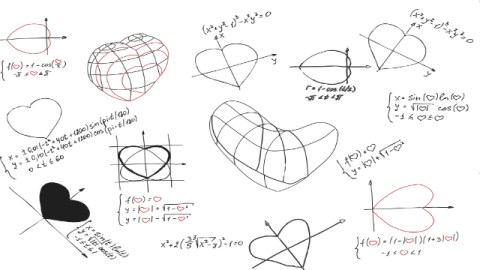

The Mathematics of Happiness?

What’s the Big Idea?

An iPad can calculate faster than the human brain, but in the areas of creativity and abstract thought, even massive supercomputers lag far behind the average human three year old. Still, the size of our computer databases and their processing power is increasing so rapidly that data and algorithms for interpreting it are becoming formidable sources of political and economic power. In education, finance, and government, it seems, he who has the most inscrutable machines and impressive statistics sets the agenda.

The trouble with this is that the qualitative data about our lives – the quality of our relationships, the happiness of our children, our level of satisfaction at work – is often left out of the equation (and therefore the agenda) because it’s much more difficult to measure.

Chip Conley, Founder of Joie De VivreHospitality and the author of Emotional Equations, argues (against Einstein, as it happens), that everything that counts can and ought to be counted. A hotelier by trade, he says that GDP and the bottom line are blunt instruments for measuring the health of a society or a business. After the dot.com crash of 2001, and a visit to the Buddhist nation of Bhutan, which has a “Gross National Happiness” index, Conley and his team decided to create indices for measuring the well-being of their employees and customers.

These initiatives, he says, led to significant increases in customer loyalty to Joie de Vivre hotels and a turnover rate well below the industry standard, not to mention bottom-line success at a terrible time for the hospitality industry.

In Emotional Equations, Conley takes the mathematics of human happiness a step further, creating simple formulas like anxiety = uncertainty x powerlessness, which, when used systematically, he says, can give individuals and organizations a concrete method for addressing the human needs that drive them.

What’s the Significance?

Whether or not you’re convinced by the idea of emotional mathematics, Conley is making two important points here. First that in a global economy that is 64% service-driven, businesses can’t afford to ignore the needs of the human beings that work for them. Sorry, McDonalds, but the “free meal if your cashier doesn’t smile” improves my day only if my server doesn’t smile and I get the free meal, and improves my server’s day, never.

Second, that in our data-is-power world, any hope we might have of a reasonably humane future in which cooperation and decency are incentivized may depend on our ability to represent our higher human needs mathematically, and to build these representations into the increasingly arcane systems that drive education, politics, and the economy.

Follow Jason Gots (@jgots) on Twitter

Image credit:Shutterstock.com