The Fragmentation of Bretton Woods

LAGUNA BEACH – The world has changed considerably since political leaders from the 44 Allied countries met in 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to create the institutional framework for the post-World War II economic and monetary order. What has not changed in the last 70 years is the need for strong multilateral institutions. Yet national political support for the Bretton Woods institutions – the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank – seems to have reached an all-time low, undermining the global economy’s ability to meet its potential and contributing to geopolitical insecurity.

When the Bretton Woods conference was convened, its participants understood that the IMF and the World Bank were integral to global stability. Indeed, both institutions were designed to discourage individual countries from adopting short-sighted policies that would harm other economies’ performance, incite retaliatory action, and ultimately damage the entire world economy. In other words, they were intended to prevent the kind of beggar-thy-neighbor policies that many major economies adopted during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Moreover, by encouraging better policy coordination and the pooling of financial resources, the Bretton Woods institutions boosted the effectiveness of international cooperation. And they enhanced stability by offering collective insurance to countries facing temporary hardship or struggling to meet their development-financing needs.

It is difficult to identify more than a small handful of countries that have not benefited in some way from the IMF or the World Bank. Yet countries seem hesitant to contribute to the reform and strengthening of these institutions. In fact, a growing number of systemically important countries have taken measures that are undermining the Fund and the Bank, albeit largely inadvertently.

In recent years, mounting domestic political pressure has driven Western governments to adopt increasingly insular policies. And, just a few weeks ago, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) acted to bolster a currency-reserve pool to help ease short-term liquidity pressures and to establish their own development bank – a direct challenge to the IMF and the World Bank.

Indeed, unlike existing parallel arrangements, which have always been regional in nature and intended to complement the work of the IMF and the World Bank, the BRICS’ New Development Bank and contingent reserve agreement are not based on cultural, geographical, or historical links. Instead, they are founded on a shared frustration with the outmoded entitlements to which the US and Europe are clinging – entitlements that are diminishing the Bretton Woods institutions’ credibility and effectiveness.

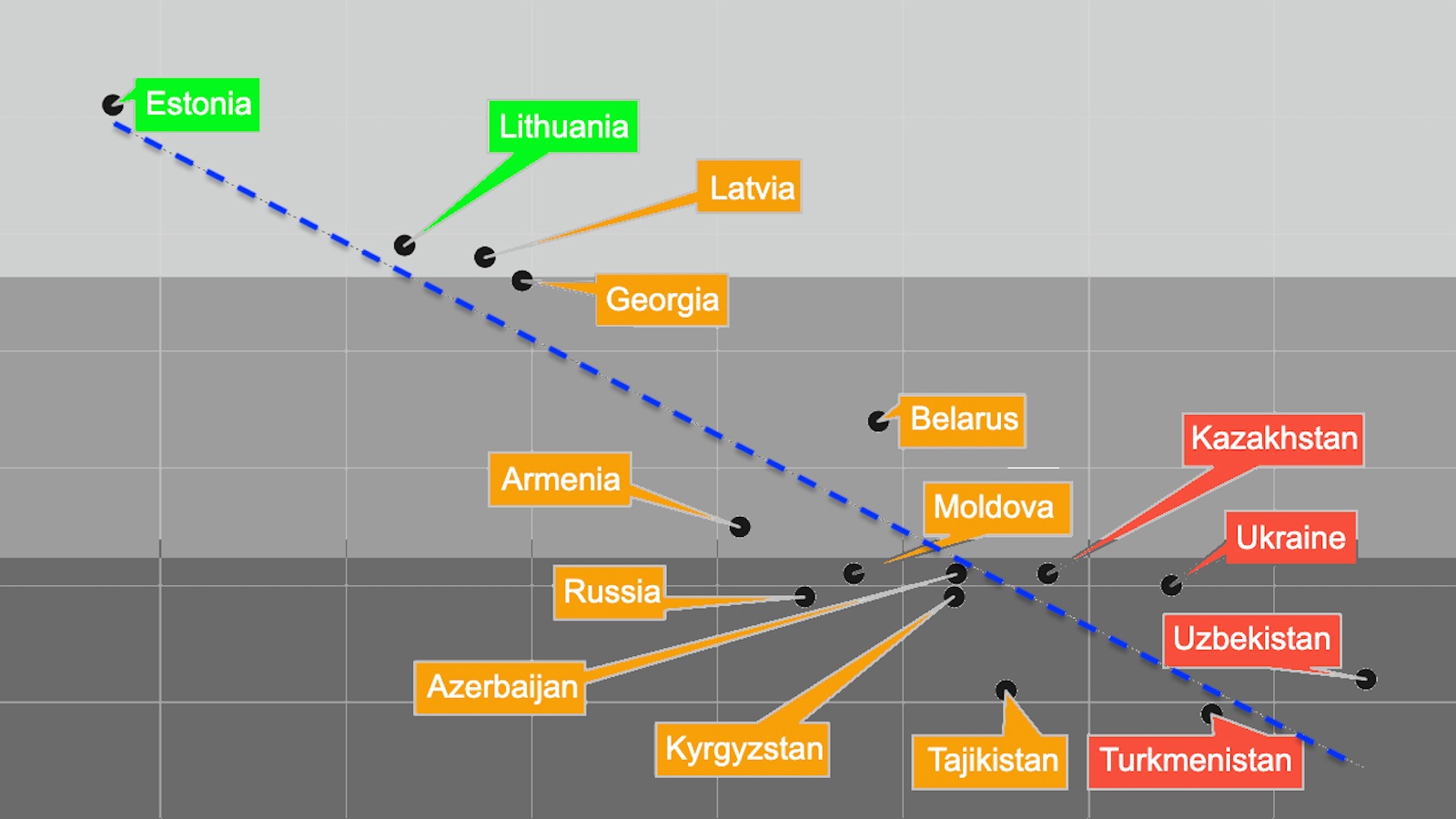

Most important, Europe and the US continue to resist the full dismantling of a nationality-based appointment system that favors their citizens for the highest leadership positions at the IMF and the World Bank, despite offering the occasional promise of change. Moreover, they have stifled efforts to recalibrate the balance of representation even marginally. As a result, Western Europe enjoys a massively disproportionate level of representation, and emerging economies, despite their increasing systemic importance, barely have a voice. And, during the eurozone’s debt crisis, European leaders showed little hesitation in bullying the IMF into flouting its own lending rules.

In this sense, it is the countries that spearheaded the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions that pose the greatest threat to their legitimacy, impact, and, ultimately, relevance. After all, emerging economies cannot reasonably be expected to support institutions that offer unfair advantages to countries that so often preach the importance of meritocracy, competition, and transparency. That is why they are now determined to use their collective economic weight to circumvent these institutions.

Another challenge to the international monetary system lies in the proliferation of bilateral payment agreements. By bypassing more efficient and inclusive structures, these arrangements undermine multilateralism. In some cases, they even conflict with countries’ obligations under the Bretton Woods Articles of Agreement.

The consequences of this gradual process of fragmentation extend well beyond lost economic and financial opportunities, to include weaker political cooperation, reduced interdependencies, and, in turn, growing geopolitical risks. One need look no further than the current turmoil in Ukraine or Iraq to understand what can happen in the absence of credible multilateral structures capable of shaping developments in crisis situations.

So much for the problems. What about the solutions? Simply put, the IMF and the World Bank urgently need self-reinforcing reforms.

With a few key measures – none of which is technically complicated – the Bretton Woods institutions can move beyond the mindset of 1944 to reflect today’s realities and enhance tomorrow’s opportunities. Such reforms include the elimination of nationality-based hiring; adjustments to representation, with emerging economies gaining more influence at the expense of Europe; and more equality and evenhandedness in lending and economic-surveillance decisions.

The challenge will be to overcome political resistance – no small feat at a time when domestic polarization has made politicians wary of publicly supporting economic multilateralism. The repeated rejection by the US Congress of a much more limited set of reforms – which was approved by most other countries in 2010-12, imposes no incremental financial obligations on the US, and implies no reduction in America’s voting power or influence – is a case in point.

Enlightened self-interest must overcome such political obstacles. The longer that world leaders resist the overwhelming need for reform, the worse the world’s future economic and financial prospects – not to mention its security situation – will be.

Mohamed A. El-Erian is Chief Economic Adviser at Allianz and a member of its International Executive Committee. He is Chairman of President Barack Obama’s Global Development Council and the author, most recently, of When Markets Collide.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2014.

www.project-syndicate.org