“Russell conjugation”: A rhetorical trick that loads words with emotion

- A “Russell conjugation” can subtly alter the emotional mood of a statement to support an unspoken argument.

- Political euphemisms are prime examples of a Russell conjugation in action.

- While we should feel free to express ourselves, we can also be more responsible in how we scrutinize and use language.

In his 2023 State of the Union speech, President Joe Biden referred to the 2020 election as the “greatest threat” democracy faced “since the Civil War.” During his 2016 election bid, former President Donald Trump promised that he could “make America great again.” Barack Obama claimed the gun lobby holds “Congress hostage right now,” while George W. Bush said, “Al Qaeda is to terror what the mafia is to crime.”

Now, maybe you agree these statements were accurate and maybe you don’t. Either way, that’s not entirely the point. While each president spoke as though simply stating the facts, they were infusing their words with emotional significance and not simply for rhetorical flair. Their goal was to sneak in arguments that would, hopefully, go unnoticed and unquestioned.

This is known as the Russell conjugation (aka, “emotive conjugation”). And while politicians are certainly no strangers to this rhetorical trick, the truth is that we encounter it frequently in everyday life — and even use it ourselves.

Not singing from the same synonym sheet

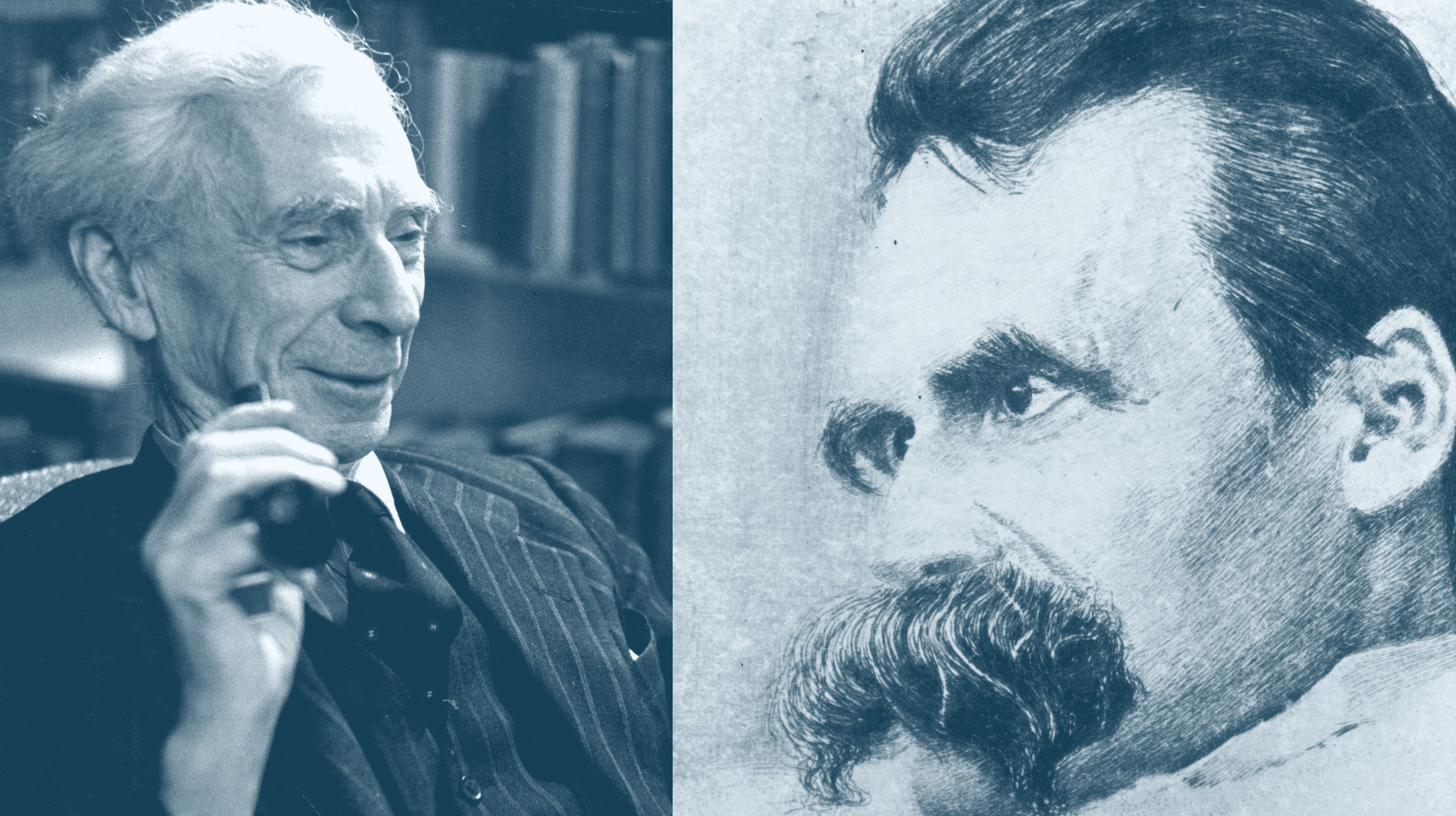

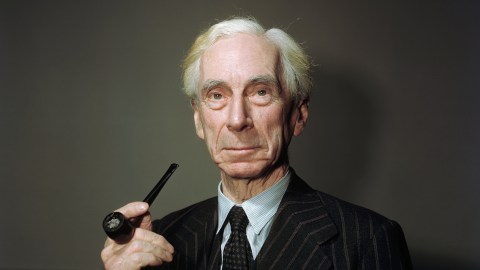

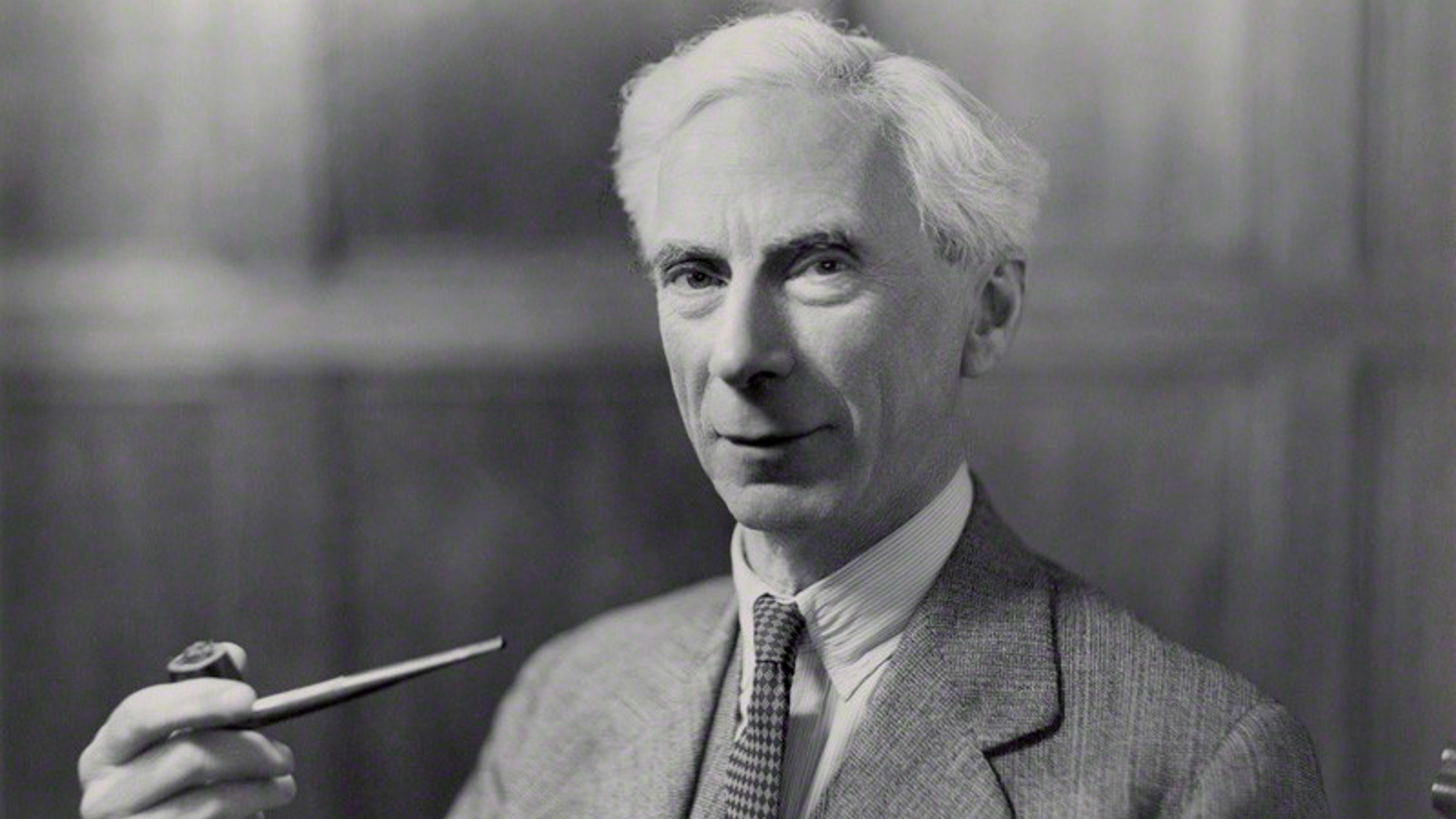

The Russell conjugation takes its name from the philosopher Bertrand Russell. During a 1948 broadcast of the BBC Radio program The Brains Trust, Russell joked that “emotional conjugation” could change the impression of a sentence much like verb conjugation changes the mood. (Yes, that joke is dry even for someone who hung out with analytic philosophers all day.)

While it would be more accurate to call the device an “emotional construction,” the name has stuck in part because Russell offered the perfect expression of it on that program: “I am firm, you are obstinate, he is a pig-headed fool.”

Note how the adjectives in all three statements have the same definition. Each one describes its subject as “stubborn.” With each phrasing, however, Russell simultaneously changes the feelings they evoke. This is known as a word’s connotation. Firm rings with positivity. Obstinate is mostly neutral but with a slight edge of negativity (so, watch yourself). Meanwhile, pig-headed is a straight-up insult even before piling on with fool.

As with the U.S. presidents above, Russell’s three statements are presented as assertions of fact, and they may well be. All three subjects could sport brick-wall levels of intransigence. But by loading his statements with these emotional connotations, Russell has primed the listener to support an argument. That argument being that his stubbornness is advantageous. The other guy’s? Total detriment.

As Douglas Walton notes in the Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation, using this kind of emotional language is “an easy way to get your argument across without it even being challenged or examined critically.”

Conjugation across the nation

As Russell’s example suggests, you can find his emotional conjugations in many assertions that seem innocent at first blush. It shows up in business (my business is course correcting, my competitor fires hard-working people), family relationships (I work hard to support my family, you don’t spend enough time with your kids), and debates of all manner (The death penalty is inhumane, the death penalty is a necessary evil).

“In many cases, a statement is loaded to support one side of a dispute and refute the other side in virtue of a term used in the statement that has positive or negative connotations,” Walton adds.

But of course, it’s politics that has gifted us many of the most salient examples of Russell conjugations. For instance, in U.S. politics, it’s common for people to use either illegal aliens, undocumented immigrants, or asylum seekers to describe migrants crossing the country’s southern border.

Again, the word choice not only changes the emotional tenor of the conversation but also presents an argument for the legitimacy of the act. The former argues that such people are criminals, the latter that they are blameless victims, and undocumented immigrants seeks the neutral middle ground (though you can never please everybody).

No doubt you’ve thought of a few more, such as:

- Positive action versus affirmative action versus reverse discrimination.

- Reproductive health versus abortion.

- Public spending versus entitlements versus handouts.

- Enhanced interrogation versus torture.

In fact, a Russell conjugation can even color how we talk about the people talking about politics. “He is an expert” suggests someone knowledgeable on the subject at hand and whose opinion we should listen to. “He is an elite commentator” is someone who thinks they are superior to others despite their opinion being no better. The person’s credentials haven’t changed, just the speaker’s emotional perspective of that person.

What’s the right frame of mind?

At this point, it may sound as if Russell conjugations are nothing more than shady, self-serving rhetoric. This seems to be what podcast host Eric Weinstein had in mind when he wrote that such emotive constructions shield our rational minds from “understanding the junior role factual information generally plays relative to empathy in our formation of opinions.”

There is some truth to that. Language can frame stories or issues in ways that trigger our biases and influence how we perceive them. In a famous 1981 study, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman found that you could convince people to support a treatment for a hypothetical disease if it saved 200 out of 600 people’s lives. However, tell people the treatment will lead to the deaths of 400 out of 600 people, and they will reject it.

The math didn’t change; only whether the numbers were presented in a positive or negative light.

While the framing effect is real — and has been replicated — we shouldn’t misconstrue it as some kind of language-based brainwashing. Looking at politics specifically, a meta-analysis compiling 138 different studies found that framing had small to negligible effects on how people behave and only medium-sized effects on attitudes and emotions. What really seems to matter is whether the emotional tone of the message matches what people already feel.

As the authors conclude, “Overall, citizens appear to be more competent than some scholars [and/or elites] envision them to be.”

Ultimately, we have to accept that language is more than simply a means of transferring data from one brain to another. Our words can inspire, engage, insult, elate, and entice as well as inform. That’s not a bug. It’s a feature, one that can help us frame situations, coordinate social interactions, and make language enjoyable.

It’s a powerful feature though, and Russell’s point — all the way back in 1948 — is that we must conjugate responsibly.

When listening to other people’s constructions of issues or events, we should always ask ourselves, Is this giving me an emotional contact high? If so, Walton warns us to slow down, scrutinize the language carefully, and distinguish between the neutral facts and the emotions those facts elicit.

For instance, some websites today break down how news sources emotionally frame stories through headlines. These sites then compare how left-leaning and right-leaning media bias may charge the same story with different emotional jolts. These tools can help us see Russell conjugations more vividly.

We should be vigilant in analyzing our own word choices, too. Note that in Russell’s original example, he presented himself in the most favorable terms. That was not an accident; he was pointing out that emotional language often plays directly toward our egos and biases. But once recognized, such biases can reveal places where we may need to seek new evidence, challenge our perceptions, update our beliefs — or be a bit more humble in light of our stubbornness.