How the search for dinosaurs on Venus exposed a warning for Earth

- A century ago, many people believed that dinosaurs roamed Venus.

- It was commonly thought that other planets in our Solar System had developmental stories similar to Earth.

- In 1962, NASA’s Mariner 2 flew by Venus and confirmed the planet was inhabitable, a finding that led people to think differently about Earth’s climate future.

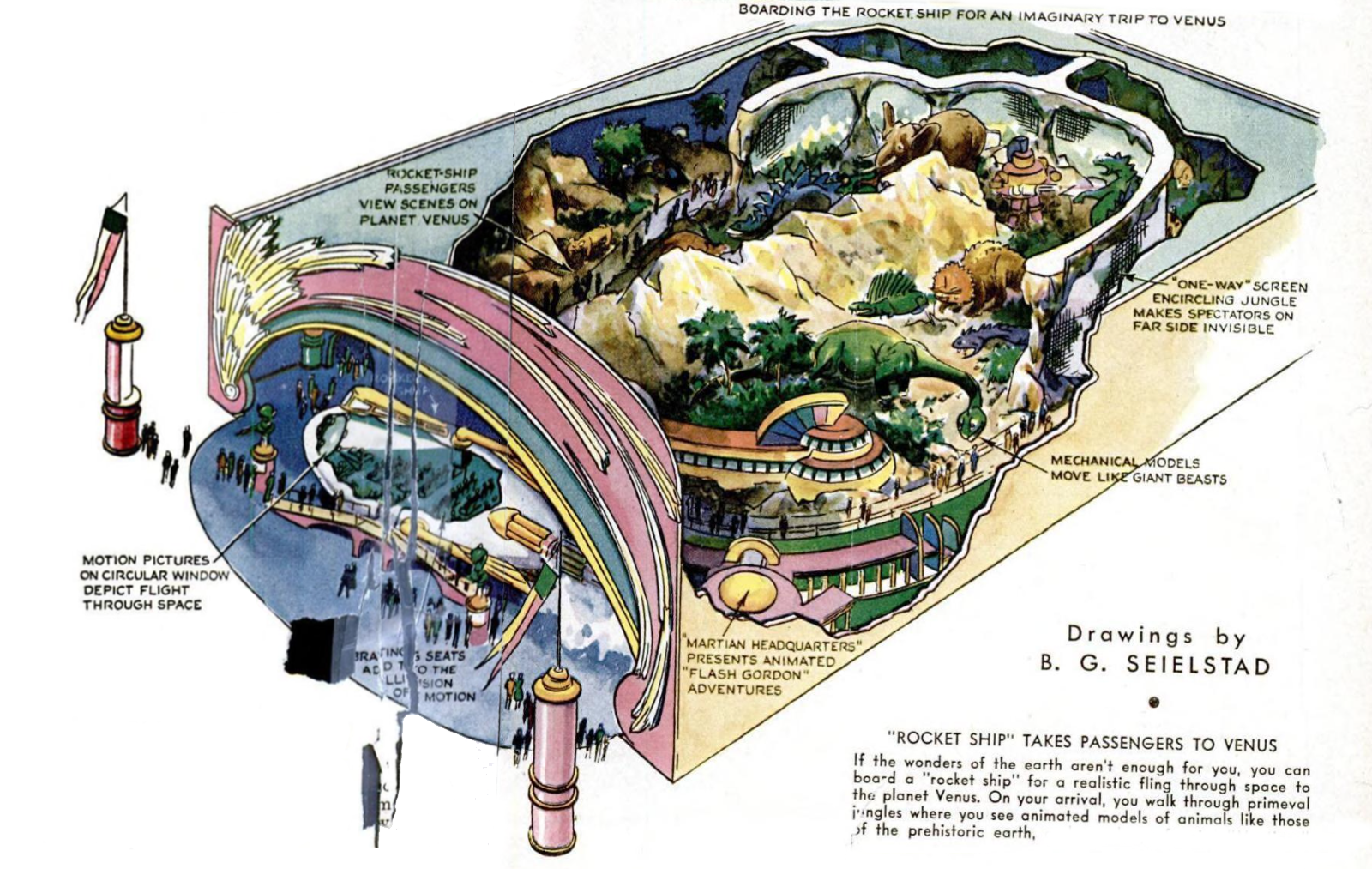

For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, a ride was advertised for the Amusement Zone whisking visitors on a “rocket trip” to Venus. Upon arriving on our neighboring planet, ridegoers were to be greeted by animatronic dinosaurs. A company with experience building such marvels had been commissioned to make them, having recently secured the first patent for the mechanics behind reanimating prehistoric beasts.

Unfortunately, the interplanetary ride wasn’t finished. The dinosaurs never got made. However, had attendees at the World’s Fair come face-to-face with them during their trip to Venus, the encounter wouldn’t have surprised them one bit.

This is because, a century ago, it was common — for both non-experts and scientists alike — to assume Venus was populated with dinosaurs. As one newspaper reported in 1946, “…if you want a date with [a] Diplodocus, Venus is your destination.”

The following is the unlikely story of how this belief — in Venusian brontosaurs — was toppled, and how this helped lead to awareness of climate change here on Earth.

“Blank slate” worlds

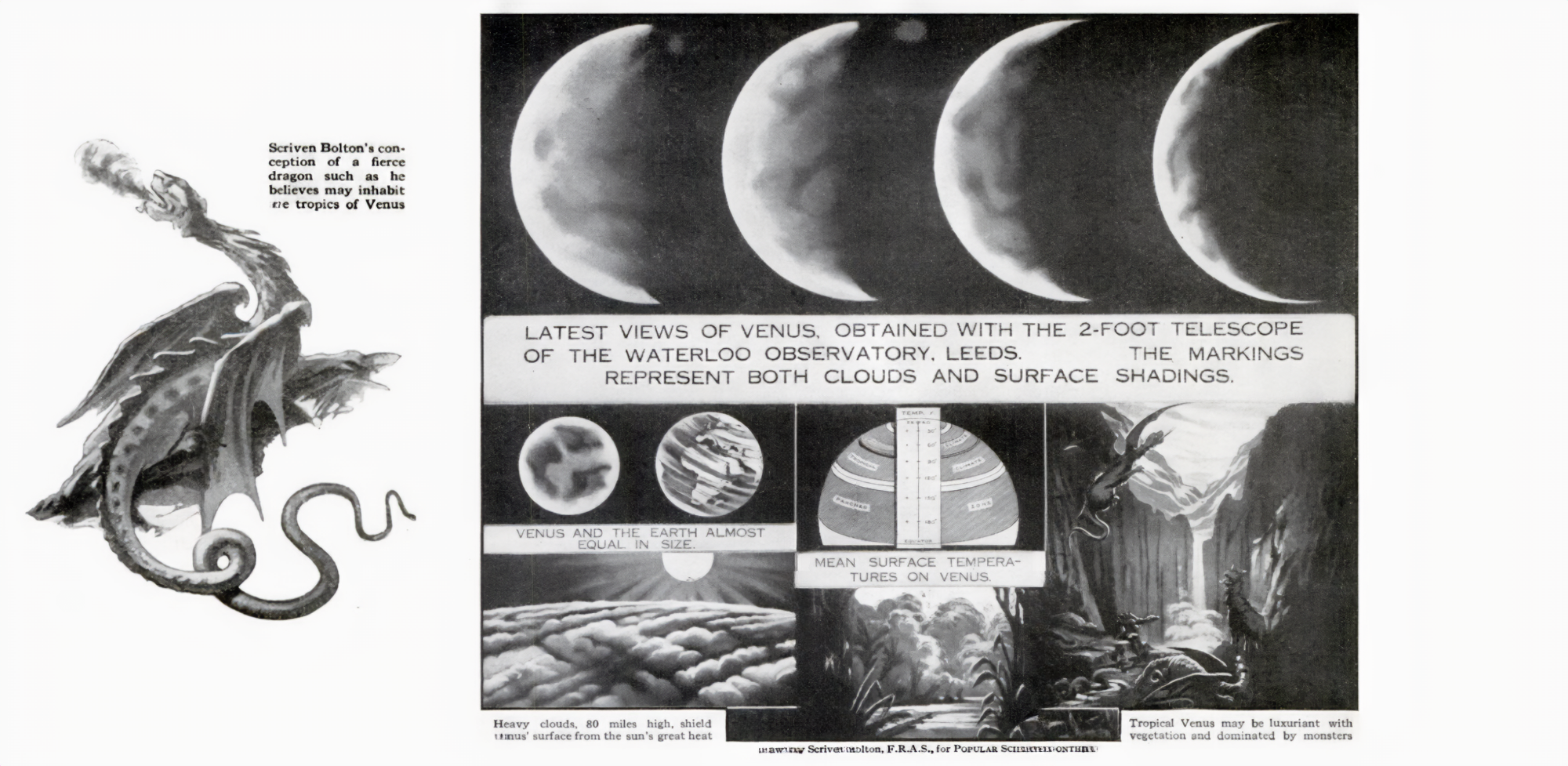

For centuries, astronomers suspected Venus shines so bright in night skies because thick, reflective clouds encompass it. This was confirmed when, during a transit in front of the Sun, our neighbor’s silhouette was observed to be fuzzy, like a mirage, not crisp or clear-cut.

Venus has a thick, swirling atmosphere. Aside from its identical size, this is why it is often called Earth’s twin. Highly reflective, making it dazzle even in dawn skies, these globe-girdling clouds completely obscure the Venusian surface. They prove impenetrable to traditional telescopes.

Unlike Mars, whose atmosphere is paper-thin, Venus’s shrouds enabled it to become a “blank slate” onto which wishful fantasies could be projected. The planet accordingly became a well-worn destination for dreamers and speculators, where many couldn’t help but imagine its veiled surface teeming with life.

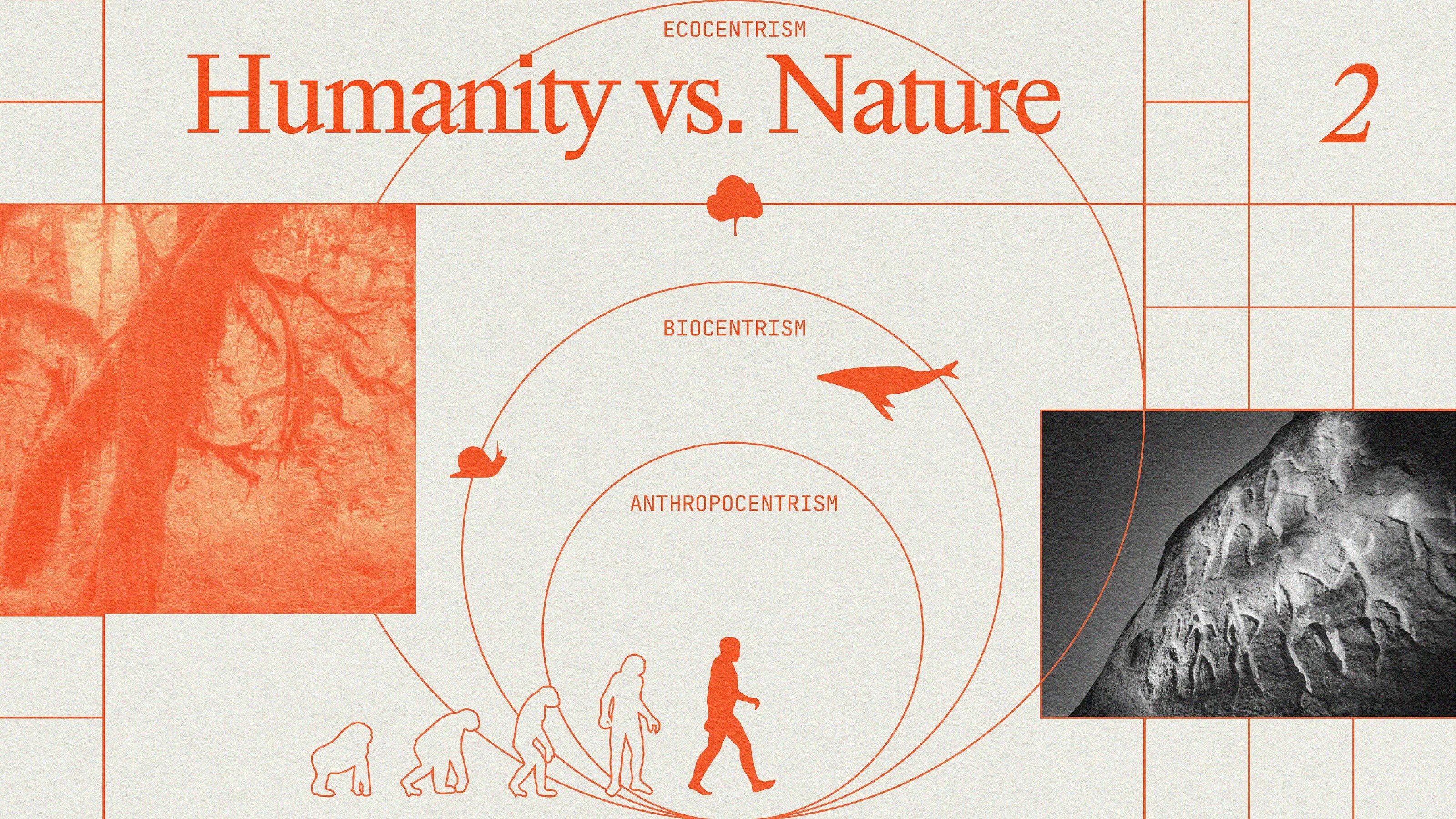

Venus served as Earth’s mirror image, often assumed to have mirrored species. Indeed, by the close of the 1800s, everyone accepted that planets have histories. That they are born, age, and die. But there was not yet appreciation they can have very different histories. The assumption, instead, was invariably that the Solar System’s rocky planets simply embody earlier and later versions of one developmental story.

Indeed, at this time, it was thought our Solar System originated from a nebula collapsing in on itself. The planets — in sequence, from the outer rim inward — were thus supposedly born during this gradual compaction. The outer planets were supposed older, and the inner ones younger, with Mercury being the baby of our celestial family.

Where Mars, being farther from the sun, was our planet’s senior, Venus became its junior. Where desiccated, decrepit Mars — a universal desert — was presumed to represent a future stage of Earth’s biography, Venus was seen as a juvenile version of Earth.

Note that assuming every world represents earlier and later permutations of one biographic arc doesn’t accommodate sensitivity to the ways a planet’s unfolding history can be made to change course. There wasn’t yet appreciation that certain events might alter the trajectory of a world, forcing its entire future to change track, hinging on actions or accidents in the present.

It is, of course, also no coincidence this was an era long before widespread receptivity to the suggestion that, here on Earth, human industry might be currently causing something similar to take place.

Nonetheless, presuming Venus to be a younger Earth, it became common during the decades straddling the 1900s to imagine it passing through something resembling our own Mesozoic era. Swampy and sweltering, covered in jungle: hence also, inevitably, the presence of prehistoric reptiles.

Of course, evolutionary theory was, by now, widely accepted. But the suggestion that evolution won’t everywhere lead to similar results was not. It took several more generations for inquirers to fully extrude this further lesson from Darwin’s teaching.

Dinosaurs on Venus

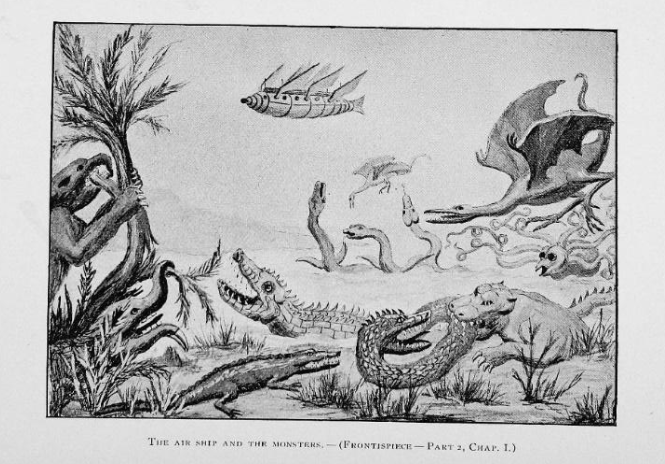

Probably the first to depict Venusian dinosaurs was a Victorian novel called Journey to Venus from 1895. Perfectly encapsulating the era’s attitudes, all the protagonists want is to butcher the lumbering beasts.

Not long afterward, Venusian dinosaurs slithered their way into more serious scientific theorizing. By 1924, Popular Science Monthly was pronouncing our neighbor “may be luxuriant with vegetation and dominated by monsters.” Illustrations accompanied this declaration, including one denizen of Venus markedly more dragon than dinosaur, complete with fiery breath.

The American Weekly, five years later, likewise reported our “younger” twin planet is populated by “enormous dragonflies,” “gigantic crawfish,” and “ammonites.” These latter, readers were assured, will eventually “shake off their shells” to evolve into octopuses “of the earthly type.” Once again, history and evolution were assumed to have only one track. But, of course, dinosaurs were here the main attraction, those “undisputed masters” of Venus.

The longing for dinosaurs luxuriating on a tropical Venus continued well into the 1940s. Children’s books repeated the adage every planet represents earlier and later phases of one “life-history,” before reiterating that Venus, being “youthful,” will host beasts “long extinct on Earth.”

In 1950, a man sent a letter to New York’s Hayden Planetarium, putting himself forward as an applicant for a rocket trip to Venus. He was desperate to go, he explained, because he yearned to find out whether “there are really dinosaurs living on it.”

Now that the Space Age was simmering, Venus could be recast as a tourist destination. Brochures were mocked up, enticing prospective visitors with zoos and “big game hunting” — thus renewing the Victorian dream of hunting dinosaurs to extinction all over again.

Venus flyby

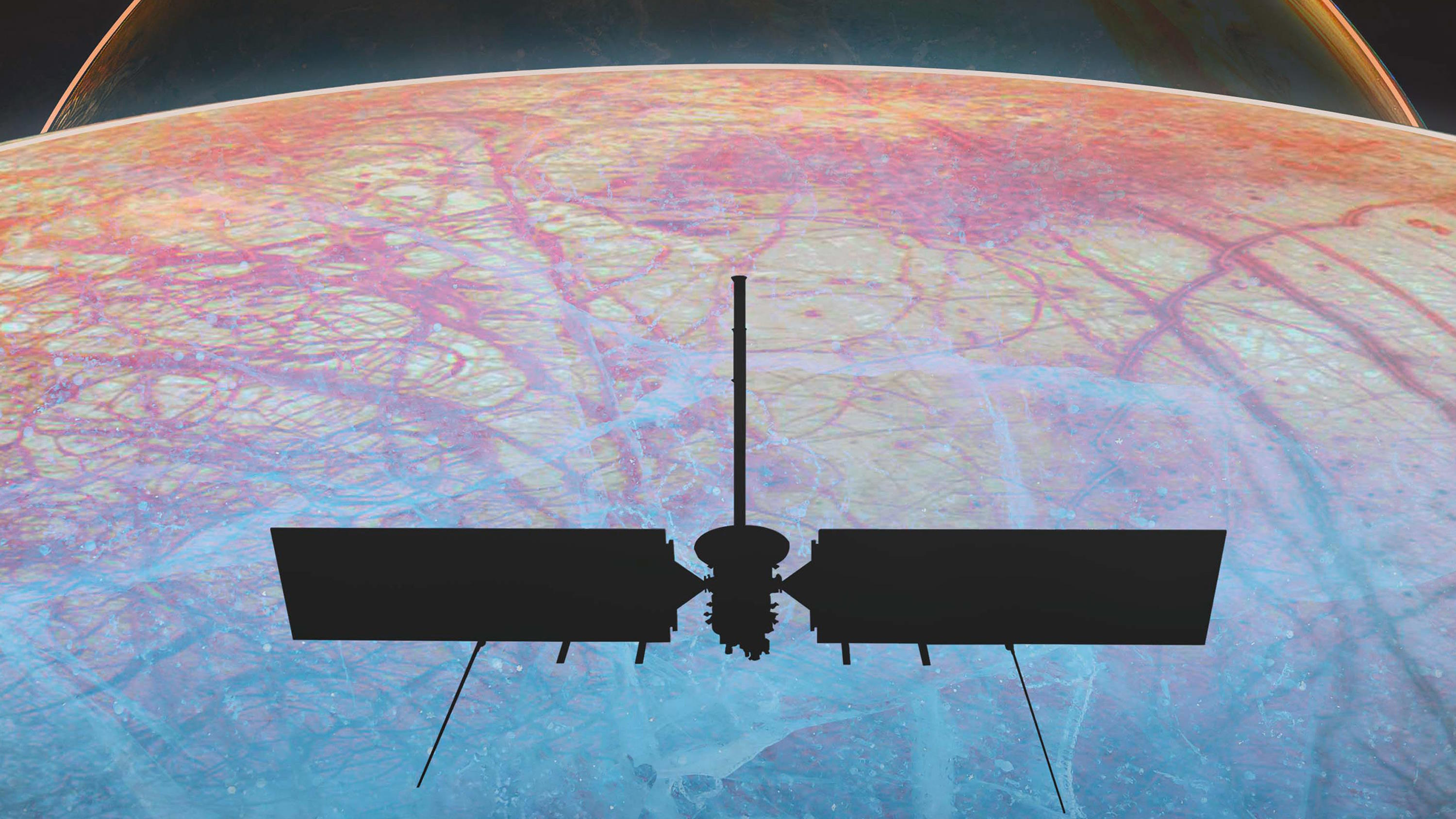

But the bubble burst one fateful day in 1962. On December 14, NASA’s Mariner II probe streaked within 35,000 km of Venus. This was humankind’s first successful flyby of another planet, spurred by the Space Race, now in full swing.

As Mariner’s data beamed back to Earth, people clung to hopes for signs of life. But this rapidly became untenable. In February 1963, the New York Times relayed the bad news: “300F Reading on Venus Indicates No Life There.” Mariner II, shockingly, had revealed our neighbor to be an utterly inhospitable hellscape.

Though some had previously inferred this might be the case, here was undeniable confirmation. When, in 1967, the Soviet Venera IV Probe became the first mission to enter the Venusian atmosphere, and alight on its surface, this was further affirmed. Venus is hell. Not only is its surface hot enough to melt lead, it is also fearsomely pressurized.

Mournfully, dreamers had to say goodbye to their favorite destination. The science fiction author Brian Aldiss published a miscellany in 1968, gathering gems from the now-defunct genre of wondrous Venusian jaunts. Its title: Farewell Fantastic Venus!

Earth’s climate future

It didn’t take long for scientists to start conjecturing our twin wasn’t always so hellish. In the Solar System’s early days, Venus may have been quite clement, oceanic, even habitable. But, then, something happened to trigger its terrible transformation.

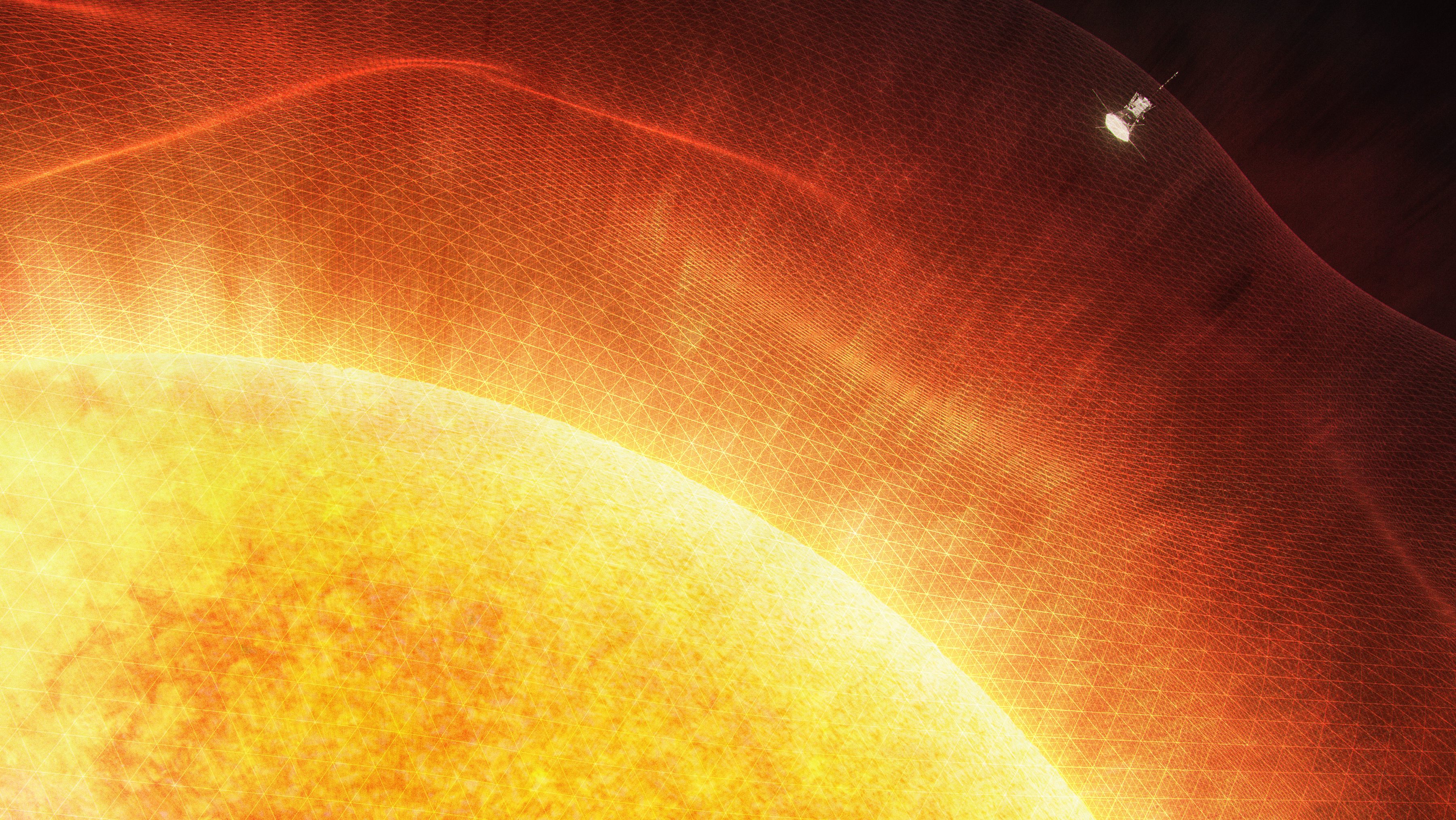

Andrew P. Ingersoll provided an explanation in 1969, becoming the first to adumbrate a model for what we now call a “runaway greenhouse.” This delineates a process whereby increases in temperature cause water to evaporate, creating a moist atmosphere better at retaining heat, and triggering temperatures to continue rising in a reinforcing loop.

So it was that Venus, once a cipher for Earth’s deep past, shapeshifted into a warning regarding our future. Indeed, the revelation that our sister planet is a pressure-cooked hellscape proved that planetary histories don’t everywhere unfold according to the same predetermined script. Which implied, in turn, that a world’s trajectory can be altered, perhaps catastrophically, in wildly diverging directions, in ways not dictated by implacable destiny.

Since the 1900s, scattered voices argued that, by emitting prodigious amounts of CO2, human industry might be perturbing our planet’s atmosphere. But concluding we should do anything remained far from mainstream. Yet, in a very timely manner, Venus provided a cautionary tale.

By 1973, Carl Sagan was urging it is “of first importance” to understand our neighbor’s history to avoid “an accidental recapitulation” here on Earth. Isaac Asimov soon made similar noises. Other experts concurred, remarking that studies of Venus had “opened up the possibilities of runaway on Earth.”

We can’t be sure, but more recent investigations imply CO2 emissions alone likely cannot trigger “runaway” on Earth. However, Venus’ example nonetheless provoked a deeper appreciation of the sensitivity of planetary atmospheres, fomenting investigation into what the worst-case terrestrial scenarios might be.

So, this is how, through being forced to say farewell to fantastic Venus, we discovered climate change on Earth.

Ultimately, it is a hopeful story. Indeed, sometimes, today, climate problems can seem insoluble. But only through looking to our past can we gain any proportionate sense of humankind’s potential to learn and become better at conducting ourselves collectively in this world. After all, only a century ago, there were velociraptors on Venus. Then, through probing our Universe, and toppling this wistful belief, we became aware of a big problem close to home.

Solutions will be far from simple. But becoming aware of an issue is the first step to finding a fix. This way, looking to the past nurtures sparks of hope for our future.