Let’s not confuse entanglement with teleportation

Image source: Dmitriy Rybin/AnyaPL/Shutterstock/Big Think

- Quantum teleportation and “traditional” teleportation are two very different things.

- The quantum variety involves entanglement; the other kind is even more problematic.

- Recent successes in quantum teleportation may lead to more secure communication in the future.

Quantum entanglement is absolutely mind-bending. Surprising and weird as it is, it’s a genuinely fascinating phenomenon, requiring zero hype to keep us interested. Recent headlines, though — and some physicists on talk shows — have been conflating “quantum teleportation” with good-old sci-fi “teleportation.” It’s not hard to jump to the incorrect conclusion that progress is being made on the latter and not the former. Alas, it’s not so — there’s still no tech on the horizon for beaming ourselves anywhere. Which is not to say that quantum teleportation is not amazing in its own right.

Image source: Natali art collections/Shutterstock

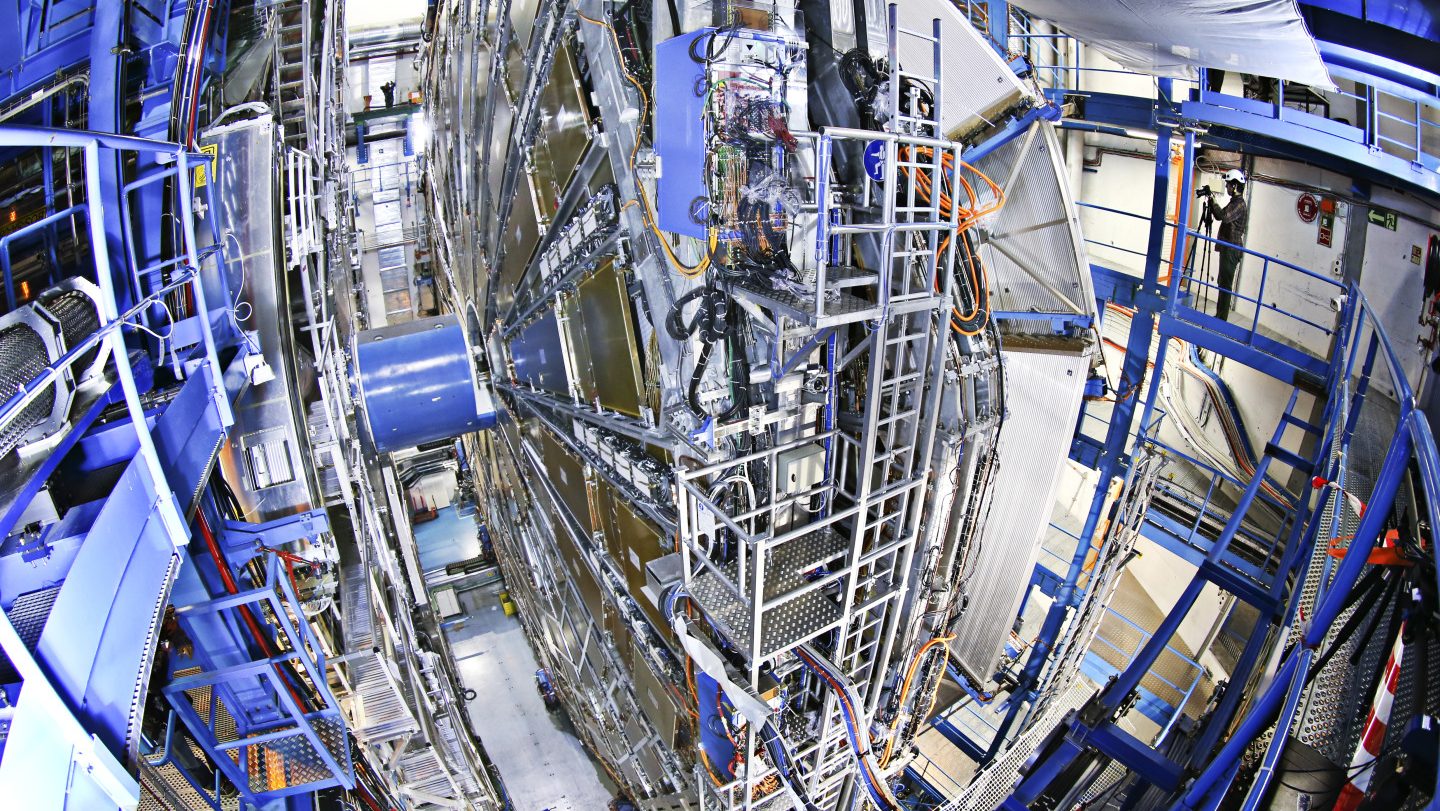

Quantum teleportation

When quantum teleportation was first proposed by physicists Asher Peres and William Wootters in 1993, it was called “telepheresis,” an arguably less-misleading appellation. The term “quantum teleportation” was coined by Peres’ and Wootters’ co-author Charles Bennett. This may be because it looks a lot like standard teleportation, even though it’s not.

Quantum teleportation involves the measurement of the state of one entangled particle and the transfer of that state to an entangled partner, which then assumes that state. One of entanglement’s oddities, as noted by Werner Heisenberg, is that the act of observing the state of a particle alters that state — what’s been observed thus no longer exists. “This situation,” writes Phillip Ball in Nature, “can’t be meaningfully distinguished from one in which the original particle itself has been moved to the target location: that transport has not really happened, but to all appearances it might as well have.”

Quantum communication

Quantum-entangled particles have intriguing potential for the development of extremely secure communication networks. Currently, encrypted data is transmitted as electrical or optical pulses representing ones or zeroes, along with digital keys with which the encryption can be decoded. Hackers are getting better and better at cracking these keys, often without the communicating parties’ knowledge.

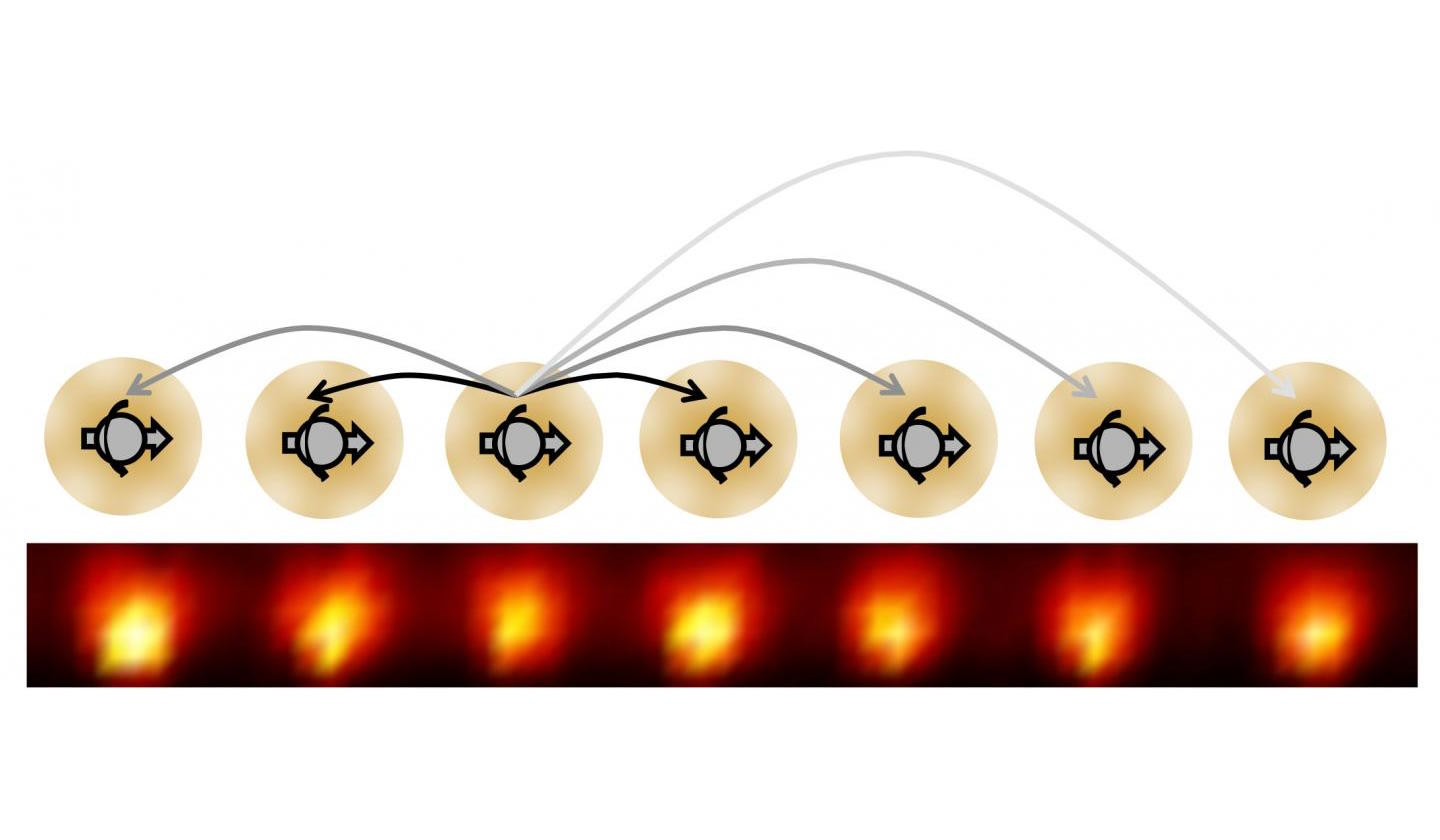

Quantum communication offers a more secure means of sharing important data between parties. Encryption keys comprised of entangled quantum particle pairs can be transmitted to both parties from a satellite as photon “qubits” in super-position, potential combinations of ones and zeros that don’t collapse into their final states until they’re observed. In this “quantum key distribution,” or QKD, the particles should arrive at their destination in their uncollapsed qubit state — when their states are observed, they should be identical. If they’re not, Heisenberg’s principle makes it immediately obvious that the keys have been intercepted and that the communication network is not secure.

There are wrinkles to work out in the the transmission of such particles, including achieving greater distances and maintaining the integrity of transmitted particles. As a result, researchers are focusing on transmissions to and from space, where there’s less in the way to interfere with the entangled particles.

Though the earliest attempts to deliver particles topped out at about 100 kilometers, in 2017, Chinese researchers were able to transmit single photon qubits from a Tibetan-plateau ground station to their Micius satellite orbiting the Earth 1,400 km away. It took millions of attempts, but 911 photons made it up there still identical to their entangled partners back on the ground. That same year, in partnership with Austrian scientists, the team was able to successfully distribute intact qubit quantum keys from Micius to two ground stations in China, and one in Europe, near Vienna.

The latest developments have to do with extending the complexity of quantum teleportation via the development of “qutrits.” Where a qubit can collapse into a zero or a one, a qutrit can be a zero, one, or a two, thus radically expanding the complexity of information it can carry. Two teams have announced successfully creating them, albeit in different ways.

Good, old-fashioned teleportation

When Star Trek first brought teleportation into the popular lexicon in the 1960s, it wasn’t too clear what it actually was There were two main possibilities. Teleportation could be:

- the disassembly of an object’s — or person’s — molecules and atoms for instant transmission to somewhere else and reassembly.

- the transmission of a description of a traveler that would allow their reconstruction in a new location using atoms and molecules found there. This technology, it’s worth noting, would carry with it a grisly bit of cleanup: The original object or person would have to be destroyed at the start of teleportation to avoid the existence of duplicates. Absent this, you’re veering into Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse territory. Really, it’s like making a photocopy and tearing up the original.

As for Star Trek, a teleportation-phobic Star Trek: The Next Generation character finally settled the debate by describing the mode of transportation in colorful detail as being blown apart in one place and put back together in another. Still, you’re right to be creeped out by all the philosophical implications.