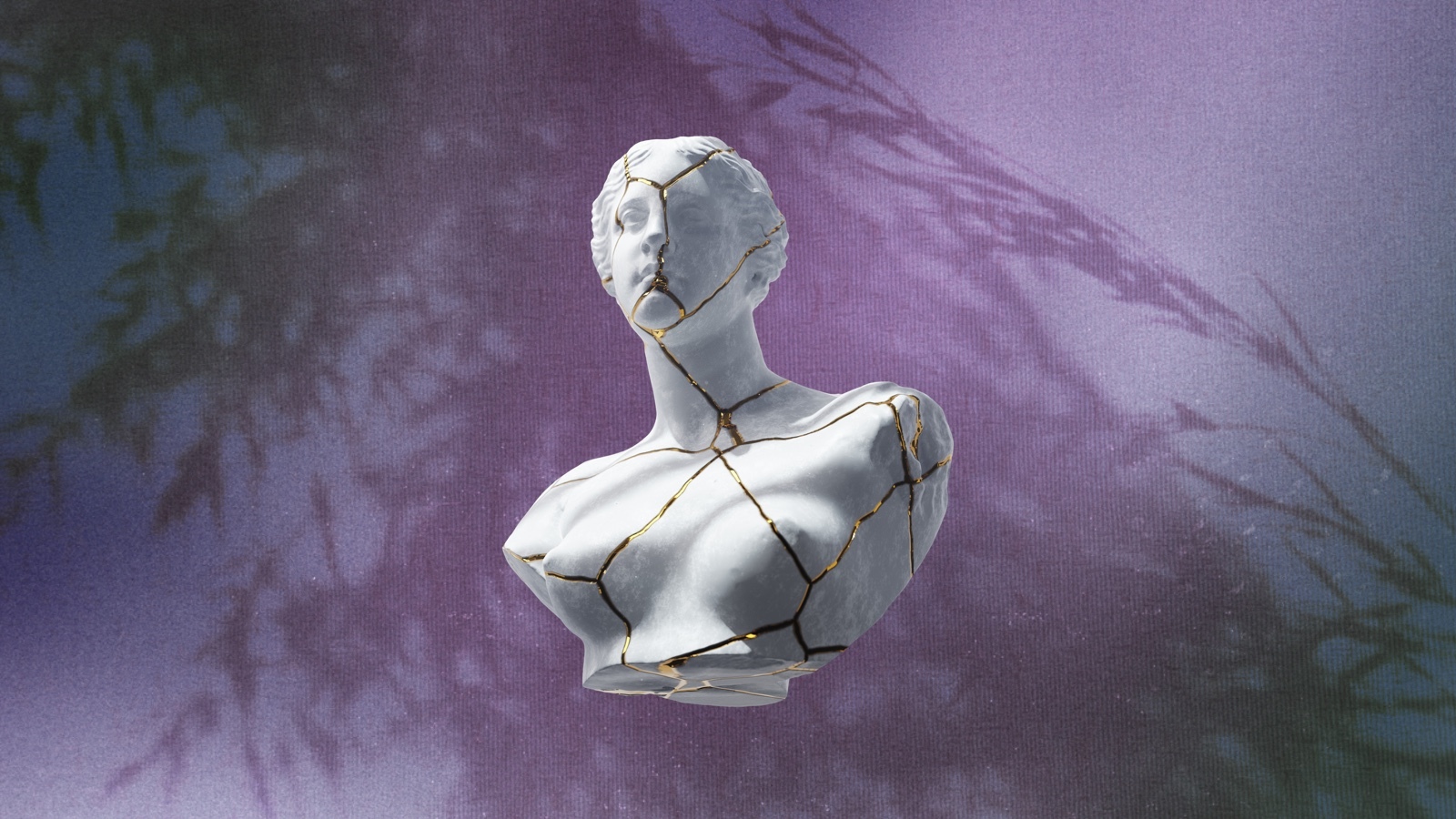

Nagomi: The Japanese philosophy of finding balance in a turbulent life

- It can be difficult to find a sense of balance in the turbulence of modern life.

- Kenichiro “Ken” Mogi believes the Japanese philosophy of nagomi can help people cultivate a greater sense of harmony.

- Nagomi is about blending seemingly disparate elements until they form a unified, harmonious whole.

Finding balance in life can be difficult. Sometimes, it feels like we are fighting invisible forces pulling us in different directions. We work to make a living, but then find we don’t have the time to enjoy life. There are novel diets to try, better habits to form, and social ills to solve. Then there is the ever-present question of how much we can change something — about ourselves, our relationships, and even our society — while still being true to what we valued about it in the first place.

And as soon as we seem to have it figured out, our lives are upended, the world changes, and we have to restart the whole process. How can we not only discover but also preserve that sense of harmony we so desperately seek?

Kenichiro “Ken” Mogi, a senior researcher at Sony Computer Science Laboratories and a visiting professor at the University of Tokyo, believes that Japanese culture has incubated a philosophy of life to help us answer that question. It’s called nagomi, and through it, we can better realize that balance isn’t about finding the one correct direction. It’s about discovering how we can blend life’s disparate elements in ways that work for us — a unifying act that, depending on the context, can take on subtle nuances.

I recently spoke* with him about what that means and how we can cultivate nagomi into our lives.

Kevin: You’ve published many books in Japan, and you’ve recently been writing about Japanese philosophy for other markets. Your first book was on ikigai — that is, how one can find purpose and joy in life. Your most recent is about nagomi.

To lay the foundation for our readers, what led you to explore the Japanese philosophy of life and bring those ideas to other cultures?

Mogi: In Japan, I have been publishing books mainly on neuroscience, consciousness, and self-help in addition to a few fiction novels. When it comes to publishing in English, some books from Japan, like The Book of Tea and Bushido, did really well in the West and elsewhere. Since then, I think there has been a vacancy of books on the Japanese philosophy of life. Of course, Marie Kondo’s books are wonderful, but from the Japanese perspective, they represent a wonderful but partial part of that philosophy. I wanted to do a more comprehensive coverage.

Kevin: For my own curiosity, why start with ikigai before nagomi?

Mogi: The ikigai book was commissioned by the UK publisher. They were looking for somebody who could write about ikigai in English, which is probably a short list in Tokyo. [Laughs.] Japanese people are not known to express themselves freely in English. That’s why I wrote about it. It’s quite nice that it has been well-received all over the world.

As you know, Japan has been sluggish for the last three decades. So, the Japanese people are kind of losing confidence in their country, so the fact that ikigai is being noticed by people around the world is giving some Japanese people more self-confidence and self-assertion. I think that’s a really nice thing — without overconfidence, of course.

Kevin: Not just ikigai either. Japanese art and culture have really taken off in America. I personally love the movies of [Yasujirō] Ozu and [Akira] Kurosawa.

Mogi: You know, the remake of Ikiru by Kurosawa — the U.K. film Living — was written by Kazuo [Ishiguro] and was nominated for the best script at the Oscars. It didn’t win, but the film is all about ikigai. That film could have been titled Ikigai. [Laughs.]

Kevin: Ikiru is one of my favorites. I adore it.

Mogi: I didn’t write about it in my book because it would have been too presumptuous, but I think that Kurosawa’s film is about ikigai. Definitely.

Nagomi: Finding harmony in diversity

Kevin: Your new book is The Way of Nagomi. It’s a deep concept, but what’s a succinct definition our readers can take away with them?

Mogi: Nagomi is balance. It’s about harmony, sustainability, and agreeableness. It’s a very ancient Japanese word and heavily embedded in Japanese history. That concept of harmony, of things being in balance, is found elsewhere in the world, but in Japan, I think it has reached a level of sophistication that might be an inspiration for others. It’s something unique.

For example, the Japanese imperial household is the longest-running hereditary monarchy in the world. Unlike many other nations, we didn’t have a change of the royal household, and that’s probably due to nagomi. Another aspect is that the Japanese people are very good at being successful but at the same time keeping a low profile. I think that’s also due to nagomi.

Another interesting example: [Japan has] different political parties, but we have seen fewer changes of government in the post-World War II era. The LDP (Liberal Democratic Party) has been ruling Japan, more or less. Some people may say that is because Japan is an immature democracy. We don’t have changes of ruling parties as often, like in the States or the UK.

On the other hand, that is probably because the opposition parties really aren’t the opposition. The proposals of the opposition parties are often taken up by the LDP. Policies go through. There’s a sense of nagomi there.

Kevin: Can you give me an example of nagomi as expressed in everyday life?

Mogi: We have this concept of wayochu. It represents the three main culinary influences in modern Japan. Wa means Japanese, yo means Western, and chu means Chinese. In terms of food diversity, I think Japan is arguably one of the most diverse countries in the world. Even a typical person would think about making a balance of wayochu cooking — nowadays probably Indian, too. It’s how we find a balance between different dietary needs. As you know, Japan is one of the countries where longevity and good health are maintained.

Kevin: It’s one of the blue zones, right?

Mogi: That’s right, and a typical example of nagomi at play is mixing elements of different origins. One wonderful apotheosis of this principle is katsu curry. The cutlet is originally a French meat dish, and curry, of course, is originally from India. Katsu curry is a Japanese dish [that combines those with rice], and it is available everywhere, all over Japan. It is also popular in countries like the UK. I don’t know about the States.

[Author’s note: The katsu in “katsu curry” comes from the Japanese word tonkatsu, which translates as “pork cutlet.”]

Kevin: I don’t know how widespread it is, but there are a few restaurants that serve it in my area.

Mogi: Another example is matcha ice cream. Matcha is very Japanese, and ice cream is very Western. So in the process of modernization, I think the Japanese people mixed them in a nagomi principle, and now we have matcha ice cream, which is really wonderful.

Kevin: It is. I indulge every time I get the chance.

Mogi: The Japanese people have very few taboos [about food]. We feel free to mix things up.

Manga, too. Many people may not realize it, but manga and anime were influenced by American culture, especially anime. Many anime makers were influenced by Disney, but the way Japanese anime was made was on a very low budget, so they had to come up with ways of moving characters with fewer frames per second. That led anime to become an independent genre of animated film. That is very nagomi, too.

So, I think the Japanese people are curious, and they have incorporated many external influences, and through that, they have created a well-balanced and sustainable mix of culture. One of the reasons I think nagomi is so important is that many countries are becoming like Japan. Japan has always imported external influences: Chinese influences, European influences, American influences, and so on. I think the same thing is happening for every nation because we are living in a more globalized world.

The way of nagomi in relationships

Kevin: In the book, you discuss nine areas of life where readers should consider cultivating nagomi. We don’t have time to talk about them all, and I don’t want to spoil the book for anyone, so let’s focus on one in particular: relationships. How can we bring a sense of harmony and balance — that is, nagomi — into our relationships?

[Authors note: The other eight areas are life, food, health, the self, society, nature, creativity, and lifelong learning.]

Mogi: That’s a great question. In Japan, I think the ideal person would be selfless and full of altruism. Of course, everyone is kind of self-centered and wants happiness. But in Japan, self-serving, selfish people have always been disdained. The idea is to serve the community, to play for the team.

The concept of nagomi tells you that altruism is not necessarily self-negation. It’s self-serving. If you do something for others, in the long run, it is good for you, too. This has been supported by evidence from neuroscience in recent years. For example, in the brain, there are reward-related circuits like the dopamine circuit, so altruism is very much embedded in our brain circuits, independent of culture.

If you do something for others, and it can also be satisfying for you, that would be the ultimate lifestyle and one that’s very nagomi. I think it’s the same in the States and elsewhere. People just don’t say it in so many words. I think that’s the difference.

But when I watch American TV — especially Fox News [Laughs.] — people tend to be so self-concerned and so aggressive. You know what I mean?

Kevin: I know what you mean.

Mogi: When I see that, I think there might be other ways to do something that would be more beneficial to you, in the long run, by appearing more reserved and altruistic and community-spirited. I feel that sometimes there’s a huge missed opportunity there. There could be a more nagomi way of doing something for you, your family, your company, and so on. What’s your take?

Japan has always imported external influences: Chinese influences, European influences, American influences, and so on. I think the same thing is happening for every nation because we are living in a more globalized world.

– Ken Mogi

Kevin: I think it goes to the promotional aspect of American culture. You’ve got to be the one people listen to. All eyes have to be on you. That’s how you get ahead.

On the other hand, I recently interviewed Dacher Keltner, and his research shows that when we witness kind acts, we not only feel more connected but enjoy a greater sense of awe in life. So, I think our perception is changing in certain corners. It’s just not diffused throughout the culture as I would like yet.

Mogi: That’s good to know. One interesting twist is that we do not have a celebrity culture like in the U.S. I mean, we have rich and famous people, but they do not show off (typically, I mean). They keep a low profile. Again, if you look at the Imperial Family — the Emperor, Empress, and Crown Prince — they keep a low profile. It’s not like Prince William and Prince Harry. And that’s probably due to this concept of nagomi.

In fact, the earliest mention of nagomi comes from the first Japanese constitution. It’s called the Seventeen Article Constitution by Prince Shōtoku. Actually, Prince Shōtoku is the guy who came up with the branding of “the land of the rising sun.” At the time China was powerful, and Prince Shōtoku wrote a letter to China where he described Japan as the land of the rising sun, which is true for China with Japan in the east. But of course, it angered the Chinese emperor at the time.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Mogi: He was clever. But the first article of his constitution said nagomi is the most important principle in this land.

Kevin: That’s fascinating. Expanding on relationships a bit, how can we bring nagomi into our personal relationships? Our families, our coworkers, and so on?

Mogi: In Japan, the wisdom is to be friends with your enemy. We don’t have a culture of confrontation. Even if we don’t agree with somebody or we don’t like them, the way for nagomi is to keep friendly with them.

If you look at your network structure, it’s a small world, right? Your friend’s-friend’s-friend’s-friend’s-friend’s friend is Barack Obama. You know, the “six degrees of separation.” So if you do business dealings or social activities, eventually you are going to interact with the guy you don’t like or agree with.

The Japanese way of nagomi is to keep a certain degree of friendship. I think that’s one of the key insights into Japanese society. Of course, Japanese people have their own opinions, but the way of nagomi is to not make it into a catastrophic confrontation.

Now, a culture of confrontation could be great in some cases. Occupy Wall Street: I think that was great. But if you look at France, they have street demonstrations at the moment. Israel, too. But in Tokyo, we don’t see that quite as often, especially in recent years. I think that’s probably because the Japanese people try to seek other ways to change society, in an affirmative but more gradual and sustainable manner. It’s a different approach to social reform.

The dangers of a life overly optimized

Kevin: That reminds me of someone you mentioned in your book: [Eiichi] Shibusawa, the father of Japanese capitalism. He had that kind of reform mentality.

Mogi: Yes!

Kevin: Could we discuss him for a bit? I found his ethical and philosophical approach to business interesting.

Mogi: He founded many important companies, but unlike American companies, his concern was not to maximize profit. He was always thinking about society. By the way, rumor has it that he had 130-something children.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Mogi: That may be why his empire didn’t continue to exist, because all his riches were divided by his children. That’s one rumor anyway. [Laughs.]

In a way, Shibusawa’s approach was quite similar to the open-source movement, in the sense of sharing profit among all participants. People don’t talk much about DAOs and Web 3.0 anymore, but I think these things are nagomi and in line with what Shibusawa mentioned. Even today, if you look at Japanese companies, the pay CEOs receive is much less than their American counterparts. The difference between the CEOs and company employees is not so great. That’s the legacy of Shibusawa: to share profit among people.

Kevin: As I read your book, I kept thinking about optimization. We revere making things optimal. Corporations, as you mentioned, are all about optimizing profits. People try to optimize their day. But you seem to suggest that when we optimize one thing, we lose focus of something else, and that other thing could be crucially important, too. What do you think?

Mogi: Spot on. You know, I’m interested in artificial intelligence, too. Maybe you’ve come across this concept of the paper clip maximizer?

Kevin: Can you give me a refresher?

Mogi: It’s a thought experiment by Nick Bostrom, and it’s wonderful. The idea is that there’s an AI designed to maximize the production of paper clips, and the world becomes a place where there are only paper clips. It shows the ridiculous nature of optimization. As you mentioned, if you optimize the system in one respect, that doesn’t necessarily mean the whole thing will get better.

Sometimes, inefficiency can be the result of nagomi. The sub-optimal might be the result of nagomi. That’s something we should keep in mind when looking at many things.

– Ken Mogi

From the perspective of Japan, I think one of the fascinating aspects of the United States is that it’s always concerned with progress, and that’s wonderful. I’m a part of that. But at the same time, that could mean that optimizing in one dimension might not be so beneficial for other aspects of life. Sometimes, inefficiency can be the result of nagomi. The sub-optimal might be the result of nagomi. That’s something we should keep in mind when looking at many things.

Do you have friends who are not focused on success so much as enjoying themselves? I mean, people may look at them and say, “They’re not doing their best; they’re a failure.” But they might actually have established nagomi between work and life.

I have a great friend who has been studying the philosophy of time for many years, but he doesn’t have any university positions, and he’s not very successful. But he’s really fond of eating a good meal. He’s happily married to his wife. He’s not a failure. He’s great. His way of life is just nagomi.

Kevin: I have a friend like that, and I think of him when I’m struggling to find balance. I find I’m at my most stressed and least fulfilled when one area of my life takes control. Meanwhile, he’s walking through life with a permanent smile on his face. [Laughs.]

Mogi: Exactly. I know some people in Japan who are musicians. They haven’t won any Grammys, but they’re enjoying their musical lives very much. Nobody can say that their life is a failure. If you establish your nagomi, I think you can be really happy.

Cultivate nagomi in your life

Kevin: I like that insight into happiness. I’m going to have to ponder that one more.

Final question: What is one thing our readers could do over the weekend to bring a sense of nagomi into their lives?

Mogi: I think whatever you’re doing, do the opposite. [Laughs.] In my case, I work from morning to night, but I go for a run every day. I actually just finished the Tokyo Marathon this March. That’s what I do to establish nagomi; otherwise, I’m glued to the computer.

So, if you’re an indoor person, go outdoors. If you are always driving, go for a walk. If your comfort zone is with your friends and family, find a situation where you have to meet new people. Alternatively, if you are always uneasy and surrounded by strangers, go back to your friends and enjoy some time with them. Going in a diagonal direction from your usual routines would be a dynamic way to establish nagomi. I recommend that.

Kevin: It was great talking with you. Thank you for your time. Where can people find you online if they want to learn more about nagomi, neuroscience, or consciousness?

Mogi: I have my Twitter account (@kenmogi) and also my YouTube channel. Check them out, please.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

* This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.