running

A new study compared cognitive boosts from running versus relaxing.

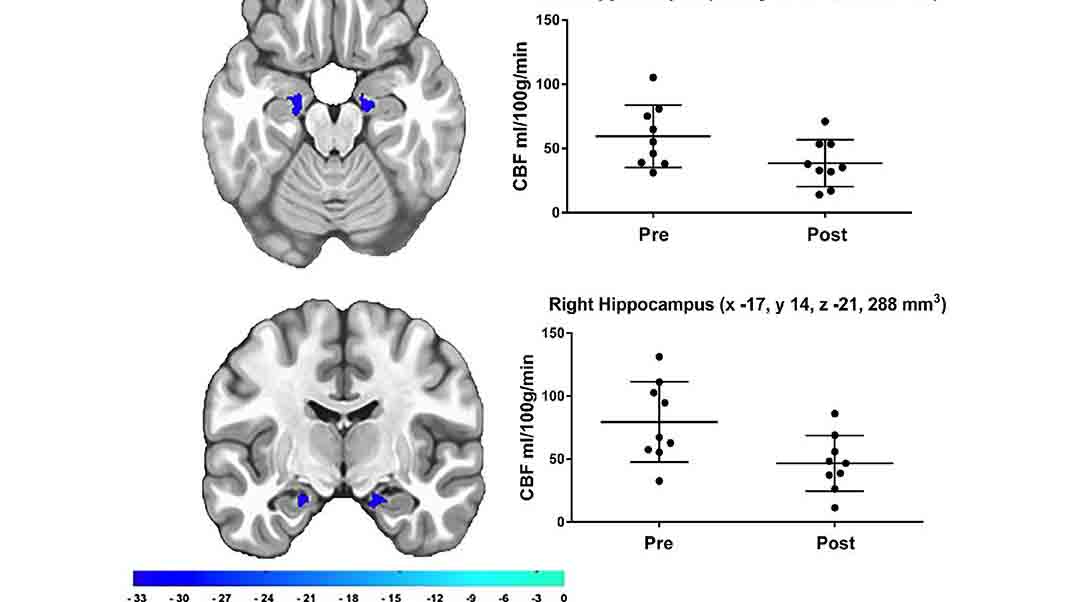

A new study says running enhances connectivity in areas of the brain associated wth high-level thinking.

A new study shows that cerebral blood flow within the left and right hippocampus significantly decreases after just 10 days of without exercise.