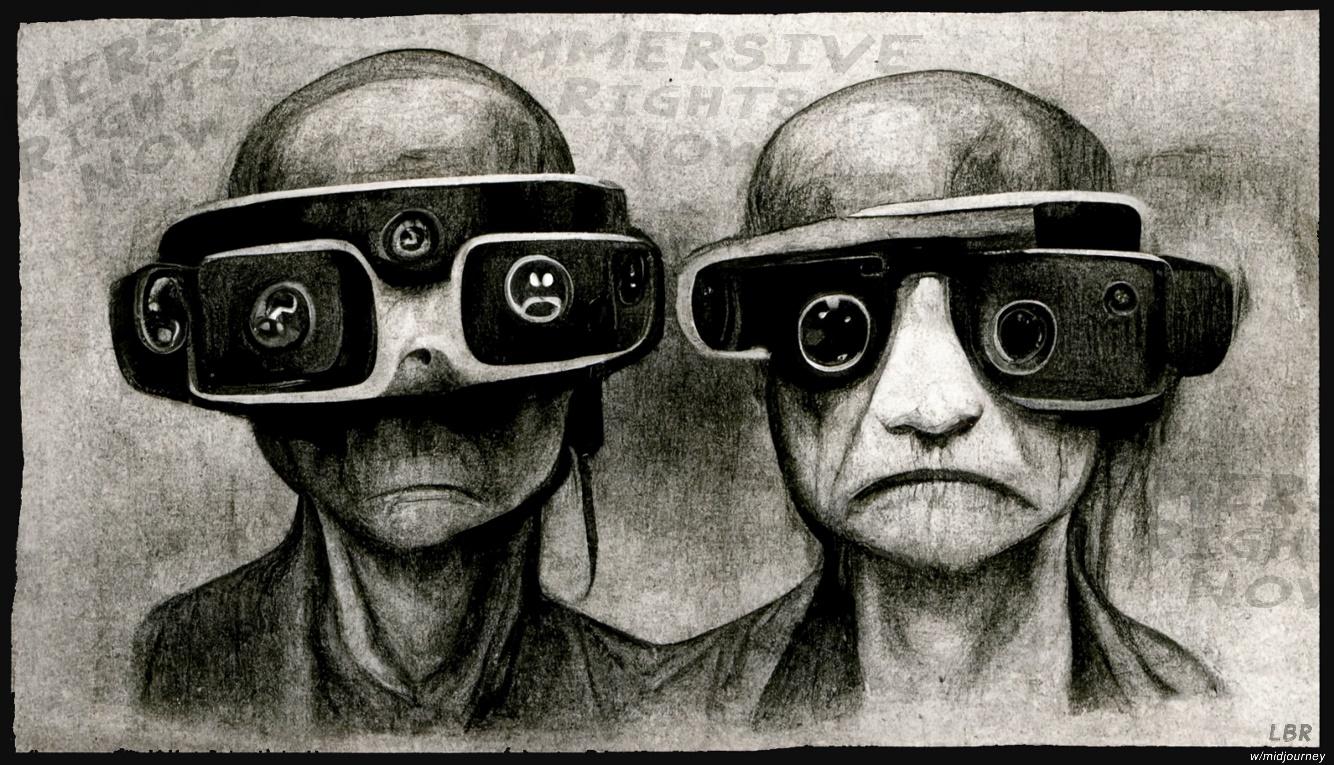

“Playing God”: How the metaverse will challenge our very notion of free will

- The metaverse will revolutionize the world, in both good and bad ways.

- One particularly concerning use of the metaverse will be the ability of third parties to monitor your expressions and vital signs, adjusting their interactions with you in real-time to optimize impact. This could occur for benign reasons, like selling you a car, or nefarious ones, like trying to convince you to accept disinformation.

- In this way, advanced technology inside the metaverse will challenge our very notion of free will.

The United Nations Human Rights Council recently adopted a draft resolution entitled Neurotechnology and Human Rights. It’s aimed at protecting humanity from devices that can “record, interfere with, or modify brain activity.” To describe the risks, the resolution uses euphemistic phrases like cognitive engineering, mental privacy, and cognitive liberty, but what we’re really talking about is mind control.

I applaud the UN for taking up the issue of mind control, but neurotechnology is not our greatest threat on this front. That’s because it involves sophisticated hardware ranging from “brain implants” to wearable devices that can detect and transmit signals through the skull. Yes, these technologies could be very dangerous, but they’re unlikely to be deployed at scale anytime soon. In addition, individuals who submit themselves to implants or brain stimulation will likely do so with informed consent.

On the other hand, there is an emerging category of products and technologies that could threaten our cognitive liberties across large populations, requiring nothing more than consumer-grade hardware and software from trusted corporations. These seemingly innocent systems, which will be marketed for a wide range of positive applications from entertainment to education, targeting both kids and adults, could be dangerously misused and abused without our knowledge or consent.

I’m talking about the metaverse. To explain why, I would first like to introduce an engineering concept that helps me think objectively about the potential dangers of interactive systems. The concept is feedback control, and it comes from a technical discipline called control theory.

Control systems

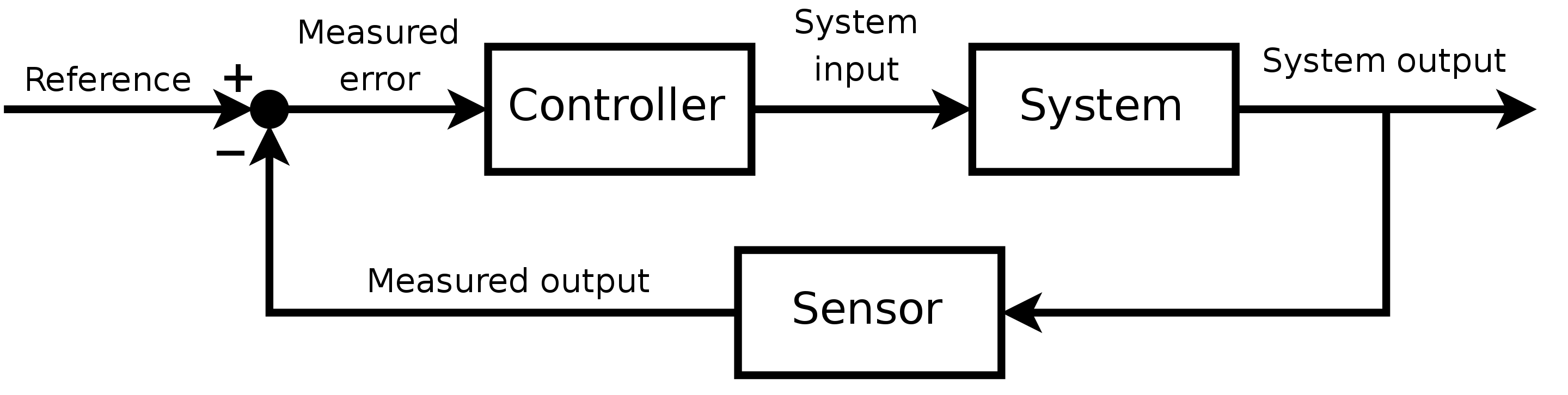

Control theory is merely the name given by engineers and scientists to the formal method used for influencing the behaviors of a system. That system could be anything that interacts with the world. Think of a cheap nightlight with a sensor on it. When it gets dark outside, the nightlight comes on. When it gets light out again, the nightlight goes off. That’s a control system.

Now, consider a slightly more complex example: the thermostat in your house. Unlike a nightlight with only two states (“on” or “off”), your house can be a range of temperatures. You set a goal and if your house falls below that goal, your heat turns on. If your house gets too hot, it turns off. When working properly, your thermostat keeps your house close to the goal you set. That’s feedback control. This simple concept is generally represented in a standard format called a control system diagram.

The diagram has three key boxes labeled system, sensor, and controller. In the heating example, your house would be the system, a thermometer would be the sensor, and the thermostat would be the controller. An input signal called the reference is the temperature you set as the goal. The goal is compared to the actual temperature in your house (that is, measured output). The difference between the goal and measured temperature is fed into the thermostat which determines what the house’s heater should do. If the house is too cold, its heater turns on. If it’s too hot, its heater turns off.

Of course, control systems can get sophisticated, enabling airplanes to fly on autopilot, cars to autonomously navigate traffic, and robotic rovers to land on Mars.

In the metaverse, you are the system being controlled

With that background, let’s jump back into the metaverse, which is largely about transforming how we humans interact with the digital world. In today’s society, we mostly consume “flat media” viewed from the third-person perspective. In the metaverse, digital content will become immersive experiences that are spatially presented all around us. This shift to first-person interactions fundamentally will alter our relationship with digital information, changing us from outsiders peering in at content to active participants engaging with content presented naturally in our surroundings. In other words, we will literally climb into and become part of the information system.

Before I describe the risks of immersive technologies, I need to express that the metaverse has the potential to be a deeply humanizing technology. After all, it will provide us with information in the format our senses were meant to perceive it — as natural first-person experiences, not as flat documents viewed through little windows. I truly believe this will be a major benefit for humanity. Thirty years ago, I described the potential like this: “Given the ability to draw upon our highly evolved human facilities, users of virtual environment systems can obtain an intimate level of insight and understanding.”

I still believe this, but the power of immersive media can work in both directions. Used in positive ways, it can unlock insight and understanding for people around the globe. Used in negative ways, it could unleash the most powerful tool of persuasion and manipulation we have ever created. That’s because immersive media can be far more impactful than traditional media, targeting our perceptual channels in the most personal and visceral form possible: as experiences.And because we humans evolved to trust our senses (that is, to believe our eyes and ears), the very notion that we can see, hear, and feel things directly around us that are entirely fabricated is not a situation that we are mentally prepared for.

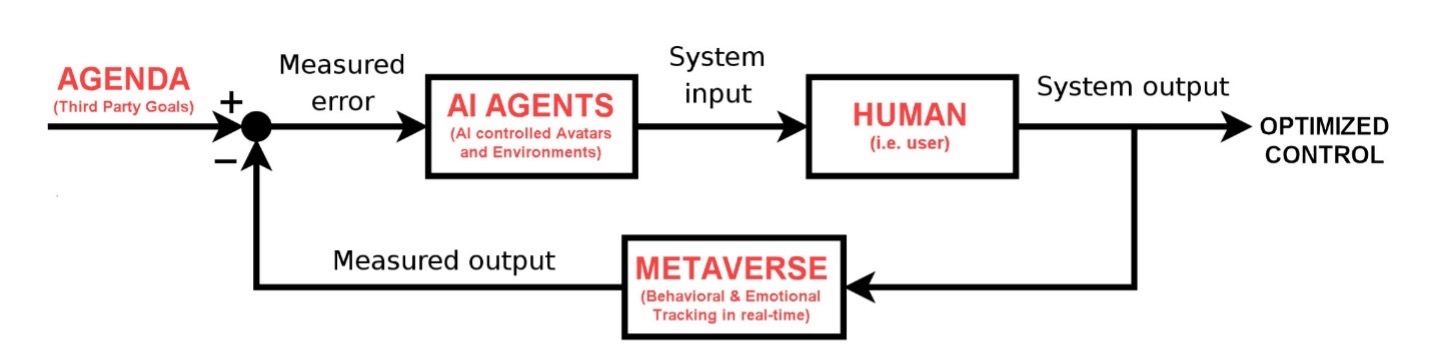

But that’s not the most dangerous aspect of the metaverse. To appreciate the true danger of immersive technologies, we can use the basics of control theory. Referring back to the diagram above, we see that only a few elements are needed to effectively control a system, whether it’s a simple nightlight or a sophisticated robot. The two most important elements are a sensor to detect the system’s real-time behaviors and a controller that can influence those behaviors. The only other elements needed are the feedback loops that continually detect behaviors and impart influences, guiding the system toward desired goals.

Inside the metaverse, the system being controlled is you. When you put on a headset and sink into the metaverse, you are immersing yourself into an environment that has the potential to act upon you more than you act upon it. That means that you are the system most likely to be controlled — an inhabitant of a fabricated world that can monitor and influence you in real-time.

When seen in this light, the system input includes the immersive sights, sounds, and touch sensations that are fed into your eyes, ears, hands, and body. This is overwhelming input — possibly the most extensive and intimate input we could imagine. This means the ability to influence the system (you) is equally extensive and intimate. On the other side of the human user is the system output — in other words, your real-time actions, reactions, and interactions. This includes everything your body does that potentially could be tracked by sensors.

Sensational sensors

In the metaverse, sensors will track everything you do in real-time, such as the subtle motions of your head, hands, and body. That includes the direction you are looking, how long your gaze lingers, the faint motion of your eyes, the dilation of your pupils, and the changes in your posture and gait. Even your vital signs, like heart rate, respiration rate, and blood pressure, are likely to be tracked in the metaverse.

For example, the most recent headset deployed by Meta can accurately track your eye movement and facial expressions, including expressions that we make subconsciously that are too fast or subtle for human observers to recognize. Known as “micro-expressions,” they can convey emotions that users had not intended to express and are unaware of revealing. Users may not even be aware of feeling the emotions, leading to situations where the system literally knows the user better than they know themself.

Furthermore, AI can infer information that is not directly detected by sensors. In a recent paper, researchers at Meta showed that when processing “sparse data” from just a few sensors on your head and hands, AI technology could accurately predict the position, posture, and motion of the rest of your body. Other researchers have shown that body motions such as gait can be used to infer a range of medical conditions from depression to dementia.

Additionally, technology already exists to infer your emotions in real-time from your facial expressions, vocal inflections, gestures, and body posture. Other technologies exist to detect emotions from the blood-flow patterns on your face and the vital signs detected from sensors in your earbuds. This means when you immerse yourself into the metaverse, almost everything you do and say will be observed, and then that data will be used to predict how you feel during each action, reaction, and interaction.

Of course, this information will be recorded and used again. With this data, AI could create behavioral and emotional models to predict how you would react to a wide range of stimuli. And because the metaverse is not just virtual reality but also augmented reality, the tracking and profiling of users could occur throughout our daily lives, from the moment we wake up to the moment we go to sleep.

The ultimate influencer

This takes us one giant step toward mind control, potentially making the metaverse the most dangerous tool of persuasion ever created. To appreciate the risks, we need to consider the final box in the system, the controller.

The controller could be software running on processors that make extensive use of AI technology. The controller receives a measured error, which is the difference between a reference goal (a desired behavior) and the measured output (a sensed behavior). To bring this back to the topic of mind control, the goal could be the agenda of a third party that aims to impart influence over a user. (See diagram below.) That third party could be a paying sponsor that desires to persuade a user to buy a product, subscribe to a service, or even believe some propaganda, ideology, or misinformation.

Of course, advertising and propaganda already exist with traditional marketing techniques. What is unique about the metaverse is the ability to create high-speed feedback loops in which a user’s behaviors and emotions are continuously fed into a controller that adjusts its influence in real-time for optimized persuasion. This process could easily cross the line from marketing to mind control.

At its core, a controller aims to “reduce the error” between the desired behavior of a system and the measured behavior of the system. In the metaverse, a controller would modify the virtual or augmented environment the user is immersed within. In other words, the controller can alter the world around the user, modifying what that user sees and hears and feels in order to drive the user toward the desired goal. And because the controller can accurately monitor how the user reacts to its alterations of the world, it will be able to adjust in real-time, optimizing the persuasive impact in much the same way that a thermostat optimizes the temperature of a house.

Mind control scenarios in the metaverse

Imagine a user sitting in a coffee house (virtual or augmented) in the metaverse. A third-party sponsor wants to inspire the user to buy a particular product, say a new car. In the metaverse, advertising will not be the pop-up ads and videos that we’re familiar with today but will be immersive experiences that are seamlessly integrated into our surroundings. So, the controller might create a virtual couple sitting at the next table. That virtual couple will be the system input used to influence the user.

The controller will design the virtual couple for maximum impact. This means the age, gender, ethnicity, clothing style, speaking style, mannerism, and other qualities of the couple will be selected by AI algorithms to be optimally persuasive to the target user based on that user’s historical profile. Next, the couple will engage in an AI-controlled conversation among themselves that is within earshot of the target user — that new car they bought is just awesome!

As the conversation begins, the controller monitors the user in real-time, assessing micro-expressions, body language, eye motions, pupil dilation, and blood pressure to detect when the user begins paying attention. This could be as simple as detecting a subtle physiological change in the user correlated with comments made by the virtual couple. Once engaged, the controller will modify the conversational elements to increase engagement. For example, if the user’s attention increases as the couple talks about the car’s horsepower, the conversation will adapt in real-time to focus on performance.

As the overheard conversation continues, the user may be unaware that they have become a silent participant, responding through subconscious micro-expressions, body posture, and changes in vital signs. The AI-driven controller will highlight elements of the new car that the target user responds most positively to and provide conversational counterarguments when the user’s reactions are negative. And because the target user does not overtly express objections, the counterarguments could be profoundly influential. After all, the virtual couple could verbally address emerging concerns before those concerns even have fully surfaced in the mind of the target user. This is not marketing; it’s mind control.

In an unregulated metaverse, the target user may believe the virtual couple are avatars controlled by other patrons. In other words, the target user easily could believe that they are overhearing an authentic conversation among users rather than a promotionally altered experience that was targeted specifically at them. A more aggressive controller could engage the user directly. An AI-controlled avatar pushing an agenda-driven promotional conversation could fool users into thinking they are interacting with other human beings.

Of course, selling a car is a relatively benign example. Far more concerningly are third-party agendas whose aims are more nefarious, such as influencing target users to accept some political ideology, extremist propaganda, or disinformation.

“Playing God”

AI systems can outplay the world’s best human competitors at chess, go, poker, and other strategy games. So, what chance does an average consumer have when engaged in promotional conversation with an AI agent that has access to that user’s personal background and interests, and can adapt its conversational tactics in real-time based on subtle changes in pupil dilation and blood pressure? The potential for violating a user’s cognitive liberty through this type of feedback control in the metaverse is substantial.

In fact, it could be the closest thing to “playing God” that any mainstream technology has ever achieved. That’s a bold statement, and I don’t make it lightly. I have been in this field for over 30 years, performing research at Stanford, NASA, and the U.S. Air Force, after which I founded a number of successful companies in this space. I genuinely believe the metaverse can be a positive technology for humanity, but if we don’t protect against the downsides by crafting thoughtful regulation, it could challenge our most sacred personal freedoms — including our basic capacity for free will.