A sensational theory about a civilization-ending comet in ancient Ohio has been retracted

- The Hopewell Culture of the Midwestern U.S. developed a sprawling trade network and built monumental ceremonial earthworks between roughly 100 and 500 AD.

- Last year, a team of researchers from the University of Cincinnati presented evidence that a comet airburst, triggering a shock wave and fires, contributed to the demise of the Hopewell.

- More recently, a dissenting team of scientists refuted those claims, insisting instead that the Hopewell Culture simply fizzled out over time as politics, economics, and settlement patterns changed.

Roughly 1,900 years ago, a prominent Native American culture arose in the Midwest, centered in southern Ohio. Though not a true civilization — there were neither large cities nor common rulers — the Hopewell Culture connected communities and tribes living from modern-day New York, across to Minnesota, and down to Missouri.

The Hopewell peoples traded similar trinkets, painted similar art, cremated and buried their dead in similar manners, and, above all, shared a spirituality that drew them all to the Ohio Valley. It was here where they collectively constructed monumental ceremonial earthworks and regularly pilgrimaged to celebrate the religious traditions that united them. They feasted together, practiced elaborate rituals, held funerary services for the highly respected deceased, and watched the young perform rites of passage.

The Hopewell network persisted for perhaps 400 years, until around the year 500, when it unceremoniously ceased. Archaeologists still aren’t sure why. Discord and warfare may have caused the disparate Hopewell to silo themselves away. The introduction of the bow and arrow could have resulted in over-hunting and game shortages. Increased agriculture may have led tribes to become more sedentary and less reliant on trade.

A killer comet

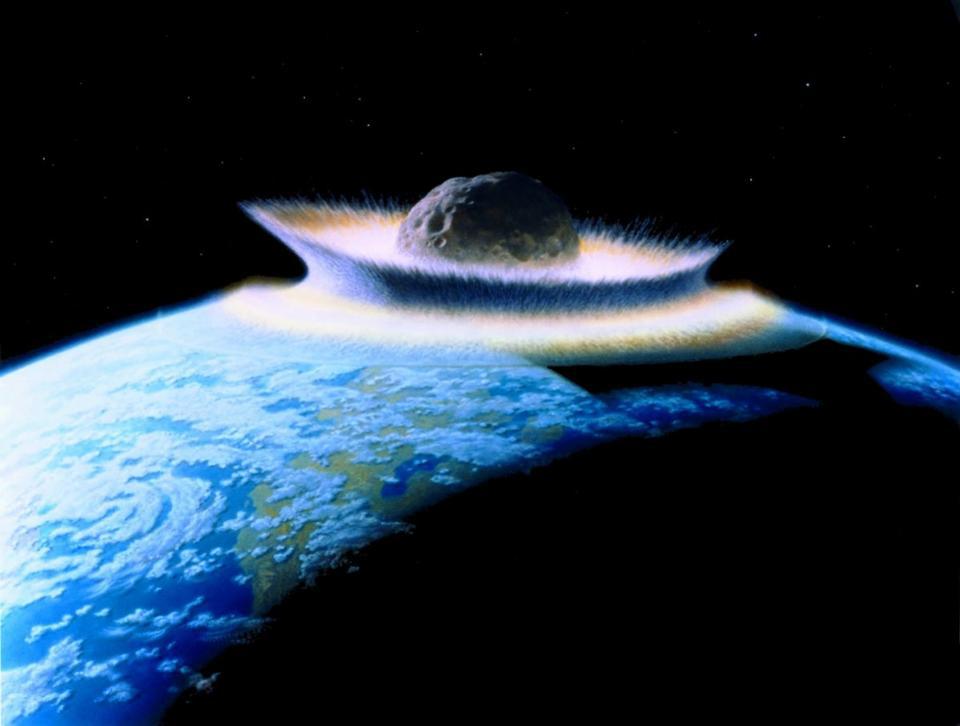

Last year, scientists primarily based out of the University of Cincinnati presented evidence for a different, decidedly more explosive, explanation: a comet airburst. According to the researchers, between the years 252 and 383 AD, a large comet bored through our atmosphere at blistering speeds and exploded over the Ohio River valley, triggering a shock wave that leveled trees, structures, and living creatures while sparking fires across an area as expansive as 15,000 square kilometers.

“While Hopewell people survived the catastrophic event, it likely contributed to their cultural decline,” the researchers wrote. “The airburst event may have created mass confusion resulting in an upheaval of the social interaction sphere.”

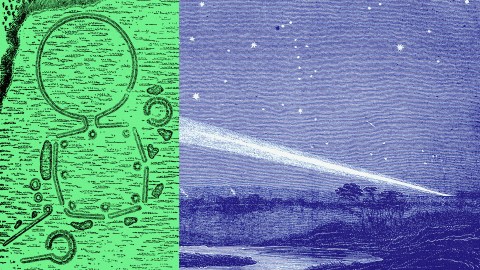

The authors laid out numerous lines of evidence for their hypothesis. First, they noted the presence of meteorite fragments throughout the Hopewell archaeological record, which, prior to their paper, had been reasoned to be acquired from extensive trade. Second, they turned up numerous burned, charcoal-rich surfaces at sites of Hopewell habitation as well as burned wooden structures, which they said evince the blast wave and resulting fires. Third, they found copious amounts of tiny iron- and silicon-rich spherical particles as well as higher-than-normal amounts of platinum and iridium in soil samples taken from the area, both of which are telltale signs of a comet airburst. Fourth, they noted that several Native American oral histories from the time period and region describe a cataclysmic event reminiscent of a comet airburst. The Myaamia people, for example, tell of Lenipinšia, “a horned serpent that crossed the sky and dropped rocks on the land before plummeting into the river.”

The comet theory crashes

The University of Cincinnati researchers’ fascinating tale was covered widely in the media, including at Big Think, but not everyone was enthused. Some experts thought the evidence presented did not substantiate the bold claim. In early August of this year, an interdisciplinary team of anthropologists, archaeologists, meteorite experts, and National Park Service workers at Hopewell Culture National Historic Park in Chillicothe, Ohio published a paper that didn’t mince words with its title: “Refuting the sensational claim of a Hopewell-ending cosmic airburst.”

The body of their work is scathing. The original authors, they wrote, “misrepresent primary sources, conflate discrete archaeological contexts, improperly use chronological analyses, insufficiently describe methods, and inaccurately characterize the source of supposed extraterrestrial materials to support an incorrect conclusion.”

More specifically, the dissenting team of scientists says that the burned surfaces cited by the original researchers as evidence for a cataclysmic blast wave and subsequent fires are simply ceremonial basins, localized burned areas, or burned floors within mounds. They add that the original authors neither conclusively linked the platinum and iridium nor the iron- and silicon-rich spherical particles to the burned surfaces. Thus, they could have originated from some other time. Furthermore, the iron- and silicon-rich spherical particles lack magnesium and nickel, which suggests that they might not be from meteorites and are instead just from the local soil.

The team favors a more mundane conclusion based on decades of archaeological research: The Hopewell Culture and their towering mounds in southern Ohio did not meet a fiery end, but instead simply fizzled out.

Their arguments appear to have resonated with the editors of Scientific Reports, the journal that published the original paper. On August 30th, they retracted it, writing, “The Editors no longer have confidence that the conclusions presented are adequately supported.”