The strange case of Benedetta Carlini: how the Catholic Church investigated fraudulent saints

- In medieval times, the Catholic Church used a routine procedure to determine whether someone was a genuine mystic.

- Renaissance historian Judith Brown outlines these procedures in her book Immodest Acts, which follows the investigation of Theatine nun Benedetta Carlini.

- Carlini claimed Christ asked her to marry him, but the investigators determined that her visions had actually been conjured by the devil instead.

While digging through the State Archive of Florence, Renaissance historian Judith Brown learned about Benedetta Carlini. Carlini, the archive’s entry read, was a nun from 17th-century Italy who “pretended to be mystic, but who was discovered to be a woman of ill repute.” Some further digging revealed that, after her visions were pronounced fraudulent by representatives of the Vatican, Carlini was found to have fornicated with another nun.

That last bit caught Brown’s attention. Female mystics under investigation by the Catholic Church were often accused of fornication, but almost always with a monk or friar. In the late-medieval world — a time and place dominated by men fearful of female sexuality — lesbianism was so inconceivable that people simply refused to acknowledge its existence. Its rarity in historical documents of the time indicated that Carlini’s path to sainthood was not interrupted by baseless rumors.

In an attempt to better understand the life of this extraordinary person, Brown looked for every reference to Carlini that she could find. The result of her endeavor, a book called Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy, not only elucidates religious and historical attitudes toward human sexuality, but also outlines the procedures and reasoning that the Catholic Church once used to determine whether a person’s prophetic visions were, indeed, the work of God.

Despite being a work of serious and highly relevant scholarship, Immodest Acts reads like a meticulously crafted crime story — a testament to Brown’s talent as both a writer and researcher. Carlini’s story unfolds in the same way as it did in life: chronologically. It starts with her miraculous birth in the Italian countryside and rise as a saintlike figure, and it ends with her downfall at the hands of a religious order that not only questioned her powers but feared them.

The life and visions of Benedetta Carlini

Like any aspiring saint, Carlini’s youth had a supernatural quality to it. She was born in 1590 in Vellano, a sleepy town in central Italy. Her birth was difficult, and when her father was told neither mother nor daughter might survive the process, he promised God that, if they did, he would arrange for the child to become a nun. This was several decades before the Council of Trent determined that women should enter convents of their own volition, not by coercion or predetermination.

At the age of nine, Carlini joined a community of unmarried women living on the outskirts of the nearby city of Pescia. There, under the oversight of Theatine fathers, community members devoted themselves entirely to the service of God. Their daily lives consisted of prayer, fasting, and communal work. The women were prohibited from interacting with the townspeople that surrounded their convent and frequently flogged themselves with whips to recompense for their sins.

It was in this oppressive and isolating environment that Carlini — whom Brown describes as an imaginative person — began receiving visions from heaven. One time, a statue of the Virgin Mary began to move as she was praying. Another time, Christ himself appeared to her in the shape of a handsome young man, exchanging her heart with his own under the condition that she would endure tremendous suffering to prove her love for him.

Initially, Carlini’s superiors were not impressed. Guided by the belief that women were spiritually inferior to men, they warned her that her visions came not from God but the devil. It was not until Carlini showed them tangible proof of her communication with Christ that the rest of the convent started to believe her: One night, rays burst from a crucifix, brandishing the nun with the same iconic wounds that Christ bore when he was nailed to the cross.

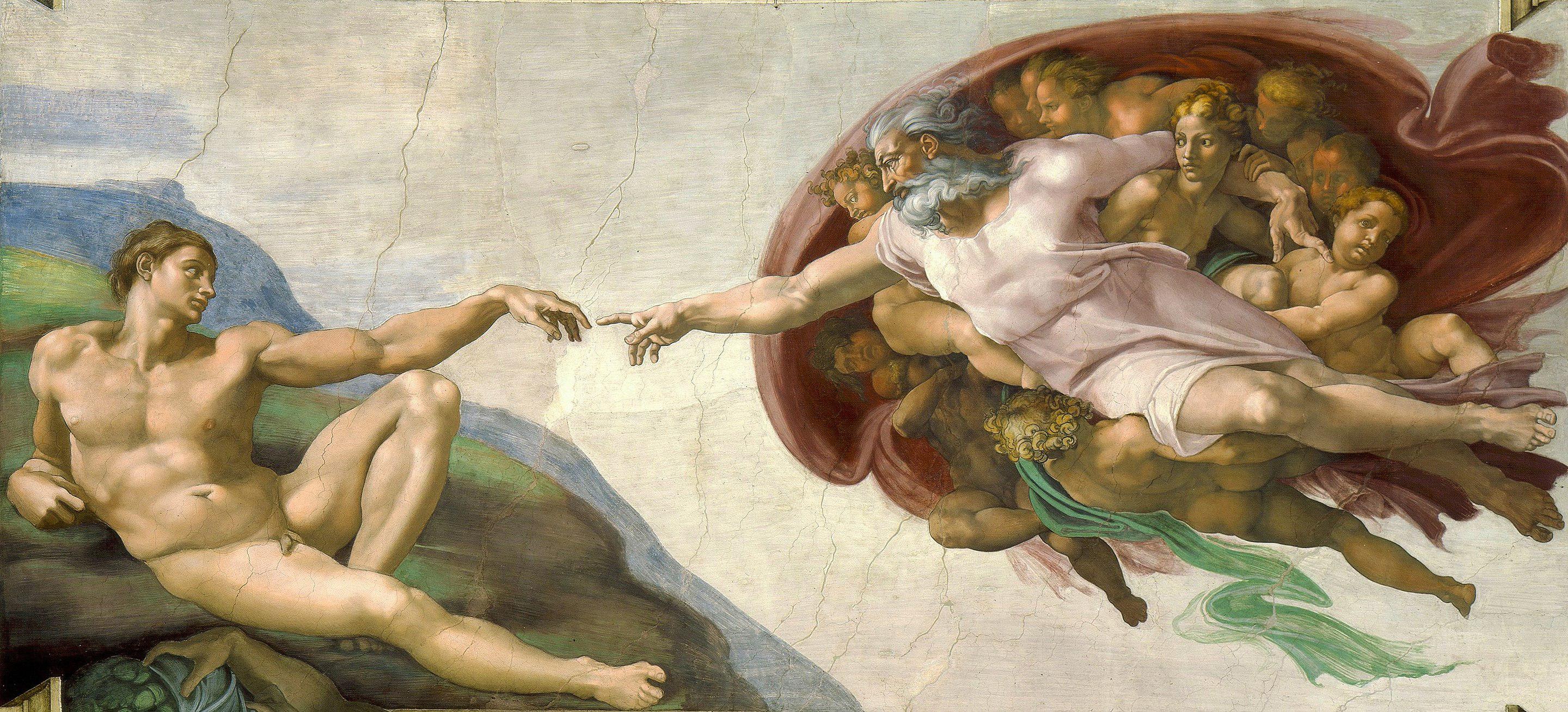

The stigmata, as these wounds were called, were known to have appeared on the bodies of numerous saints, including Francis of Assisi. Her gifts no longer questioned, Carlini was elected abbess of her convent. She also began preaching — an unusual practice, as it was thought shameful for medieval women to speak in church. This sentiment, Brown explains, was derived in part from the Bible (since Adam blamed Eve for his sin).

Wife of Christ on trial

A turning point in Carlini’s life came when, during a vision, Christ asked her to marry him. The Messiah ordered his bride to gather the convent’s nuns and their father confessor so they might witness their union. The nuns thought their invitation meant they would bear witness to another tangible miracle. When this miracle did not take place, the convent once again grew to distrust Carlini, whom they suspected was looking for attention rather than salvation.

At their request, Stefano Cecchi, the provost of Pescia, came to investigate the nun. Such investigations were fairly routine at this point, as the Catholic Church had caught many people “faking” their mysticism. A common method was by painting the stigmata. However, each time Cecchi examined Carlini’s hands and feet, which he did many times over the course of the investigation, they were either covered in dried blood or freshly bleeding.

But the stigmata was not the only means by which sanctity could be verified. In her writing, St. Teresa of Ávila urged Church representatives to study the behavior of the mystic. “The search for mystical experiences,” Brown paraphrases, “was inimical to humility, the most fundamental characteristic of a true seer.” In this area, Carlini had fared well, too. Although she had (speaking on behalf of Christ) often commemorated her own virtues, she acted as his servant, not his placeholder.

A pious Christian, Church representatives reasoned, always recognizes themselves as a sinner. Consequently, visions from God would not fill them with joy or pride but mistrust and confusion. This, Carlini told Cecchi, had been her response as well. In her visions, Christ pointed out her many imperfections, and she spent her waking hours trying to live up to his unachievable standards; she fasted vigorously to purify her body and reduce menstruation, “one of the curses of Eve.”

However, Carlini may have tried to thwart the investigation. Speaking on behalf of Christ, she warned the provost that if he continued, God would unleash the plague upon Pescia. Considering the city was one of the few places in Europe that had not yet been touched by the disease, Brown suspects that Cecchi took this warning to heart. The investigation concluded: Carlini’s visions were officially validated and she was reinstated as abbess of her convent.

The second investigation

Documents are unclear as to how the second investigation got underway, but Brown seems to suggest it had something to do with the way Carlini treated her fellow nuns. As an abbess, she was strict, subjecting the convent to the same rigorous standards to which Christ had subjected her in her visions. She claimed to have briefly visited heaven, a place she learned she was destined to go. The other nuns would go there as well, she said, if they behaved as they should.

This time, the investigation was handled by a higher office within the Church: a nuncio or direct representative of the Vatican. In his investigation, the nuncio employed stricter guidelines than had the provost. Due in part to pressure from the Protestants, the Catholic Church was forced to rethink its definition of a saint. In the past, such a person was recognized through visions and miracles. Now, a saint was seen as someone who had lived an exemplary lifestyle.

In this regard, Carlini was no better than her fellow nuns. The nuncio also noticed a number of theological contradictions in her visions that Cecchi had overlooked. According to official Church doctrine, Christ was an all-powerful entity and, as such, it did not make sense that he had required Carlini to set up a wedding ceremony and convince her convent to attend it. They were also unable to recognize the names of the guardian angels which Carlini said she had been given.

Brown suggests that the second investigation was motivated not only by the ramifications of the Protestant Reformation, but also by the nuncio’s prejudice against Carlini’s hometown of Vellano. “The devil,” Immodest Acts reads, “as was well known, liked those high, isolated places, where Roman Catholicism had gained only a precarious foothold, and where magic and superstition abounded.”

Perhaps figuring that their abbess’ days were numbered, the other nuns came forward with confessions they had supposedly withheld from Cecchi. One had seen Carlini smear a statue of Christ with her own blood, only to tell others that it started bleeding on its own accord. Another had caught Carlini sneaking into the convent’s kitchen late at night to gorge on salami — a favorite food she promised her divine husband never to eat again.

Carlini’s affair with Bartolomea

The most “damaging testimony” came from Bartolomea, a young nun that the convent’s father confessor had assigned to Carlini when she began receiving visions of Christ. Carlini claimed that these visions were accompanied by terrible pains, and Bartolomea was to sleep in the same bedroom in case of an emergency, as well as to offer Carlini comfort and spiritual assistance. Their beds were separated by curtains, which, Bartolomea now attested, Carlini eventually parted.

“The sister Benedetta,” records state, “for two continuous years, at least three times a week, in the evening after disrobing and going to bed would wait for her companion to disrobe, and pretending to need her, would call. When Bartolomea would come over, Benedetta would grab her by the arm and throw her by force on the bed. Embracing her, she would put her under herself and kissing her as if she were a man… And she would stir on top of her so much that both of them corrupted themselves.”

Unable to process something that society had rendered inconceivable, the scribe who wrote down these lines did so with an increasingly illegible handwriting. Benedetta herself, it seems, had also set up psychological defenses allowing her to commit an act that her contemporaries considered sinful beyond measure: Bartolomea explained that, during intercourse, Carlini would assume the identity of her male guardian angel, Splenditello, who professed his divine love for her.

In the late medieval period, people accused of lesbianism were often burned at the stake. Carlini, however, met a different fate. Repeating what her father confessor had told her when she received her very first vision, the abbess now maintained that her powers had been the work of the devil, not of God. The nuncio, driven by the then-common notion that women were more impressionable than men and easily led astray by evil forces, agreed.

Carlini was forced to step down as abbess. The diaries of another nun reveal that she died at the age of 71 after having been imprisoned in the convent for several decades. Her fellow nuns were forbidden to talk to her, but in a final twist of fate, her funeral was attended by laymen who had come from far and wide, eager to bid farewell to the mystic married to Christ. “In the end,” Brown writes, “Benedetta triumphed. She had left her mark on the world and neither imprisonment nor death could silence her.”