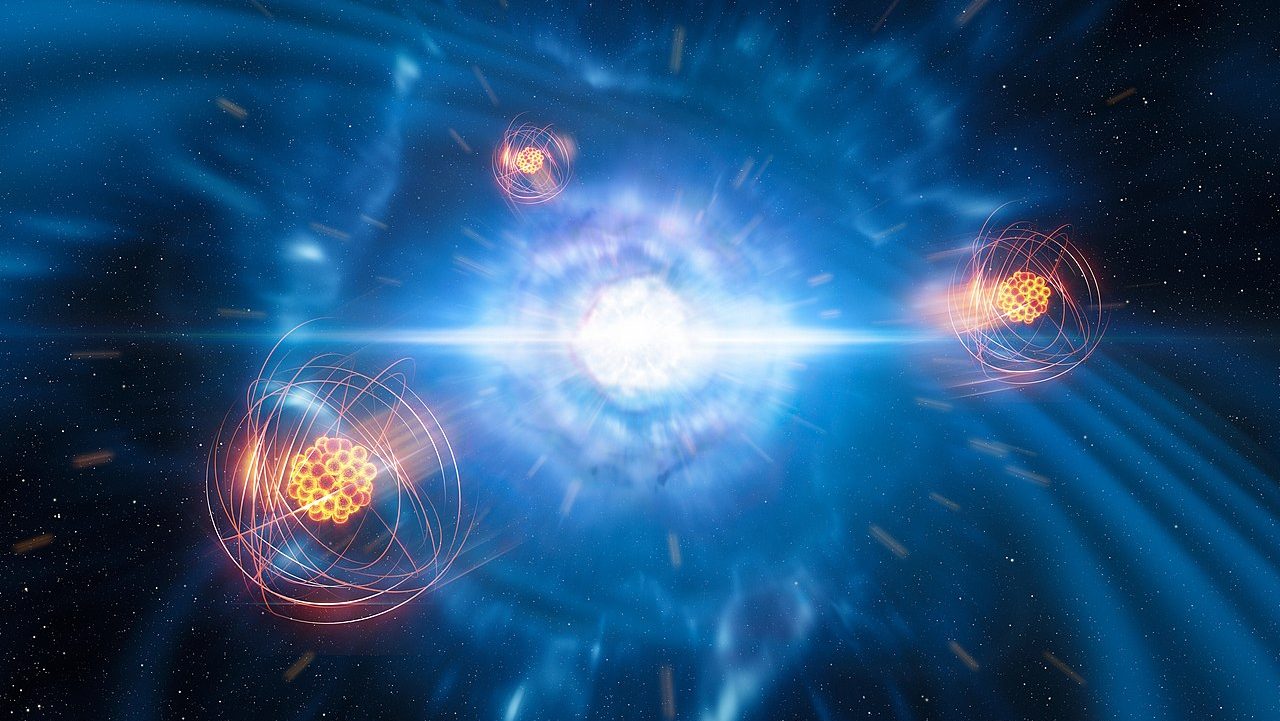

It fell to the intransigent English astronomer Fred Hoyle to expose — through the 1940s and 1950s — how the heavier elements of our living world had all been cooked within dying stars: by fusing simpler nuclei into more complicated arrangements, before puffing them out into space via the solar death rattle that is a supernova explosion.

In this way, the evolutionary ancestry of all matter had been revealed. Hoyle unveiled the processes through which heavier elements are built up from the lightest, by the systole and diastole of dying stars. He also, through this, revealed our umbilical link to some of the most powerful energetic events in the cosmos.

The children of stars

We aren’t siblings of stars, it turned out. Given we are made from elements originally forged within senile suns, it is truer to say we are their children. This is our genetic link to the Universe: our shared cosmic heritage, the ancient atomic alchemy of the cosmos.

Adding a Shakespearean spin to the motif, the journalist George W. Gray — whilst reflecting on Hoyle’s revelations — mused that “we are such stuff as stars are made of.” “The sense of kinship of life stuff with star stuff is inescapable,” Gray continued, and it touches “physicists” as much as “sentimental laymen.”

From here, the motif became common parlance for popular science. Just a few years prior to Sagan, the German writer Hoimar von Ditfurth repeated the phrase in his 1970 book Children of the Universe. The cosmos, Ditfurth reflected, “used an entire Milky Way, with its hundreds of billions of suns in order to create the commonplace objects that surround us.”

Continuing, Ditfurth marveled: “if certain vast cosmic events had not taken place, nothing in our everyday world would now exist.” This is why, in a very literal sense, each one of us is roughly 13.8 billion years old.

Each of us isn’t just a product of events in our early childhoods, which continue shaping the way we are today. The same link — of the present to the past — applies just as much to events, interlinked, leading all the way back to the Big Bang. Had they not happened, or happened differently, we wouldn’t be here to ponder today.

Across the ages, one of the eldest assumptions has been that the basic building blocks of our world are sealed away from time. That is, that while the things built from matter, from mountains to monkeys, have ancestries and biographies — in the sense they are born, develop, and decay — atoms themselves don’t suffer such inconveniences. The elements were assumed eternal: not subject to change.

One of the deepest, most surprising, revelations of modern science — uncovered thanks to our probing into things at the largest and smallest scales — has been that matter itself has its biography. That is, the elements have a family history, where what’s simpler sometimes becomes the parent of things more complex. The truth of common descent stretches far beyond biology. When Sagan pronounced that “we are made of star stuff,” he was contributing his bit to this centuries-long effort: representing our cumulative, collective fight to figure out our place in this cosmos and our relationship to it. It turns out this relationship is parental, in the most profound sense. Our very atoms betray the birthmarks of our amniotic link to this aging, explosive Universe.