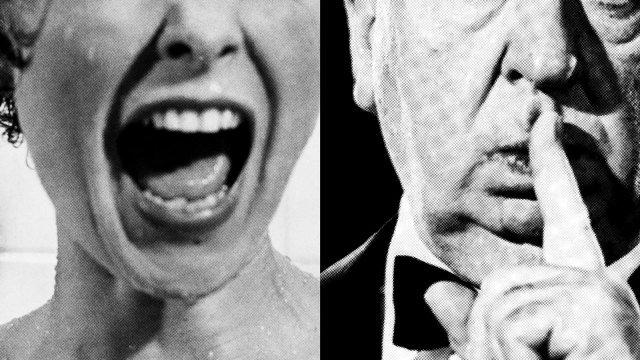

Disarming disinformation: How to understand and counter the “post-truth playbook”

- Misinformation is a mistake. Disinformation is a lie told to cover the truth and spread hate.

- Belief in disinformation is often less about facts and more about tribalism and community.

- To counter disinformation, we can’t give into cynicism or helplessness; we must stay engaged through healthy skepticism.

People have always lied, particularly politicians and those seeking to influence them (and you). According to Lee McIntyre, philosopher and research fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University, many disinformation campaigns today deceive people through reality denial, in which the goal isn’t simply to question particular facts, but to spread distrust of others and stoke cynicism about the very idea of truth.

I recently spoke* with McIntyre about his new book On Disinformation. During our conversation, we discuss the nature of disinformation, who the disinformers are, how their lies spread so virulently, and what we can do about it.

Kevin: Let’s start by laying the groundwork. You emphasize the distinction between misinformation and disinformation. Why is that such an important distinction to make?

McIntyre: If I had five minutes with a microphone that could reach everyone in the world, that is the distinction I would draw. It’s that important.

Misinformation is a mistake or an accident. It’s when somebody says something that isn’t true, and they believe it is, but it just happens to be false. If you show them the evidence, maybe they would see where they were wrong and change their mind.

Disinformation is a lie. It is false information that is intentionally false and shared by someone who knows it is false. And they do it with a purpose. They do it to deceive others into thinking the falsehood is true and to distrust anyone who doesn’t believe that falsehood. So, disinformation can lead not only to false beliefs but also to hate for the other side.

Kevin: So, if I’m under the spell of disinformation, I come to rely on the disinformer, and any new information that comes my way can only be understood and contextualized through that worldview?

McIntyre: You put your finger on something important there. If you are listening to disinformation, the person is not only trying to deceive you but to polarize you, too. That may eventually reach the point where you think, “Well, this is the person I will believe in for everything.” You’ll find yourself in this army of people who are vaccine or election deniers — to pick two random examples — and you’ll no longer listen to the folks on the other side because you believe that they’re lying for some insidious purpose.

People sometimes wonder why they can’t convince somebody who disagrees with them with facts. I think one answer is that it’s not about facts. It’s about trust. If you don’t trust the person who’s sharing the facts, then you aren’t going to believe what they say.

And so, a problem with disinformation isn’t just that it wrecks people’s beliefs. It also wrecks the process by which they form future beliefs.

Kevin: Really makes the cult in “cult of personality” more treacherous.

McIntyre: It does. Because why would somebody share disinformation? When it comes to something like COVID, disinformation could lead to somebody’s death. I mean, what kind of person does that?

The answer is somebody who has an interest at stake. It could be a financial interest or an ideological or a political one. They want what they want, and they’re perfectly happy to victimize other people by telling them false things and having them believe they’re the only truth-teller out there.

A problem with disinformation isn’t just that it wrecks people’s beliefs. It also wrecks the process by which they form future beliefs.

Lee McIntyre

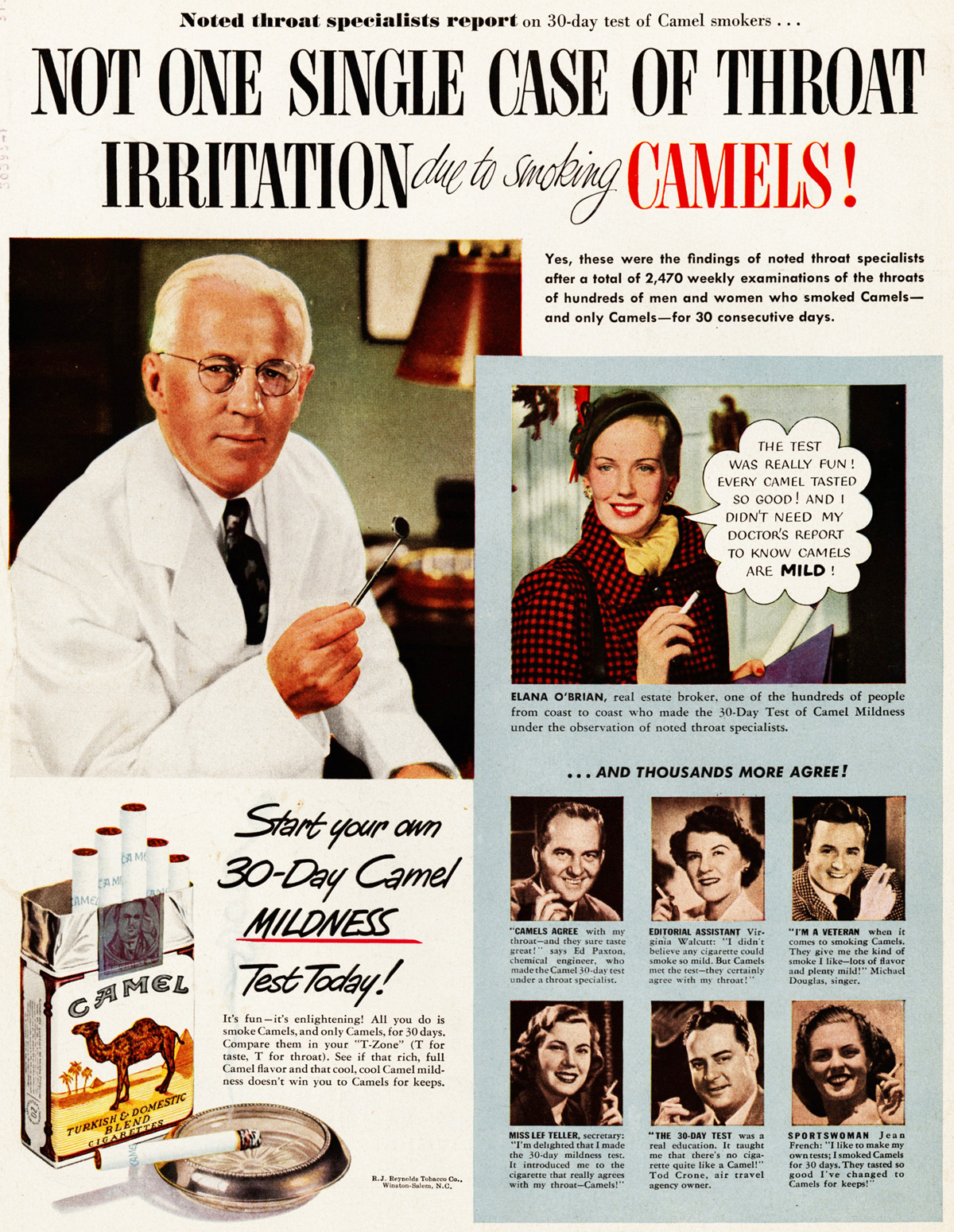

Smoke, mirrors, and cigarettes

Kevin: In your book, you point out that strategic denialism has a lineage dating back to the 1950s and the tobacco companies. Can you walk us through how they developed the “post-truth playbook”?

McIntyre: On December 15, 1953, the heads of the big tobacco companies in the U.S. met at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. They were there to discuss a scientific paper showing a link between smoking and lung cancer. It was going to kill their business, so they hired a public relations specialist to advise them. And at that meeting, his advice was to fight it.

Now, scientists disagree with one another all the time, and they settle their disputes based on evidence. But that’s not what this PR guy was saying. He was saying that, as a matter of public relations, you need to fight the science.

So, the tobacco companies took out full-page ads in newspapers. They hired scientists who did their own research. They did everything they could to make it seem as if there were two sides to the story, to make it seem as if we needed to do more research and not be too hasty.

Why did they do it that way? It wasn’t to prove that smoking didn’t cause lung cancer. It was to get people to doubt something that scientists didn’t doubt. It was to delay, delay, delay — which they did for 40 years and sold who knows how many cigarettes.

Of course, eventually, the memos surfaced that showed they knew they were lying the whole time. They just wanted to make money. When they finally got caught, they had to pay a more than $200 billion fine, the largest settlement in history. Then they went right back to selling cigarettes.

Kevin: If I recall correctly, the tobacco companies have now moved into developing countries and are using the same playbook there.

McIntyre: Yeah. That’s the sad thing; the strategy works.

The firehose of falsehood

Kevin: Do you see today’s spread of disinformation as unique to this moment in history, or is it just the same-old politics magnified through our digital lives?

McIntyre: It’s difficult because politicians have always lied. People have always lied. They say the first conspiracy theory was in Rome around the time of Nero. He was a liar and a tyrant. It goes way back.

But I think what is different today is what you mentioned there, which is the amplification. Because it’s one thing to lie, but now disinformers have websites. They have Twitter. They have the ability to speak directly to millions of people instantly. That’s what really makes it bad. It’s this false information going viral before there’s a chance for the truth to catch up.

You sometimes hear science deniers say, “What about this? What about that and this other thing?” By the time you give them the facts, they have already moved on to something else. It takes so much longer to debunk something than it does for a falsehood to spread. It’s their way of slowing down the other side.

It’s a technique that dates back to [Lenin’s] Cheka: the firehose of falsehood. The disinformer doesn’t give one falsehood. He gives 20, even ones that contradict the others. That way, people have to go, “Whoa, I’m going to have to really sit down and think about that.” Meanwhile, he’s still out spreading falsehoods and evading accountability.

Because where there’s no truth, there’s no accountability.

Lee McIntyre

Kevin: I see. So, if my internal truth machine is based on what a disinformer says, those contradictions can’t be contradictions. That leaves me to wrestle with reconciling those falsehoods while the disinformer just keeps on going?

McIntyre: Exactly. Because the disinformer doesn’t care.

That technique, the firehose of falsehoods, is also meant to make people cynical. To make them think they can’t even know the truth. Because where there’s no truth, there’s no accountability.

Kevin: That connects to another quality of disinformation you mention in your book: When people reach their conclusions without facts, facts won’t change their mind. It’s more about community and values.

McIntyre: Yeah. Disbelief can be a strong bond builder between people. You want to be with your tribe, the people who believe what you believe.

I went to a flat-Earth convention, and what a tight group that was! It was a celebration to see one another in the flesh because they were so alienated from what they called “the normie culture.” They were ecstatic. It was a strong bonding experience for them.

The most trusted names in news

Kevin: We’ve talked about the creators of disinformation, but there are two other variables to this equation: the amplifiers and the believers.

Let’s start with the amplifiers. Who are they, and what role do they play?

McIntyre: There are truth killers, but there are also truth-killing accomplices. That’s where the amplifiers, such as partisan media and social media, come in. The reason they are so dangerous is because you don’t have to be a disinformer to do real harm. They can amplify someone else’s lie and even think they are doing it for a good reason — such as examining it or for the sake of being fair.

Why do they do that? Journalists are allergic to the idea of being accused of political bias, and the easiest way not to be accused is to let both sides talk. But that’s “bothsidesism,” and people know this now. You don’t let both sides talk when NASA launches a rocket. You don’t have a split screen with a flat Earther commenting, “All that didn’t really happen.” You just don’t do that.

But the media want engagement. They want people to not turn off the TV or to keep reading. And so they can be skewed in a way.

It’s the same thing for social media — I mean, talk about privileging engagement! It’s what their algorithms do, and they have control over it. Just before the 2020 election, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube changed their algorithms and started putting disclaimers on, or even blocking, certain disinformation coming down the pike. After the election, they stopped doing that.

I don’t want to come down so hard that I make it sound like the amplifiers are just as bad as the disinformers. They’re not. But it’s painful because they could do something about it. What’s really painful for me is that I think amplification is where we defeat this. You can’t get the creators of disinformation to stop doing it. You can’t really get the believers to stop believing. But if you could stop the amplifiers from amplifying it, disinformation wouldn’t be as dangerous.

True believers

Kevin: Let’s pick up that final variable: What do we need to know about the believers of disinformation?

McIntyre: The believers are victims. Usually, they’re people who are being taken advantage of. Go back to the cigarette example. The people who believed the tobacco companies were the victims. They were the ones who continued to smoke thinking there was a scientific debate, and they died.

I wrote a whole book titled How to Talk to a Science Denier, and it’s about how to have a dialogue with flat earthers, climate deniers, anti-vaxxers, and anti-evolutionists. I think that having that kind of dialogue is really important because you don’t just want to cut somebody off and say, “Oh, they don’t believe what I believe, so to hell with them.”

You have to talk to them while recognizing that facts aren’t necessarily going to change their mind. But by talking to them with patience, respect, and listening, they begin to trust you.

However, the solution to our disinformation problem cannot be to convince all the believers that they’re being lied to. You can’t get ahead of that. You also have to choke off the amplification.

I look at it kind of like an epidemic. You have to try to heal the sick, but you also have to try to keep other people from getting sick. If all you do is try to attend to the sick, you’re never going to get ahead of it.

Kevin: I like that approach. It taps into that idea about community and values. Because if you see them as victims, you’re more likely to try to extend that bridge of communal connection versus if you see them as shills or perpetrators.

McIntyre: You’re being empathetic. I mean, a shocking number of people don’t even know a scientist, so why should they trust scientists? My advice to scientists is to get some business cards, hand them out, and say to people, “If you have a question, call me.” That’s reaching out in a human way, and I think it could make a big difference.

Kevin: Oh, I hadn’t considered that before. In my job, I talk with scientists all the time. But most people don’t strike up conversations with scientists in the grocery store check-out line.

McIntyre: They don’t.

The scientific attitude

Kevin: One issue I think truth tellers run into is that the truth is complicated. It also evolves, sometimes quickly, as new evidence and information come to light.

McIntyre: I’m a philosopher of science, and I wrote a book called The Scientific Attitude where I make the argument that what’s really essential about science is not its method or its logic. It’s the ethos behind science, which is the idea that you care about evidence so much that you’re willing to change your mind in the face of new evidence.

Now, there’s the temptation, especially when you’re talking to a denier or when it’s a public health emergency, to say, “This is true. We have the proof. Go out and do what we say.” That’s dangerous because once trust is lost, it’s almost impossible to get it back.

So, my advice to scientists is to lean into the idea of uncertainty. That doesn’t mean that you have to say, “Well, we don’t know, so go ahead and take your hydroxychloroquine to prevent COVID.” Just because you can’t prove something with 100% certainty doesn’t mean that every hypothesis is equally valid. Some hypotheses are better warranted by the evidence than others. And no matter how well warranted a scientific hypothesis is, it could still be overthrown by future evidence. That’s just the nature of the scientific beast. But I think the lay public is smart enough to understand that. In fact, that builds trust.

Scientists should be able to say, “Look, we don’t know everything, but here’s what we think we know, here’s the evidence, and here’s what we’re still working on.”

But it’s hard. When the hot lights are on you, it’s difficult to admit you’re not 100% certain. And I have such reverence for scientists that I don’t want to make their jobs harder, but when I’m speaking to a scientific audience, I say don’t pretend to know what you don’t know. It’ll come back to bite you. Instead, lean into uncertainty. It’s a noble thing. It’s what makes science so successful.

Fighting disinformation

Kevin: I always like to end these interviews with some actionable advice. So, two questions for you to wrap up.

First — and this is the one that keeps me up at night — how can I tell if I’m under the spell of disinformation? After all, I don’t know what I don’t know. Is there a kind of thought audit I can take myself through?

McIntyre: Okay, here’s what not to do: Don’t become so skeptical that you don’t believe anything. That is, in some ways, what the disinformers want. Another goal of the firehose of falsehood is to get you to think that any of it could be true, so you stop using your brain.

To be reasonably skeptical, when somebody tells you something that you can’t verify for yourself or they don’t have evidence for, ask yourself why they want you to believe it.

One book that has really changed me in this regard is The Handbook of Russian Information Warfare. It’s available through NATO. You can get a free copy online, or you can write NATO, they’ll mail you one. It’s a training manual for NATO soldiers to understand how Russians use information warfare. Now, this may not help you sleep. It’s scary stuff, but it is an important book because reading it is like looking at the opponent’s playbook.

Disbelief can be a strong bond builder between people. You want to be with your tribe, the people who believe what you believe.

Lee McIntyre

I’ll give you an example: Everybody has heard the falsehood that there are microchips in the COVID vaccines. But what people don’t know is that that was a Russian disinformation campaign. So, when you hear there are microchips in the COVID vaccines, maybe you ask yourself, “Why would anybody want me to believe that? Because they don’t want me to take it. Why not? Maybe because they have a competing vaccine, and they want to make money.”

Well, those were the two motives, and you can trace it back. The story came out of a Russian troll farm and was published in its online publication called the Oriental Review. In April 2020, one month into the pandemic, it ran a story claiming that any future vaccines developed in the West will have microchips in them — courtesy of Bill Gates, who holds patent 060606.

Obviously, that’s absurd, but at the bottom of that story, it said “share on Facebook and Twitter.” By May 2020, 28% of the American public believed it.

So, the wrong way to be skeptical is to not believe anything anybody says. The right way to be skeptical is to think, why does that person want me to believe this? Sometimes, the answer will be because it’s true. They are scientists, they’ve studied it, and they’ve got the evidence. But sometimes, they want you to not look very hard.

And the sad part of that story, for me, is that even [after] the Wall Street Journal got to the bottom of it, people still don’t know where that disinformation came from.

Kevin: Last question: How can we counter the post-truth playbook? What are some plays we can run on our own?

McIntyre: One of the goals of disinformation is to make you feel helpless. As though, there’s nothing you can do to fight back against it. That’s wrong. The last chapter of On Disinformation has 10 things that you can do to fight disinformation, and I’ll tell you the most important one: It is impossible to win a disinformation war unless you realize that you’re in one.

Now we’ve come full circle because every time a news commentator uses the word misinformation when they mean disinformation, it makes us realize this was intentional. If there’s a lie, there has to be a liar. Being able to use the word disinformation and admit that we’re in an information war is enormously important. That’s the only way you can win.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

*Note: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.