The 1920s plan to make criminals confess to a terrifying skeleton

The 1920s were a dramatic time for American courtrooms. In 1921, the entire 1919 Chicago White Sox team was charged with purposefully throwing the World Series. The Scopes Monkey Trial dominated national newspapers in 1925. And the Sacco-Vanzetti case, and its accompanying appeals, divided the nation for years.

Courtrooms of this era might have been even more exciting, though, if law enforcement officials had taken the advice of one Helene Adelaide Shelby of Oakland, California. Shelby’s innovative idea: what if someone besides an ordinary detective oversaw criminal justice-related interrogations? What if, for instance, the questioner was a giant skeleton with glowing red eyes and a camera hidden in its skull?

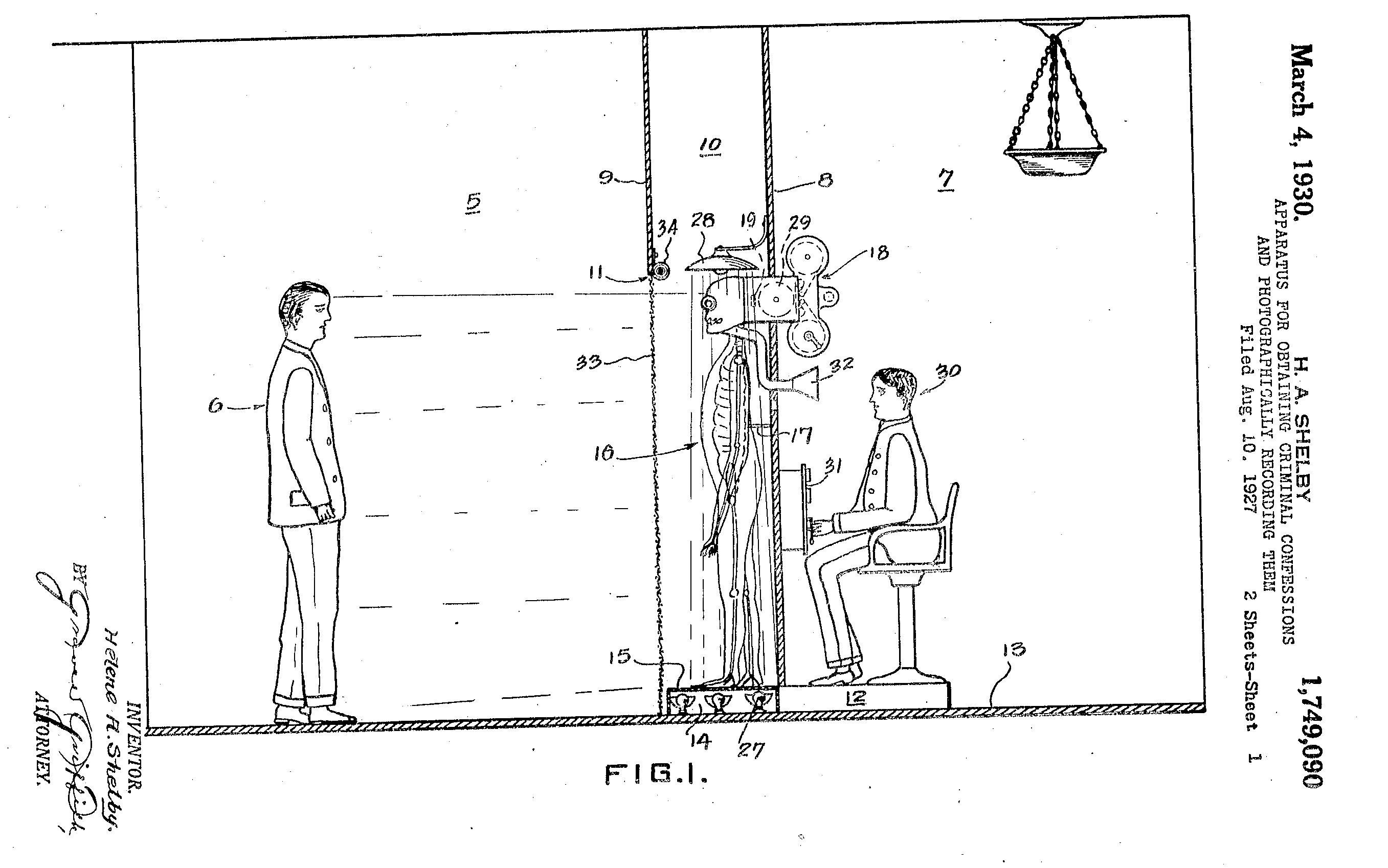

U.S. Patent #1749090, a.k.a. “Apparatus for obtaining criminal confessions and photographically recording them,” was filed by Shelby on August 16, 1927. Her goal was to cut down on retracted confessions: “It is a well known fact in criminal practices that confessions obtained initially from those suspected of crimes through ordinary channels, are almost invariably later retracted,” she explains in her patent application.

Her invention, which she describes as a “new and useful apparatus,” is designed to “produce a state of mind calculated to cause [a criminal], if guilty, to make confession thereof,” as well as to record that confession.

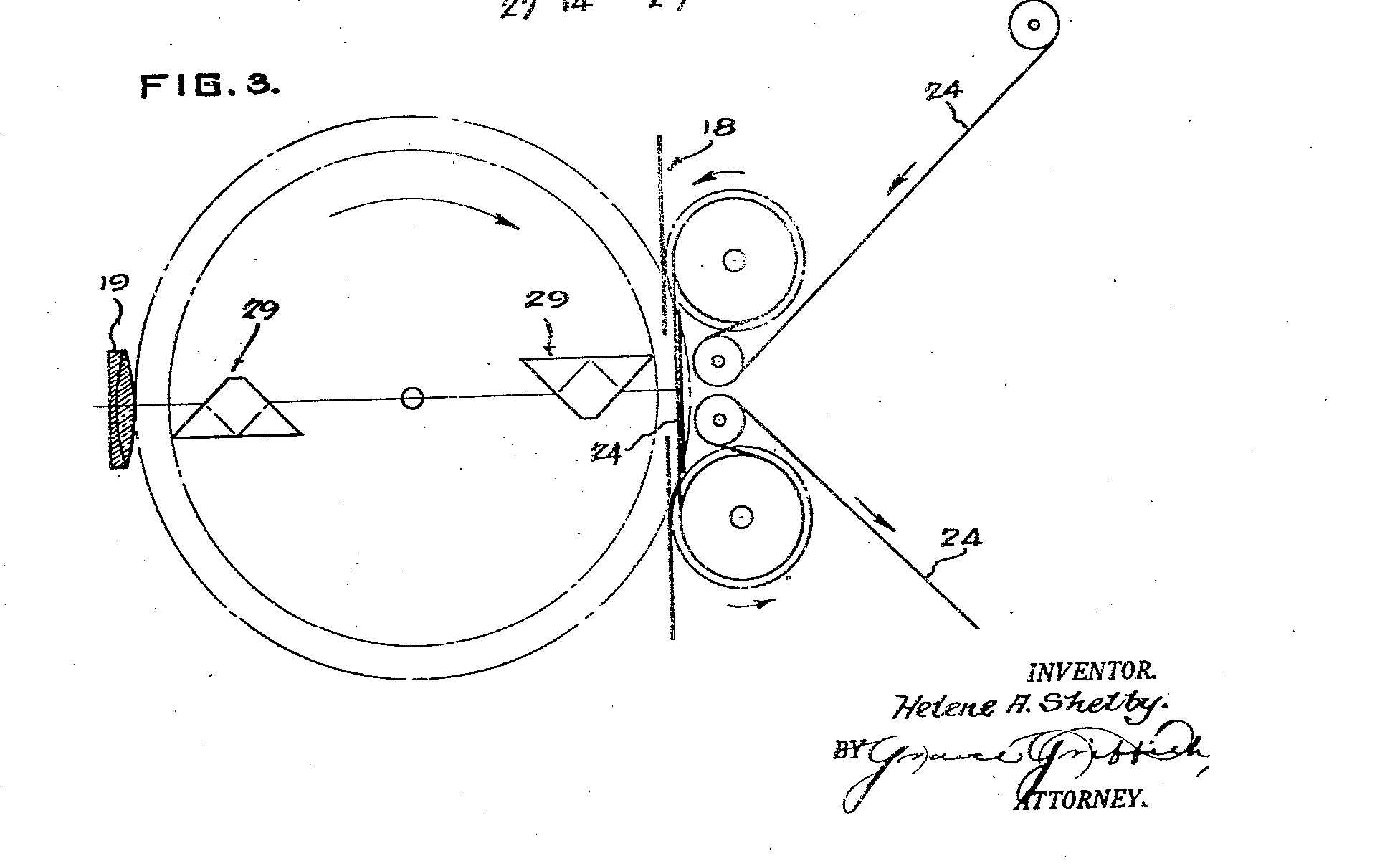

Straightforward enough, right? The twist is, as always, in the execution. Shelby’s invention works like this: first, the suspect is confined in a small, dark chamber. (In the accompanying illustration, this ne’er-do-well is a bemused-looking man in cuffed pants, standing upright—all very suspicious.) The examiner, who is in charge of eliciting information from the suspect, sits in a second, attached chamber, and asks his questions through a megaphone.

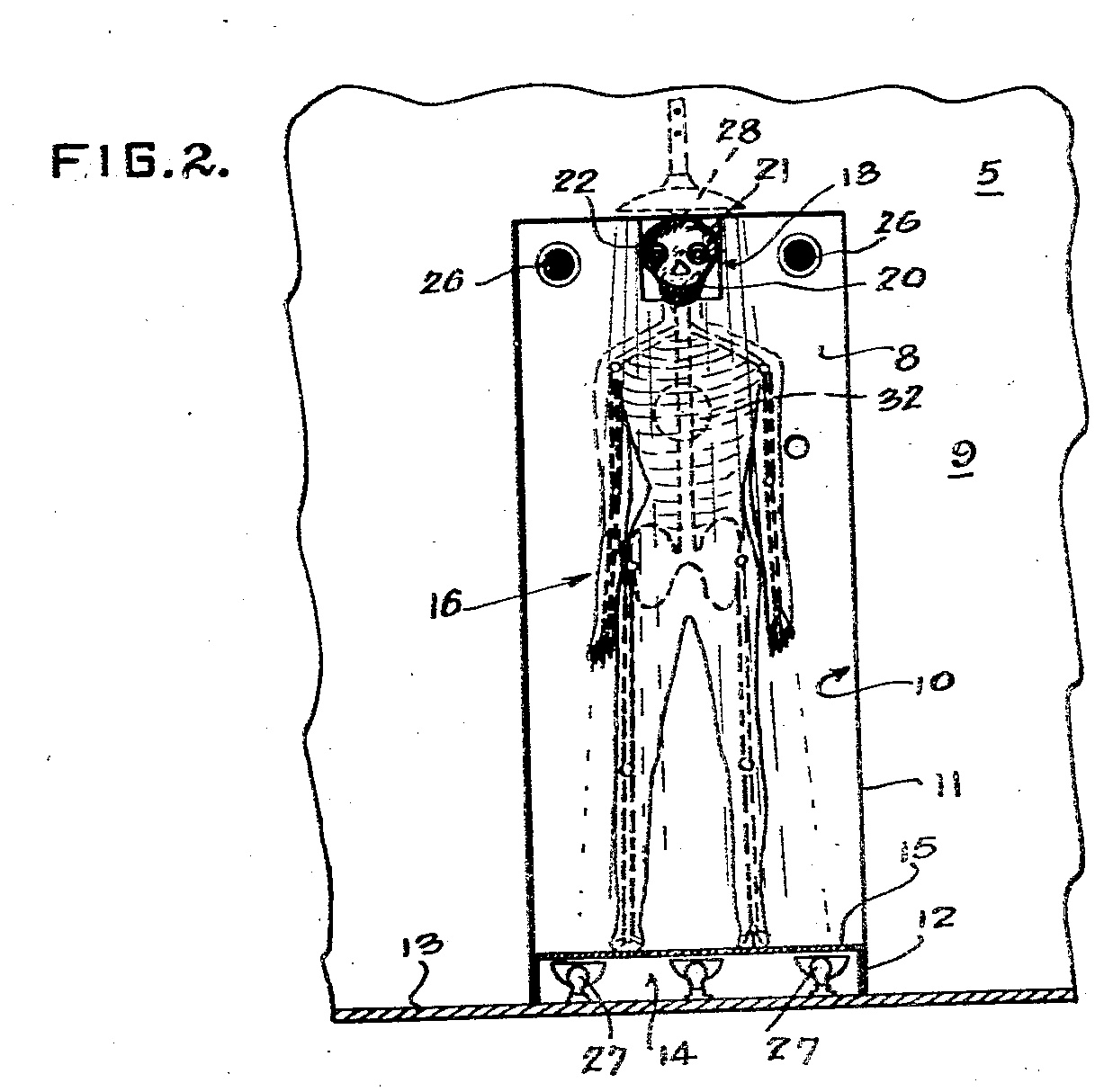

The suspect cannot see his human questioner, though. Instead, as soon as the examiner flicks a button, a curtain lifts within the chamber, and the unlucky interrogee is suddenly faced with “a figure in the form of a skeleton,” surrounded by a “diaphanous veiling” and illuminated from both above and below by “a plurality of electric lights.” This light-and-curtain scheme is designed to make the skeleton seem like an apparition, as though it has spontaneously arisen inside the confession booth.

The skeleton’s eye sockets contain red lightbulbs, “for the purpose of importing… an unnatural ghastly glow,” and the megaphone is positioned “in such a manner that the voice of the operator appears to come from the mouth of the skeleton.” (It also blinks.)

Effective? You bet. These “illusory effects… of a supernatural character” Shelby writes, will “work upon [the suspect’s] imagination.” Convinced that he is speaking to a true ghost skeleton, the bandit in the chamber will spontaneously confess his most secret crimes.

But that’s not all! While the suspect is spilling his guts to the skeleton, the skeleton is recording the suspect via a film camera installed in its skull. Said camera is a nifty machine that, as Shelby explains, can “photographically and simultaneously record both scenes and words,” in the form of pictures and a corresponding audio recording. The examiner operates the whole shebang via a handy switchboard.

Later, if the criminal attempts to retract his testimony, the pictures and audio, which “depict [his] every expression and emotion,” can be marshaled as evidence.

Who was the woman behind this twisted piece of genius? A search for Shelby’s name in newspaper archives reveals only a few hints about her life: she was a bit of a real estate maven, selling and leasing properties in Oakland, Santa Cruz and San Francisco. She occasionally bet on horse races, and she died in 1947, leaving behind a husband, Edgar. Invention-wise, she was a one-hit wonder—she has no other patents on file. It doesn’t seem as though anyone ever built her skeleton-based interrogator, either.

That’s probably for the best. In 1961, the Supreme Court ruled that coerced confessions are not admissible in court—although, as the legal scholar Saul Kassim wrote decades later, “there is no simple litmus test” for what counts as coercion. If anything qualifies, though, a secretly surveilling, dramatically lit skeleton might just be it.

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.