The future in 1939: Microfilm and Elektro the Moto-Man

Credit: Joseph Binder / Wikimedia Commons

- The New York World’s Fair of 1939-40 showcased microfilm, described by H. G. Wells as “a complete planetary memory for all mankind.”

- The exhibition also featured a message from Einstein to the people of 6939 AD, and a debonair smoking robot.

- The most popular exhibit was Norman Bel Geddes’ Futurama, an 18-minute conveyor belt ride over a diorama imagining America in 1960.

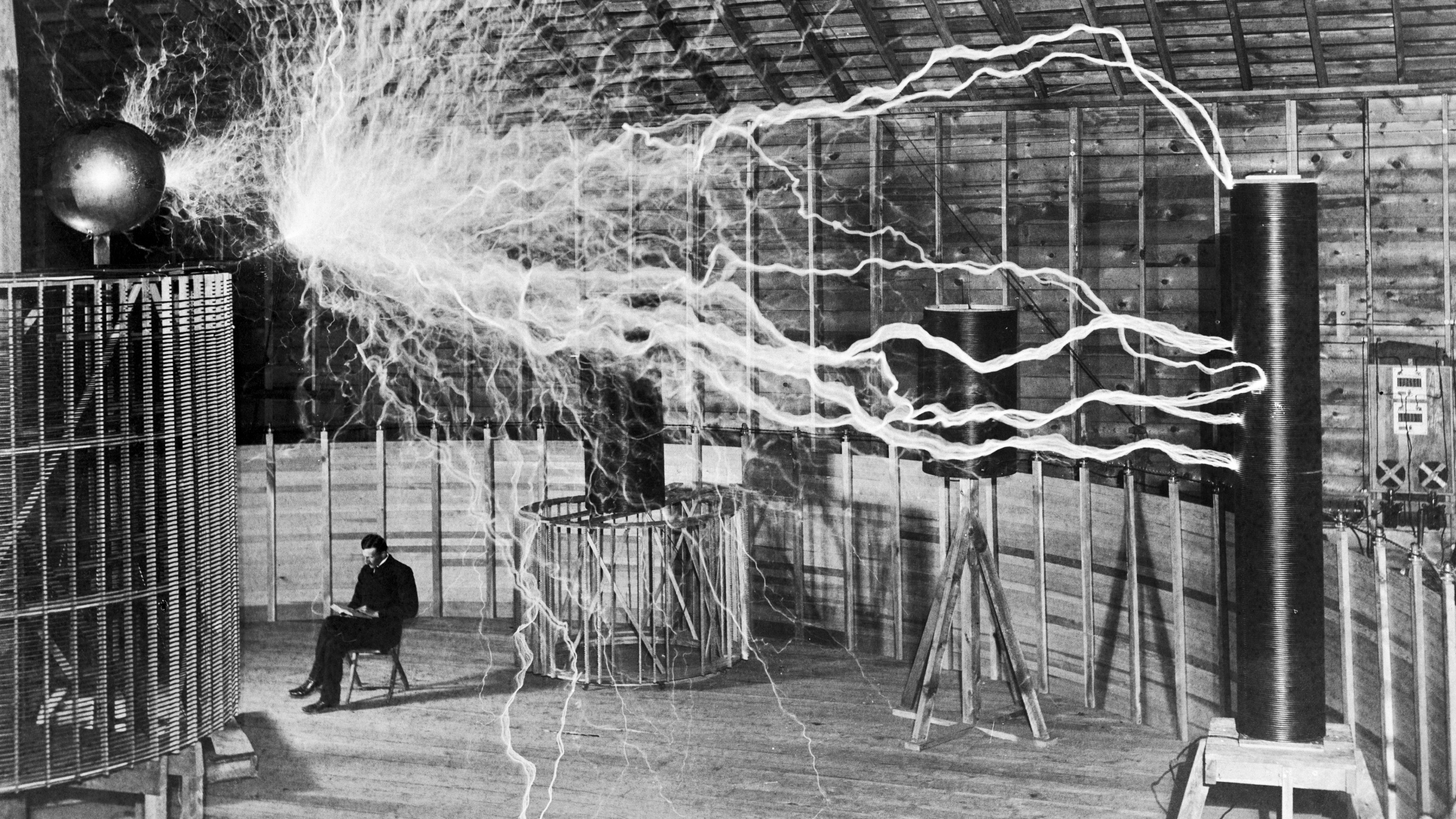

“I trust that posterity will read these statements with a feeling of proud and justified superiority.” This is how Albert Einstein signed off on his brief message to the people of the year 6939 AD, having already related to them that, despite the incredible progress made by people of his own era—“We are crossing the seas by power [and] have learned to fly, and we are able to send messages and news without any difficulty over the entire world through electric waves”—there was also terrible poverty, inequality, and violence, such that “people living in different countries kill each other at irregular time intervals.” Einstein wished the citizens of tomorrow all the best, but on the whole, he considered that “anyone who thinks about the future must live in fear and terror.”

This remarkable statement by the great physicist was occasioned by an equally remarkable exercise in corporate branding: the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Time Capsule, made for the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair. A supremely appropriate choice for an event billed as “the World of Tomorrow,” the time capsule was also an ambitious indexing of the present. Packed inside it was a trove of “objects of common use,” some of them obviously selected with an eye to product placement—a plastic Mickey Mouse cup, Elizabeth Arden cosmetics, and of course, various items manufactured by Westinghouse itself. Plant seeds were put into the capsule, a dollar bill and change, a copy of the Holy Bible.

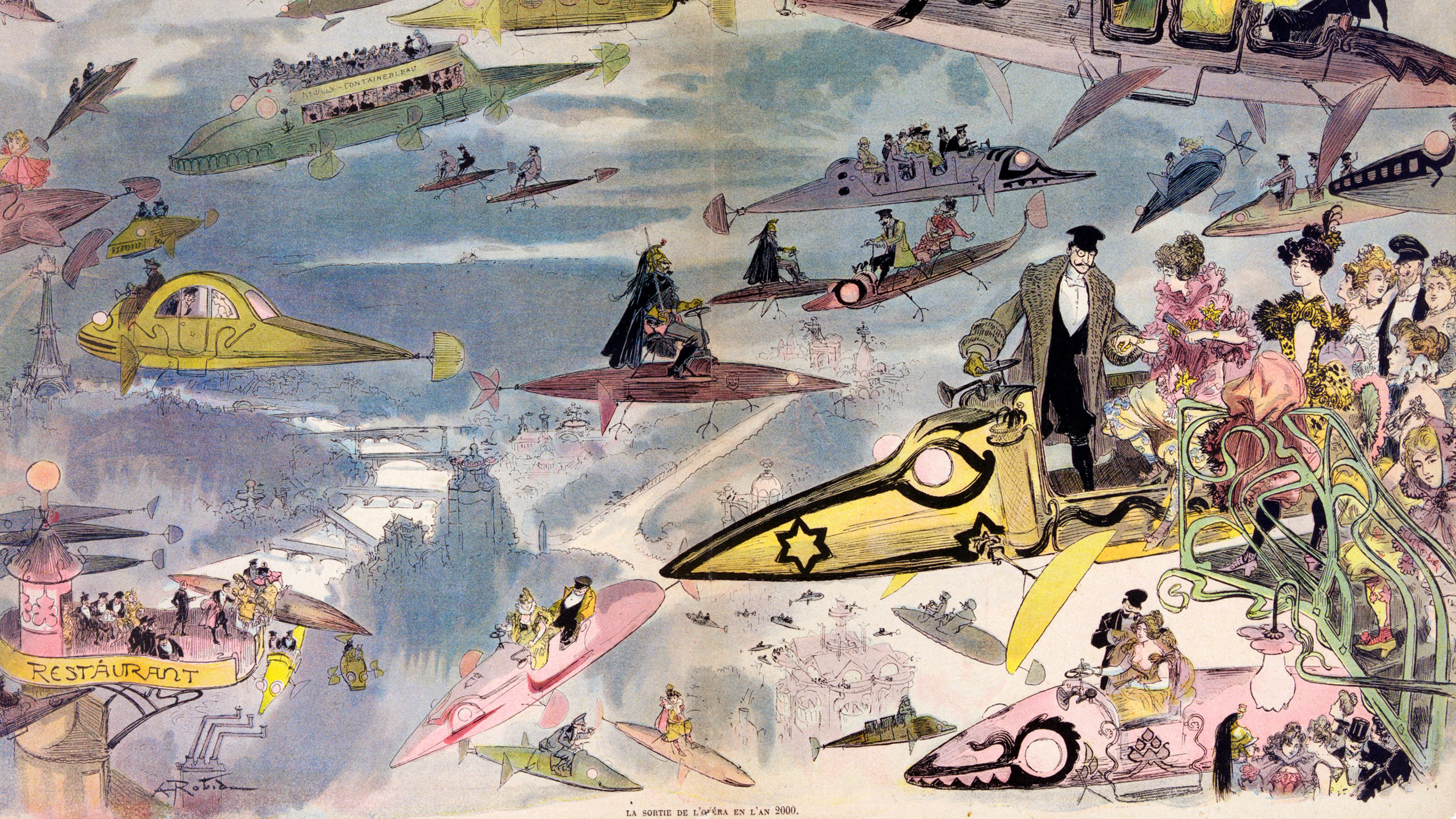

Einstein’s message to the distant future was one of several solicited from “notable men of our time.” One of the others was the German novelist Thomas Mann, who sounded an even more despondent note: “We know now that the idea of the future as a ‘better world’ was a fallacy of the doctrine of progress. . . . In broad outline, you will actually resemble us very much as we resemble those who lived a thousand, or five thousand, years ago. Among you too the spirit will fare badly.” Then there were the documents: a newsreel of significant events—President Roosevelt delivering a speech, Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics, a Soviet rally in Red Square, the Japanese bombing of Canton—and over twenty-two thousand pages of information captured on microfilm, a magical new technology described by H. G. Wells as “a complete planetary memory for all mankind.”

Finally, there was the time capsule itself, a streamlined torpedo to the future, beautifully engineered in a customized, corrosion-resistant copper alloy and buried fifty feet deep at the fairground in September 1938, well in advance of the event’s opening. Lest the time capsule be forgotten, three thousand copies of a Book of Record, “printed on permanent paper with special inks,” were distributed to libraries worldwide, with a list of its contents and its exact location in latitude and longitude. Thinking of everything, the organizers at Westinghouse even put instructions for building a microfilm reader into the capsule, as well as a “Key to the English Language,” in the likely event that five thousand years later, it had fallen entirely out of use.

Like every futurological gesture, the Westinghouse Time Capsule was very much of its own moment: an expression of technocratic confidence shadowed by the return of war. The same was true of the World’s Fair as a whole; it radiated future- facing optimism, with its theme of “The World of Tomorrow” and its dynamic central features, the Trylon and Perisphere, the biggest abstract sculptures anyone had ever seen. But current events could not be ignored. By the time the fair closed in 1940, several of the countries that had participated no longer existed; they had been invaded and occupied. The Soviet Pavilion, meanwhile, was dominated by a 188-foot-tall tower topped with an unnerving stainless steel sculpture of an anonymous worker, which the American press nicknamed “Big Joe.” The Soviets’ message: the future had arrived, and it was them.

The Soviets’ message: the future had arrived, and it was them.

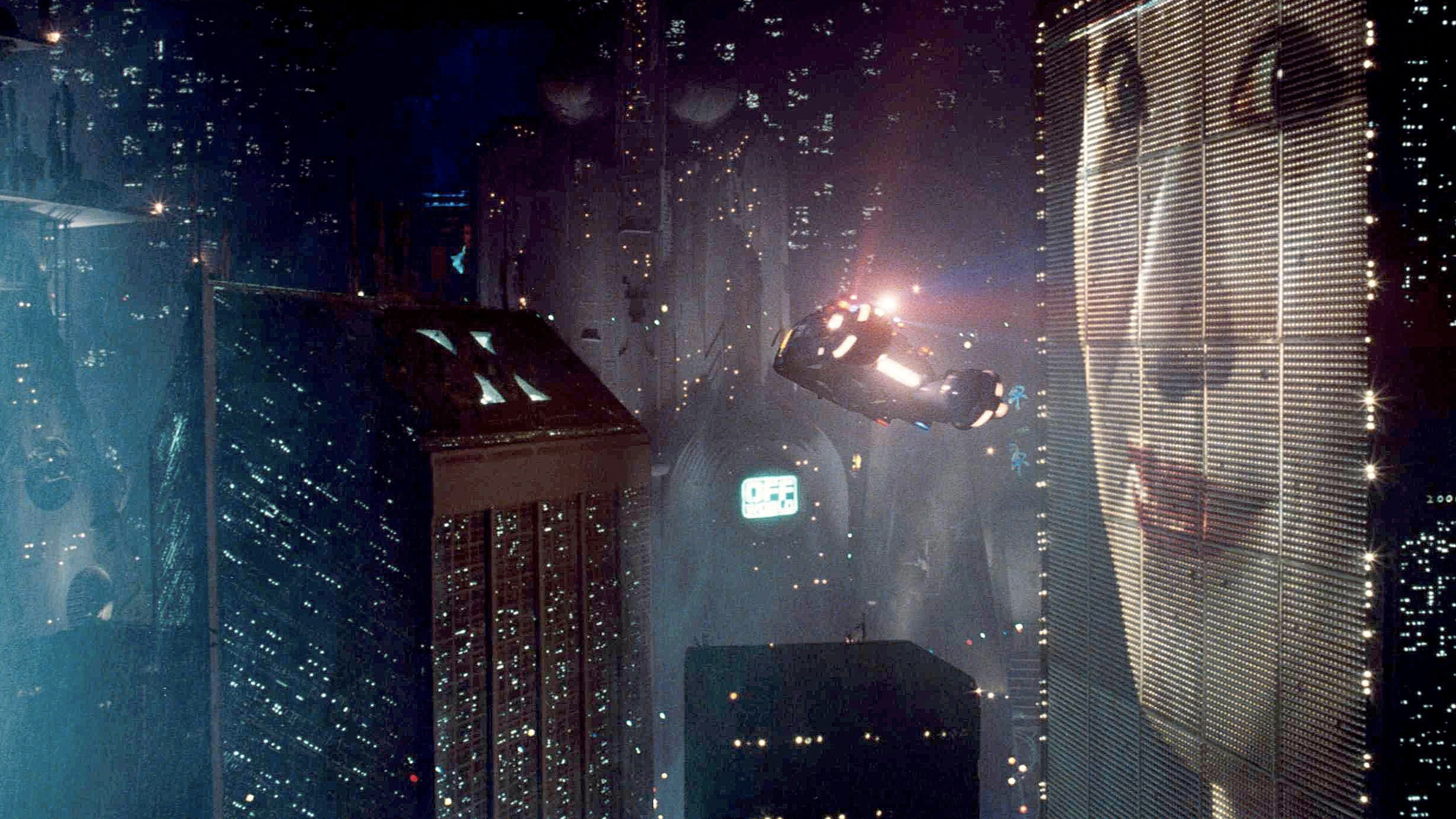

As for the Americans—they had Norman Bel Geddes. His General Motors Futurama was the hands-down favorite of fairgoers, reportedly seen by about half of all visitors, more than twenty-four million people. He was not the only industrial designer to contribute. Raymond Loewy, commissioned by Chrysler, imagined a sci-fi launchpad for interstellar rocket travel. Henry Dreyfuss produced Democracity, a model of a utopian future metropolis contained inside the Perisphere. Walter Dorwin Teague, the solid citizen of the design scene, was entrusted with no fewer than seven corporate pavilions. The most ambitious of these, for the Ford Motor Company, included “The Road of Tomorrow,” with red, yellow, and blue cars constantly circling a half-mile track.

There were also novel machines throughout the fair. It was the first time that the general public ever experienced air-conditioning (presented in the “Carrier Igloo of Tomorrow”), fax machines, and broadcast television, as well as new industrial products like nylon and Formica. Westinghouse, in addition to its time capsule, presented a robot similar to William H. Richards’s R.U.R.-inspired Eric, named Elektro the Moto-Man; seven feet tall, it smoked cigarettes and spoke set phrases to visitors, such as “My brain is bigger than yours.” The Borden Dairy Company had a hit with their “Spokes-cow” Elsie. She was flesh and blood, but welcomed visitors to the “dairy world of tomorrow,” featuring a huge revolving platform called the Rotolactor where cows were mechanically milked, with integrated equipment for pasteurization, irradiation, bottling, and capping—quite an improvement on the cream separator in Eisenstein’s The Old and the New.

The Futurama was a marvel in its own right, both in its scale—thirty-five thousand square feet and a third of a mile long—and its detail.

Nothing, though, could match Bel Geddes’ Futurama. Visitors to the attraction were treated to an eighteen-minute ride seated on a conveyor belt, which took them on an effortless flight path over a diorama showing America in 1960. Life magazine observed that this imagined future seemed to be “full of a tanned and vigorous people, who in twenty years have learned to have fun,” then more seriously added that it demonstrated “what Americans, with their magnificent resources of men, money, materials and skills, can make of their country by 1960, if they will.” This aspirational note was sounded throughout, as spectators soared over one futuristic wonder after another: experimental farms, clusters of skyscrapers, private aircraft on rooftop landing pads, and most importantly from General Motors’ point of view, multilane highways crowded with cars, cars, and more cars, some of them remote-controlled from towers, to aid in traffic flow.

The Futurama was a marvel in its own right, both in its scale—thirty-five thousand square feet and a third of a mile long—and its detail. Every feature was hand-made: rivers of polished steel, roads made of rubber, hills built up in plaster and variously covered with velour or crushed cornflakes. Bel Geddes drew on his theater experience to devise a scheme of five hundred concealed floodlights to simulate the sun’s passage from afternoon to dusk to dawn. Thus the exhibit was both a topographical map, based on specially commissioned aerial photography, and a clock, which immersed the visitor into its own time. At the end of the ride, visitors disembarked into a full-size futuristic mock-up of a traffic intersection, which also served as a viewing platform over a display of the latest GM automobile models. Finally, each person was handed a badge, reading: “I have seen the future.”